Originally published by Vera Files on May 27, 2019.

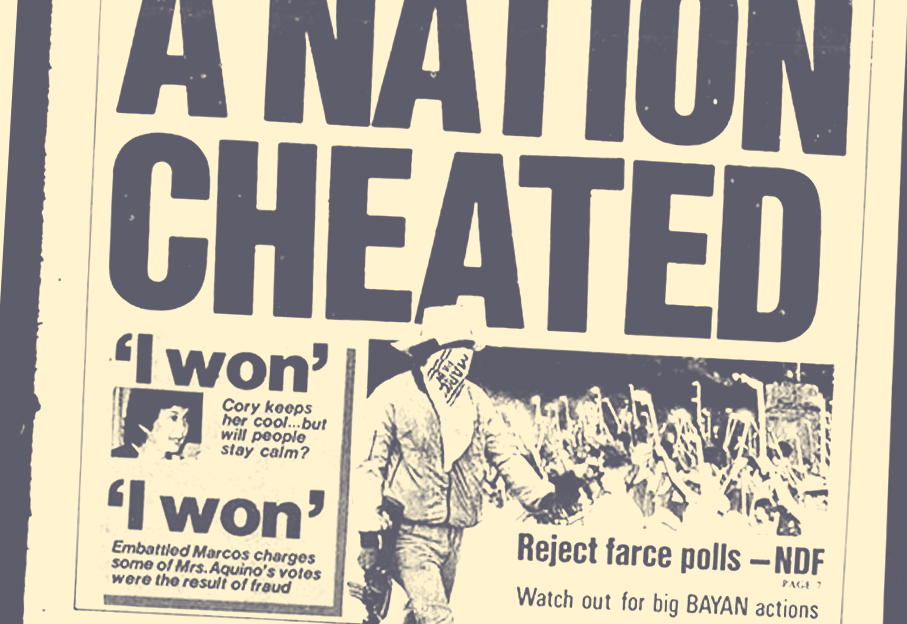

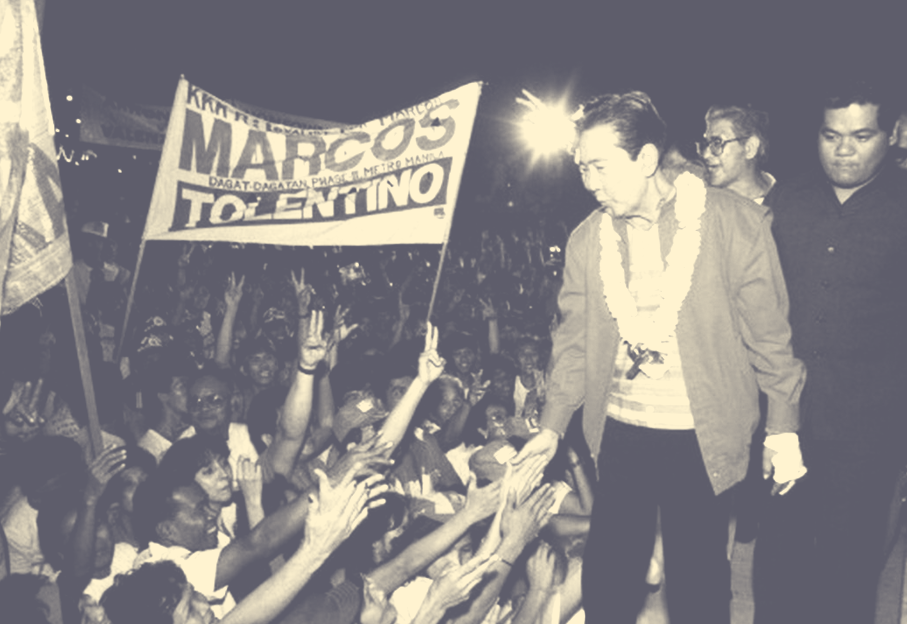

A day after the May 13 elections, the “Marcos Centennial” and “Kabataang Barangay Worldwide” accounts in Facebook became inaccessible. Prior to their decommissioning, the two Facebook pages had actively campaigned for Imee Marcos. Despite being the unapologetic eldest daughter of dictator Ferdinand Marcos and racked by controversy surrounding, among others, her false academic credentials, she garnered almost 16 million votes in a successful run for a Senate seat.

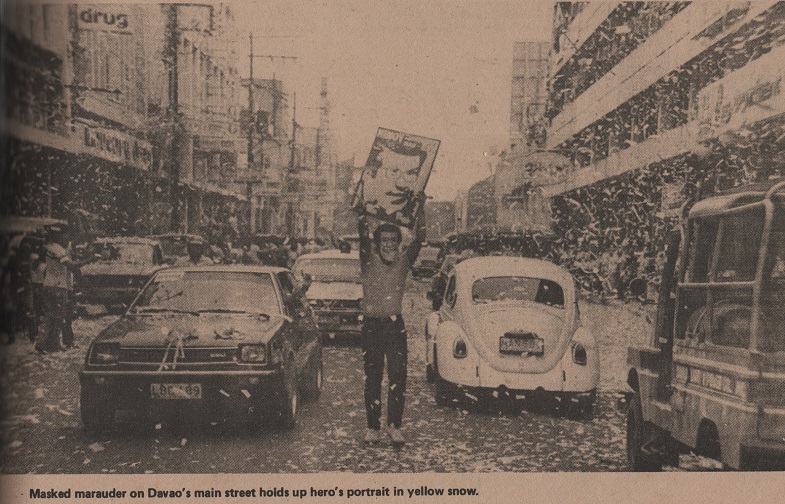

Imee’s 2019 campaign explicitly called for a Marcos Restoration: Vote for her, and she would revive the programs of the deposed dictatorship. One of her campaign ads online merely repeated words like “BLISS,” “Kadiwa,” and “nutribun,” as if to conjure a treasured past.

In contrast, the 2010 and 2016 national campaigns of Bongbong, Imee’s brother, were more focused on his claimed achievements as governor of Ilocos Norte and as senator of the republic. He had previously run for the Upper Chamber in 1995, only nine years after the People Power Revolution that ousted his father from Malacañang; then, he failed in his bid, placing 16th in the race.

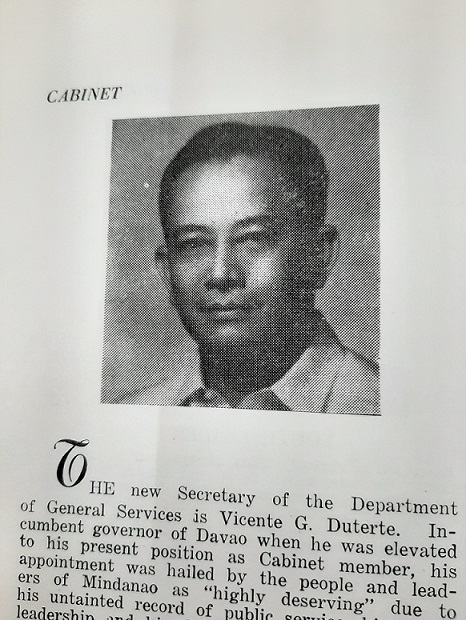

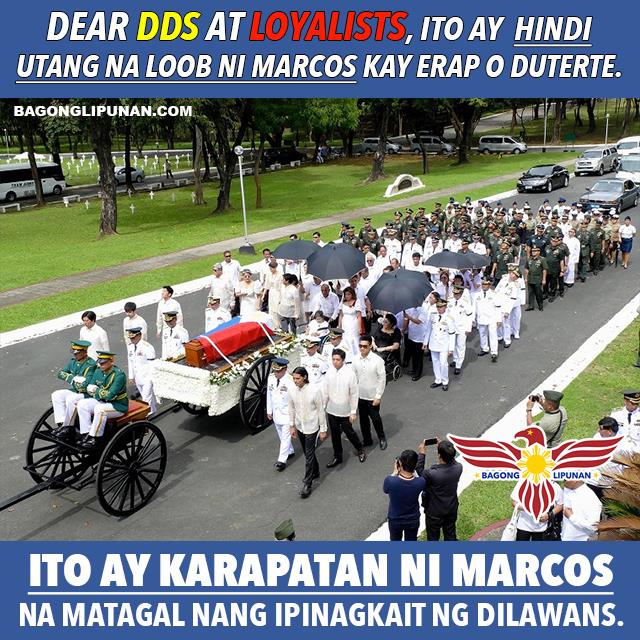

Under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, whose accommodating stance towards the Marcoses was highlighted by the burial of Ferdinand in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, Imee and her campaign handlers believed that reinforcing her ties to the Marcos regime was a winning strategy. She was the public face of the Marcos-era Kabataang Barangay, as well as head of the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines and representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte in the regular Batasang Pambansa, among other appointments and designations. Instead of downplaying her links to her father’s administration, she owned up to them. She wound up receiving the eighth-highest number of votes.

Senator-elect Imee Marcos is joined by her family including her mother, former First Lady Imelda Marcos, during her proclamation by the Comelec.

Interestingly, another online site related to the Marcoses became inaccessible late in the 2019 campaign season. The website of the Human Rights Victims Claims Board (HRVCB) (http://hrvclaimsboard.gov.ph), which contains the only complete government-recognized list of victims of human rights violations during the Marcos regime, 11,103 names in total, is currently offline. The site says: “This Account has been suspended. Contact your hosting provider for more information.”

Inquiries via email and Facebook messenger regarding the status of the site have not yet yielded any response. The HRVCB has ceased to function as mandated by Republic Act No. 10368 or the “Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013.” Enacted in February 2013, the law states that “The Board shall complete its work within two (2) years from the effectivity of the IRR promulgated by it. After such period, it shall become functus officio (of no further authority).” RA 10766 extended RA 10368’s effectivity from May 12, 2014 to May 12, 2018, while Joint Resolution No. 4, approved by President Duterte on February 22 this year, extended the availability and release of funds to the victims recognized by the HRVCB to Dec. 31, 2019. With the HRVCB closing shop, the Commission on Human Rights assumed the responsibility of distributing checks to the victims.

Even if the HRVCB has fulfilled its mandate, RA 10368 states that a roll of victims—who include those who were tortured, killed, involuntarily disappeared, or detained for exercising their civil or political rights, had their property or businesses unjustly or illegally taken over by enforcers of the estate, or were victims of such seizures “caused by” the Marcoses themselves—should have been produced by the Board, and a “compendium of (these victims’) sacrifices” should be “prepared and may be readily viewed and accessed in the internet.” The list uploaded to the site was the best approximation of an online roll of victims.

U.P. PRESIDENT DOES BALANCING ACT

RA 10368 also created the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial

Commission (HRVVMC). Its Board of Trustees is made up of heads of the

Commission on Human Rights, the National Historical Commission, the

Commission on Higher Education, the National Commission on Culture and

the Arts, the Department of Education, and the University of the

Philippines-Diliman Main Library. The CHR chairperson is the HRVVMC

chairperson.

From the U.P website

According to RA 10368, the Commission’s main responsibility is the “establishment, restoration, preservation and conservation of the Memorial/Museum/Library/Compendium in honor of the (victims of human rights violations) during the Marcos regime.” The Commission agreed to establish a Freedom Memorial Museum, which was launched on April 28, 2016, just before the presidential elections of that year. At the time, the proposed site for the museum was the grounds of the Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Nature Center. President Noynoy Aquino led the launch.

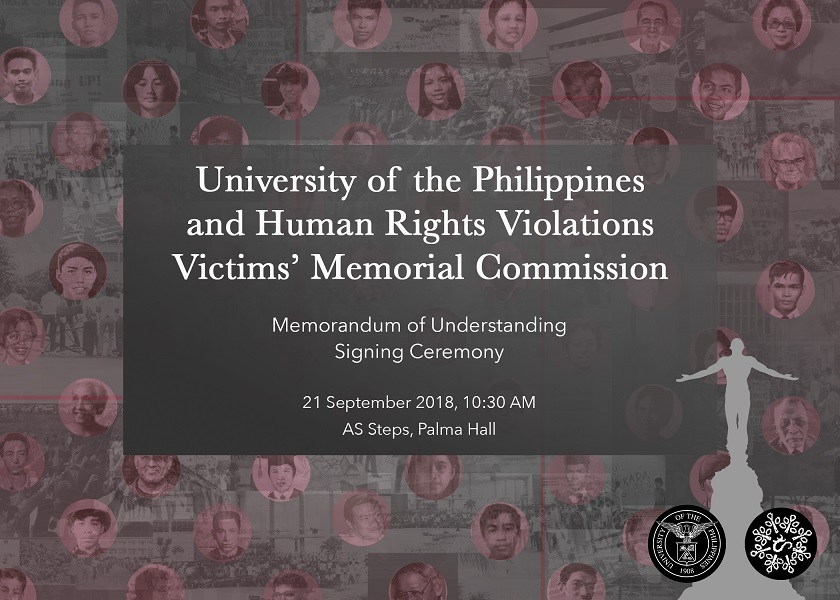

Little was heard of from the HRVVMC after President Duterte’s election. On Sept. 21, 2018, the 46th anniversary of Marcos’ declaration of martial law, members of the HRVVMC gathered at the steps of the University of the Philippines’ Palma Hall in Diliman to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the state university for the establishment of the memorial museum and/or library. A new location for the museum had been determined — a vacant lot in UP Diliman, where the experimental Automated Guideway Transit railway track once stood.

Critics consider the MoU signing to be an offshoot of the condemnation received by UP President Danilo Concepcion when he attended a Kabataang Barangay reunion with Imee Marcos at UP Diliman’s Bahay ng Alumni on August 25, 2018. Concepcion was a high-ranking member of the Kabataang Barangay and Batasan assemblyman during the Marcos regime.

Also as reported in the Philippine Collegian on June 21, 1983, Concepcion was that year’s chairman of the recognition day committee for the graduating class of the UP College of Law. He appealed to then UP President Edgardo Angara to hold recognition rites specifically for students who completed all subjects in the law school curriculum, but were not necessarily qualified to graduate with a Bachelor of Laws degree. Imee attended that ceremony despite lacking an undergraduate degree, which barred her from getting her law degree.

Photos from the Concepcion-initiated academic pageantry were circulated by Imee’s camp during the 2019 campaign period as incontrovertible proof of her earning a degree from the UP College of Law. UP had to issue a statement—twice—to say that she did not graduate from UP.

Despite Concepcion’s ties to the Marcoses, the construction of the Freedom Memorial Museum in UP Diliman is proceeding as scheduled under his watch. The museum has a website (https://www.thefreedommemorial.ph/) that details the mechanics of the Freedom Memorial Museum Design Competition. Entries were accepted from April 5, 2019, until May 15, 2019. A winner is scheduled to be announced this June.

Once constructed, the Freedom Memorial Museum will share common space with numerous structures and locations bearing names closely associated with the Marcos regime. Most prominent of these is the Cesar E.A. Virata School of Business, named after the former prime minister and Marcos’ chief technocrat. The school, formerly the College of Business Administration, was renamed in April 2013. The College of Law also houses the UP Law Class of 1987-Juan Ponce Enrile Reading Room, which bears the name of the defense minister and architect of martial law. The room was formally turned over to UP in June 2013. UP President Concepcion was then dean of the College of Law.

THE OLD NETWORK IS ACTIVE AND DELIVERING

Then there’s the money for the arts. Irene Marcos-Araneta was a known patron of Dulaang UP. But her largesse is dwarfed by that of a Marcos associate. Currently under construction is the Ignacio B. Gimenez Foundation–Kolehiyo ng Arte at Literatura Theater. The groundbreaking ceremony for the theater was held on June 13, 2013, and a cornerstone-laying ceremony was held on Dec. 14, 2016. Gimenez was in attendance during both ceremonies. At least two theaters are already named after him: the Ateneo Areté Ignacio B. Gimenez Amphitheater and the CCP Black Box Theater, formally known as the Tanghalang Ignacio Gimenez, inaugurated in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

An alumnus of UP, Gimenez, husband of Fe Roa Gimenez, former social secretary of Imelda Marcos, has served as the chairman of the Sogo Group of Hotels. He represented Sogo during its turnover of outdoor exercise equipment donated to UP Diliman in January 2015. These can currently be found at the College of Science Complex and the Department of Military Science and Tactics Complex. There is also an Ignacio B. Gimenez Award for UP Student Organization Social Innovation Projects. Gimenez was also among the first UP Gawad Oblation awardees. He was bestowed the award with 13 others—including businessman Magdaleno Albarracin, who, as recorded in the minutes of the 1288th meeting of the UP Board of Regents on June 20, 2013, “made a commitment to donate “₱40 Million as a condition to the renaming of the College of Business Administration into the Cesar E.A. Virata School of Business, after the finality of the Board’s approval on the said renaming.”

Besides setting up at least one dummy firm for the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth, according to a 2008 Supreme Court minute resolution, Gimenez was also tangentially connected to at least one other UP-related project. On June 27, 1984, Gimenez, as president of the Transnational Construction Corporation (TNCC), signed an agreement to sublease a lot in Pasay City owned by the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA). The principal lessee of the LRTA property was the Philippine General Hospital Foundation, Inc. (PGHFI). At the time, both LRTA and PGHFI were chaired by then First Lady Imelda Marcos.

LRTA agreed to lease its Pasay property to PGHFI for P102,760 a month. Gimenez’s TNCC agreed to sublease the property for P734,000 a month. The significant difference was supposed to go to UP PGH. After the EDSA Revolution, the state attempted to convict Imelda for this and related deals for violation of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. She was convicted in 1993 but was acquitted in 1998 due to technicalities. In his dissent to the 1998 decision, Justice Artemio Panganiban noted that “(other) than her out-of-court utterances, petitioner has submitted no evidence whatsoever to indicate that the money gained by PGHFI from TNCC (and lost by the LRTA) was actually spent for a hospital or any other charitable purpose.” A director of the PGH interviewed by journalist Raissa Robles in the early 1990s told her that “PGH never got a centavo” from PGHFI.

THE REHABILITATION OF THE MARCOS NAME

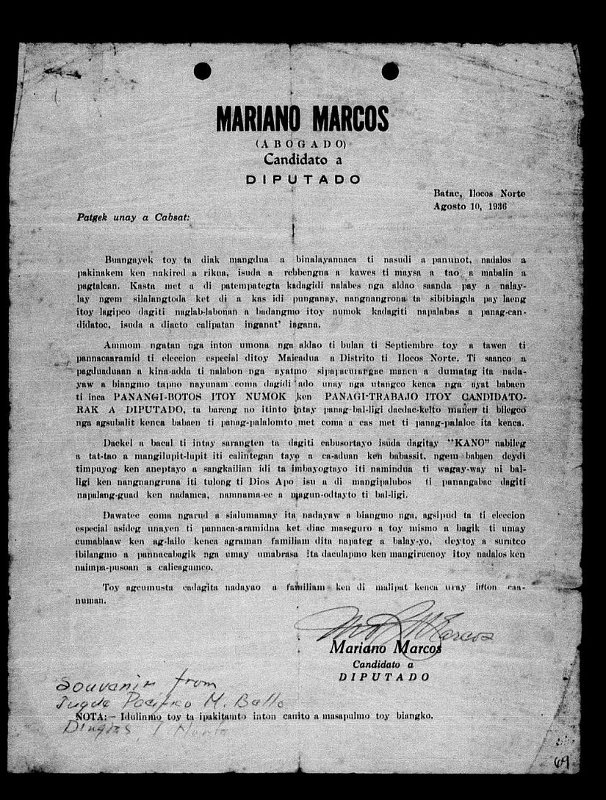

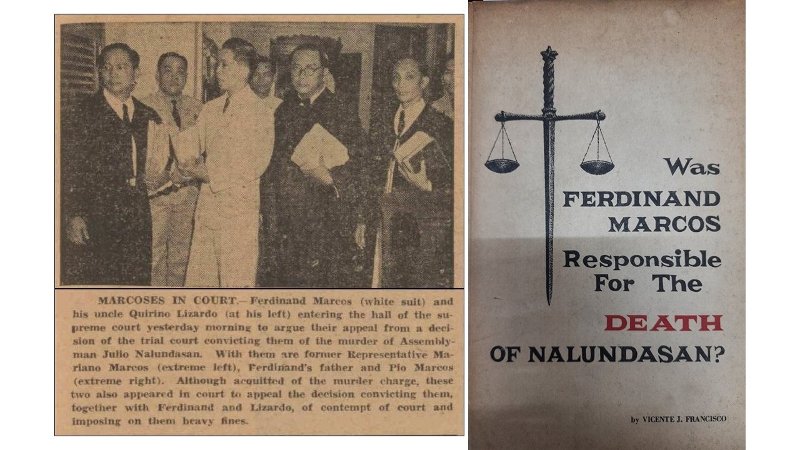

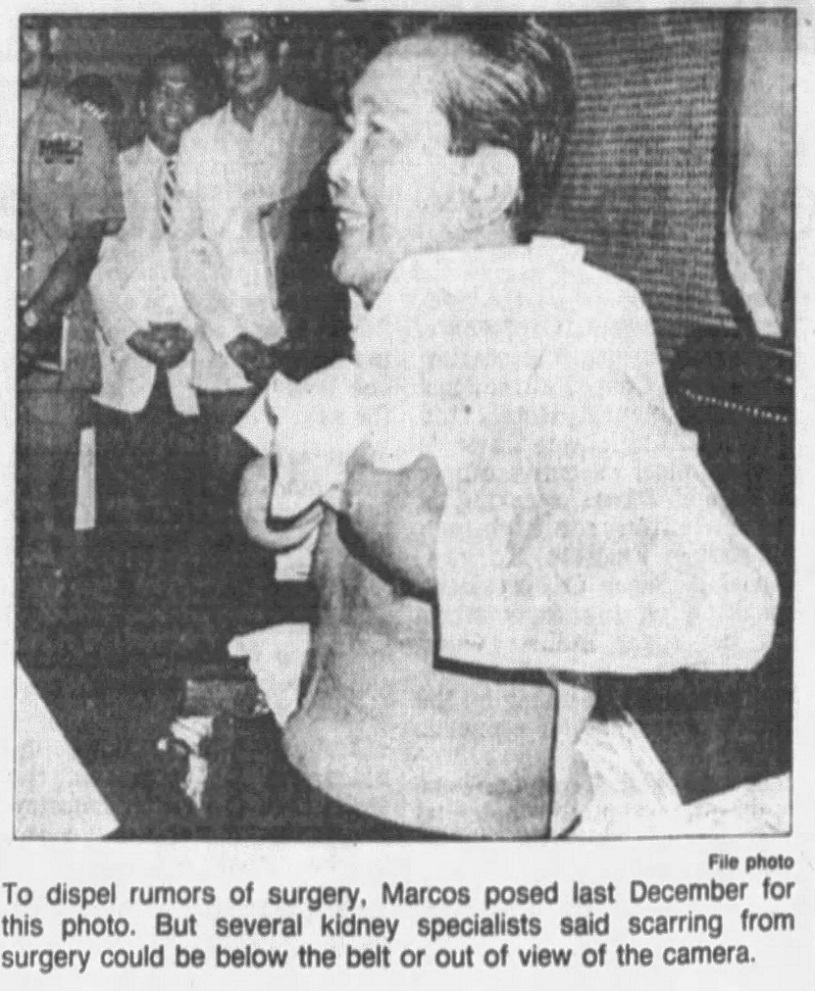

Since their return to Philippine politics in 1992, only six years after Ferdinand Marcos was deposed, the Marcoses have been spearheading attempts to rehabilitate their patriarch’s rule. As is now clear, it was borne out of their need for political survival than out of filial duty.

From the Bagong Lipunan Facebook Page

In 1992, Bongbong, as the representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte, filed House Resolution No. 80 calling for the return of Ferdinand’s remains from exile in Hawaii and according his father a state funeral “befitting a former president of the Republic.” Less than half of the House co-authored the resolution, which was consigned to the House archives in 1994. In March 1993, Bongbong filed House Bill No. 8363, which aimed to rename the Mariano Marcos State University in Batac to the Ferdinand E. Marcos State University. The bill died at the Committee on Education and Culture that same year.

Imee, in contrast, left such lionization attempts outside of her legislative agenda. In her 2012 Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth, Imee is listed as the officer-president of the Marcos Presidential Center, Inc. since January 16, 2002. Among the Center’s projects were: a website (www.marcospresidentialcenter.com, launched in 2002, now defunct); the publication of books that highlighted the achievements of Ferdinand, initiated in 2007; the renovation of the Ferdinand E. Marcos Presidential Center in Batac, Ilocos Norte; and the drafting of public relations pieces. The Center provided the text and photos for a press release, used as a basis for articles published in various media outlets, regarding the November 2017 marriage of Michael Marcos Manotoc, Imee’s son, to Carina Manglapus, granddaughter of former senator Raul Manglapus. The piece characterized the marriage as a reconciliation of rival political families from Ilocos.

In one of his papers, film scholar Joel David mentioned an informal interview with then-representative Imee, who “expressed her plan to popularize what she called ‘Marcos studies.’” On Sept. 16, 2002, the Manila Standard printed an article by Imee titled “Revisiting Martial Law.” There, she stated that the “time has come to study intently, intensely, dispassionately, completely, the Marcos era, before, during and following the Martial Law period, applying intellectual rigor over emotion, scholarship, not partisanship.”

Manuel Alba, once Marcos’s budget minister, was interviewed twice by Professors Teresa Encarnacion Tadem, Cayetano Paderanga, and Yutaka Katayama for their oral history project, “Economic Policymaking and the Philippine Development Experience, 1960-1985.” In one of the interviews, held in January 2009, Alba mentioned that Imee had a “Pamana project,” which intended to “document the Marcos’ achievements,” for which he committed to “write on budget and education.” Alba also revealed that Onofre D. Corpuz, one of Marcos’s education ministers and former UP president, was going to write a “framework” for the project. It is unknown if there was any further progress on the project before Corpuz’s death in 2013.

In a lengthy interview by Jojo Silvestre, published on the website of the Philippine Star on Nov. 21, 2010, Imee complimented Alba along with many other members of the Marcos cabinet, calling him brilliant. In the same interview, Silvestre noted that “Cabinet meetings must have been a free-for-all.” Imee revealed intimate knowledge of such meetings, as if she had attended some, though she was not known to have held any Cabinet-level position during her father’s rule. When asked about martial law, Imee told Silvestre, “I don’t see myself as an apologist. Sa haba ng panahon, you have to judge it in context, in its time … (The) other side of the story is very well documented. And even over-documented.”

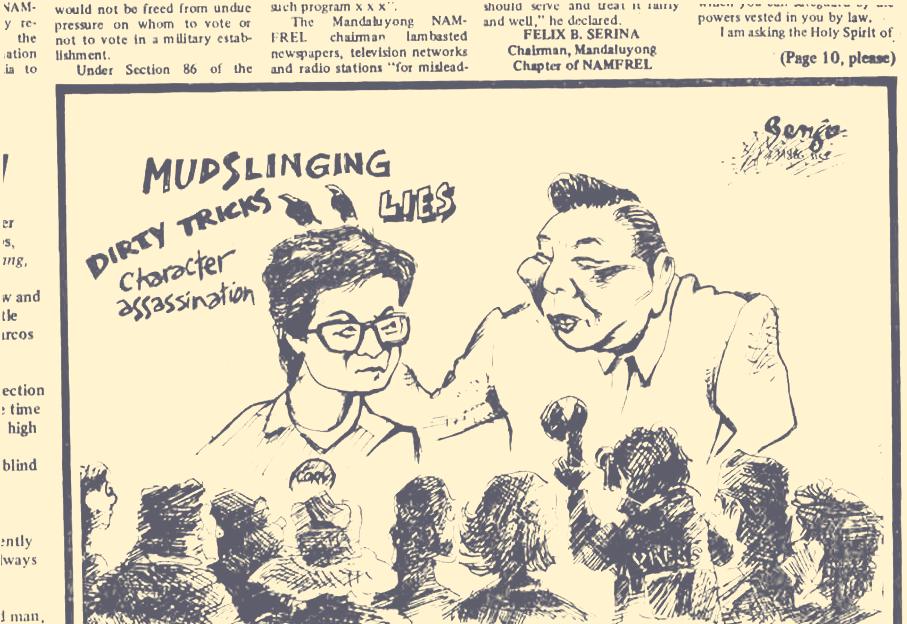

IMEE MORE FOCUSED IN RESTORING MARCOS NAME IN HISTORY

During the 2019 campaign, Imee seemed unwilling to engage on the issue of her family’s ill-gotten wealth and the abuses committed during the Marcos regime. When asked about the recent Sandiganbayan decision convicting her mother Imelda of seven counts of graft, Imee would cite the sub judice rule barring public disclosure of details of pending court proceedings. The rule does not apply to the cases on the Marcos’s ill-gotten wealth that have been decided with finality, though she denied that any existed when she filed her certificate of candidacy on Oct. 15, 2018.Earlier, during the 2018 anniversary of the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, she was quoted by the Philippine Daily Inquirer as saying “(the) millennials have moved on, and I think people at my age should move on as well.”

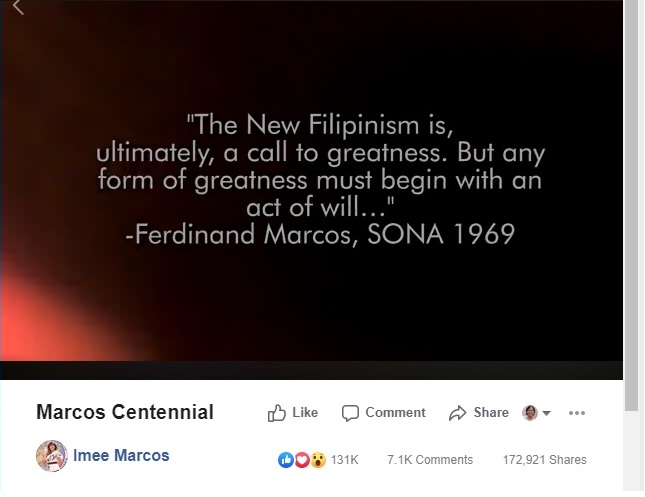

Propagating Ferdinand Marcos’ statements. From Imee Marcos Facebook Page.

She made a similar statement almost 20 years ago. On Dec. 12, 1999, the Associated Press quoted her as saying, “Many of the younger people who don’t have so many preconceived notions, actually received a lifetime virtually of propaganda, are beginning to think that it is important to review what actually happened.”

Under current political conditions, Imee may succeed where brother Bongbong failed. The votes that secured for Imee a Senate seat were not just a product of nostalgia for an authoritarian past or merely a reflection of first-time voters’ ignorance of the brutality and excesses of the Marcos regime. They were also, in part, paid for by long-time allies and cronies of the Marcoses who, in the process of buying respectability from academic institutions, also contributed to the cause of burnishing and enthroning the Marcos name in Philippine history and politics.

The increasingly favorable political fortunes of the Marcoses and their cabal may also mean the effective erasure of memories of both human rights violations and compromises with those who obtained their wealth through plunder or abuse of authority, signaling that if the Marcoses could get away with such abuses, so can others. If the record of the human rights victims of the past can disappear, so, too, can the record of the comparable brutalities of the current dispensation. One bloody bejeweled hand washes the other.