Originally published by Vera Files on November 27, 2020.

On November 9, 2020, between two destructive typhoons and amid a raging pandemic, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. filed a motion for inhibition against Supreme Court Associate Justice Marvic Leonen, who is tasked with writing the decision on Marcos’ poll protest against Vice President Leni Robredo.

Former senator Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.files a motion for the immediate inhibition of Associate Justice Marvic Leonen from his electoral protest, Nov. 9 2020. Photo from Bongbong Marcos FB page.

Leonen was biased against his family, claimed Marcos, whose petition was seconded by an allegedly unrelated one filed on the same day by Solicitor General Jose Calida, a known Marcos supporter. The Supreme Court, sitting as the Presidential Electoral Tribunal, disagreed, junking both petitions eight days after they were filed.

Marcos started to claim that he was being cheated even before the 2016 race for the vice presidency was officially called. It was only Bongbong’s second electoral loss; he handily won whenever he ran for executive or legislative positions in Ilocos Norte, for decades a Marcos bailiwick. He placed seventh in the 2010 senate election, giving him his first and thus far only national position.

His 1995 senate run was far less successful. He placed in the bottom (losing) half of a thirty-person race. The winning circle was dominated by candidates of the Fidel Ramos administration’s Lakas-Laban coalition, including Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, the election’s topnotcher. Nikki Coseteng, Gringo Honasan, and Miriam Defensor Santiago were the only opposition candidates who won seats in the Senate.

Honasan and Santiago supported Bongbong’s claim that the 1995 polls were tainted with “widespread fraud and trending,” as reported by the Manila Standard on May 9, 1995, the day after the elections. The article quoted Marcos as claiming in a press conference that a “highly placed cabal has been orchestrating a bogus quick count and propagating election results based only on tallies favorable to the administration candidates.” He reportedly said there would be “social unrest” if the Ramos administration “succeeds in defrauding the electorate and frustrating the will of the people.” Marcos formally asked the Commission on Elections to stop what he called an “unauthorized and unofficial quick count.” The same article quoted the administration coalition’s spokesman Ruben Torres, who thought that “young Marcos was seeing ‘ghosts’ of his father’s election machinery,” and who noted that pre-election surveys showed Bongbong was never a popular choice of the electorate at the time.

As reported on May 20, 1995 by the Standard, Marcos later asked for a suspension of the official Comelec canvass, citing irregularities such as “point shaving,” incorrect tabulations, and vote buying. He claimed to have lost many votes to two candidates in particular: topnotcher Macapagal-Arroyo and third placer Ramon Magsaysay, Jr., and that the cheating was within the precinct and provincial levels. The report said Bongbong “insisted that ‘two or three people’ were involved in the conspiracy to ease him out of the winners circle [but] he could not name them at [that] point as his group was still gathering evidence.” By then, only six out of 98 certificates of canvass had yet to be tallied, and Marcos was in 16th place.

Nothing came of Bongbong’s complaints, and the unrest he foresaw did not materialize. He was elected Ilocos Norte governor in 1998, a position he held for nine years.

Bongbong was not the first Marcos to cry fraud after losing an election for the first time under the 1987 Constitution. Imelda, his mother, was confident that she would win the seven-way race for the presidency in 1992. When it became evident that she would become an also-ran after the counting of votes was under way, she cried fraud. As reported by the Standard on May 17, 1992, Imelda held a press conference at the Philippine Plaza Hotel, during which she alleged “systematic and widespread cheating in the Philippine presidential elections” and that she planned to “boycott all court proceedings against her” as a form of “personal civil disobedience.”

A Reuters article published on May 16, 1992 in American and Canadian newspapers quoted Imelda as also saying: “Deep in our hearts we know we won, although subsequent events indicate that many of the ballots were not credited to me.” About a month later, an Associated Press story carried by various American papers reported that Imelda finally conceded and “threw her support behind the front-runner,” Fidel Ramos.

A few years later, she won her first post-EDSA Revolution position. According to a Reuters article that came out in the Standard on May 13, 1995, when Imelda was on the cusp of officially winning as representative of the first district of Leyte, her home province, she reportedly declared, “We received an overwhelming, undeniable majority. We won.” But, with her son’s chances of becoming senator at the time growing slimmer by the day, she also stated, “There are those who will stop at nothing to keep the people from electing the Marcoses.”

Interestingly, there have been times when the Marcoses claimed outright that elections in the country were tainted with fraud—committed by people on their opponents’ side and, by their own admission, their own—but they accepted the results without contest because the results were seemingly in their favor.

In January 1978, President Ferdinand Marcos announced that an election for the members of an Interim Batasang Pambansa, or IBP would be held in April that year. The election for the IBP’s regional representatives was held on April 7, 1978. Marcos’ Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) coalition won the overwhelming majority of IBP seats. The opposition coalition Lakas ng Bayan (later the “Laban” in PDP-Laban), whose leadership included the then-detained Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino, Jr., did not win a post, even after their decision to contest only the twenty-one seats available in Metro Manila.

That votes were cast for opposition candidates, however, bothered Marcos. As the ballots were being tallied, he ordered a survey “to determine why votes were cast against the administration,” according to an Associated Press article. In the same news conference, Marcos claimed that electoral fraud “was done on both sides,” adding, however, that such fraud was “on a small scale and certainly not on a scale to affect the election.” The same AP article said Marcos critic Jovito Salonga disagreed with this assessment, noting that people did not visibly celebrate KBL’s victory because they felt “like they’ve been cheated.”

After the 1978 elections, Marcos became “President-Prime Minister” until 1981, the year he lifted martial law, but retained his power to issue decrees. That year, Marcos was elected to serve as president with a six-year term, in accordance with the amended 1973 Constitution. The opposition boycotted the polls.

Another election, this time for members of the Regular Batasang Pambansa, was held in 1984. Again, KBL became the majority party, though the opposition, strengthened in no small measure by Ninoy Aquino’s assassination the year before, won a third of the available seats. Among the winning candidates was Imee Marcos, the president’s daughter, elected representative of Ilocos Norte’s second district. She held that seat until the EDSA Revolution.

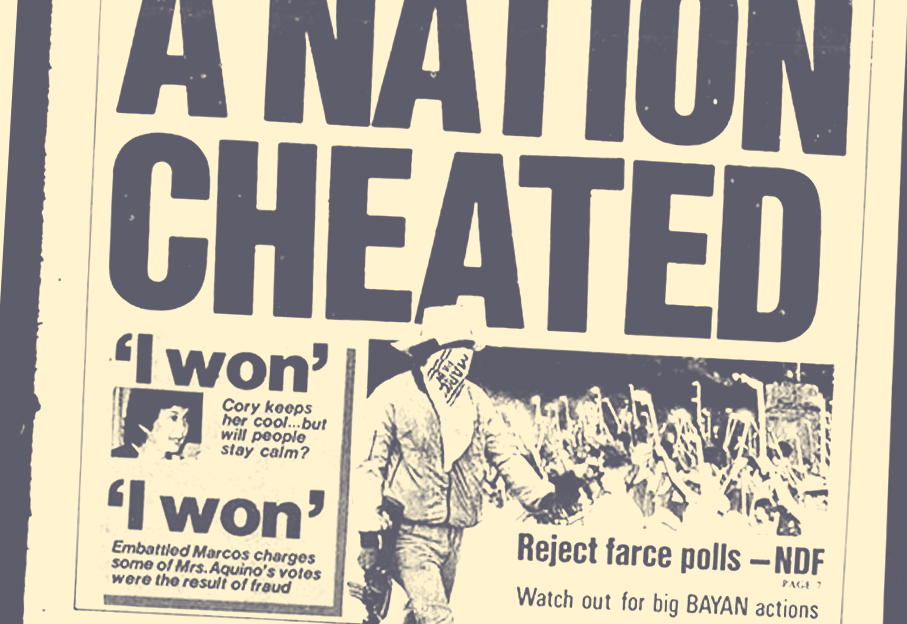

Days before her father’s ouster, member of parliament Imee claimed that “there was fraud on both sides” during the 1986 snap presidential election, of which the Comelec declared Marcos the winner against Corazon Aquino. (The count by the Comelec-accredited monitor, the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections, said otherwise). Imee said this while still insisting to the Straits Times in Singapore that the election was a “clean and relatively peaceful one.” She said fraud occurred “because [the] election was such an emotion-charged and keenly contested one,” but that “only fraud on the part of the administration was given full media treatment.”

Imee’s father echoed her statements over a year later in an interview he and Imelda gave to Playboy while they were in exile in Hawaii. The August 1987 U.S. issue of Playboy quoted Marcos as saying: “There was fraud on both sides. But mine was not massive.”

However, Marcos and his subordinates had, by then, been linked to significant electoral fraud. In a press conference on February 22, 1986, at the height of the EDSA revolt, then Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile admitted that, in his own region, he knew “that we cheated the elections to the extent of 350,000 votes.” This was preceded by the famous quick count walkout on February 9, 1986 of 35 Comelec programmers, whose tallies of reported returns did not match what was displayed on the tally boards being broadcast on national television.

As reported by Seth Mydans of the New York Times on February 10, 1986, a delegation of 44 election observers from 19 countries noted that “electoral anomalies which we have witnessed are serious and could well have an impact upon the final result,” and that these anomalies included “vote-buying, intimidation and lack of respect for electoral procedures.” According to Mydans, the observers “had seen no instances of fraud committed by Mrs. Aquino’s supporters.”

Ferdinand always claimed that he won legitimately. In a press conference in Malacanang on February 11, 1986, he parried a claim made by a foreign journalist that the closeness of the vote showed that he was, in fact, losing his mandate.

“Voters that supported me are the poorer classes of our people, and those are the people who will do the fighting against the communists,” he said. “It’s not the elite, the elite that seems to have supported my opponent.”

It was widely reported, in articles of the Associated Press and the New York Times, that on the eve of the elections, bags of rice, marked “Gift From the President,” were being handed out by Marcos supporters. On the same day, according to the AP, “Pro-Marcos newspapers ran full-page announcements that said the government food market was offering big discounts on items ranging from ketchup to laundry soap.”

Less well-known today are the reported shenanigans during the 1978 IBP elections. Reuben Canoy, in his book The Counterfeit Revolution, mentioned, among others, a claim that during the 1978 polls, Las Piñas mayor and Marcos loyalist Filemon Aguilar’s men pointed their guns at the LABAN poll watchers in his territory and sent them home. The Citizens’ Report on the First Election Under Martial Law in the Philippines by the Ecumenical Crusade for a Conscienticized Electorate detailed claims that both LABAN and Kilusang Bagong Lipunan watchers were kept from entering precincts in Las Piñas, and that after the polls closed at 5:00 PM, Aguilar himself stuffed the ballot boxes with prepared ballots for Marcos’ KBL.

Despite such alleged irregularities, according to Agence-France Presse, on April 8, 1978, a day after the election, Marcos had announced “a clean government sweep in the parliamentary elections in Manila and a swift crackdown if violent opposition protest demonstrations should occur.” Comelec had not even finished their official canvass by then. So intent was he in securing a win and projecting at home and abroad that the opposition had little to no influence.

Regardless of the outcome of Bongbong’s poll protest, he will likely still have the support of entrenched political dynasties with members in the highest tier of the Philippine political hierarchy—including the Dutertes and the Aguilars, among whom are Filemon’s daughter, Senator Cynthia Aguilar Villar—come 2022, when Bongbong says he will run for another national position. But will such support translate to a resounding electoral victory if Marcos’ loss to Robredo is confirmed with finality?

The sizable Marcos loyalist forces will not care. They believe that Ferdinand Marcos legitimately won all elections held while he was president, including the 1986 snap election. They joined Imelda’s protests in 1992 and Bongbong’s complaint in 1995. They echo on social media whatever the Marcoses say about his ongoing electoral protest, including claims about Justice Leonen. They find a Marcos loss unimaginable—all other evidence to the contrary.

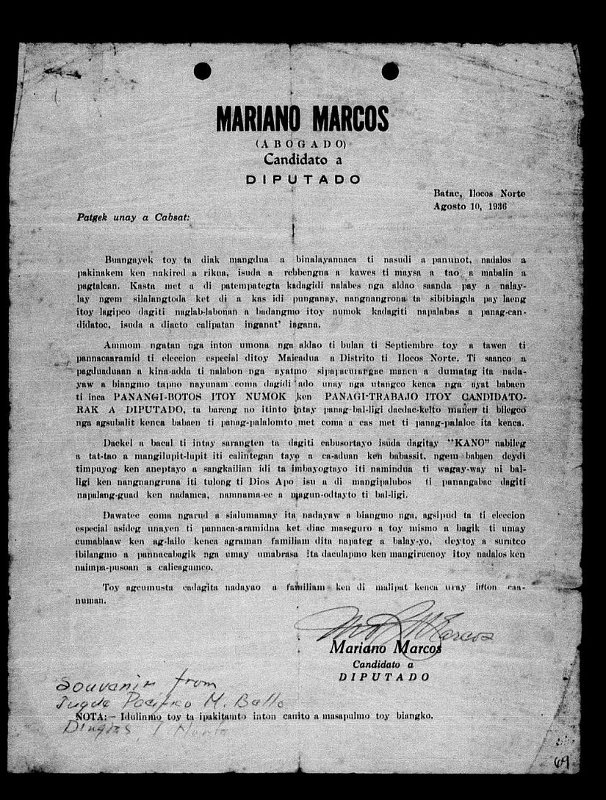

Campaign letter of Mariano Marcos, 1936 (In Ilocano) (from the digitized PCGG files)

Indeed, before Ferdinand Marcos launched his political career in 1949, his father Mariano Marcos was known for losing in elections—badly. Mariano was twice elected representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte in the pre-Commonwealth House of Representatives, but lost a bid for a third term to Emilio Medina. In 1934, Mariano tried to win back the congressional seat, but lost to Julio Nalundasan. In 1935, Mariano and Nalundasan ran against each other to be the representative of Ilocos Norte’s second district in the Commonwealth-era National Assembly. Again, Nalundasan won, handing Mariano a third successive electoral loss. Nalundasan was murdered days after winning, and another election was held in 1936 to determine the successor. Mariano lost a fourth time; the winner, Ulpiano Arzadon, won by a landslide—over 7,400 votes to Mariano’s 2,507.

According to Arzadon in an article published in the Tribune on September 13, 1936, nearly two months after he was elected, certain accusations made by Mariano against him that were published in Manila dailies “constitute a series of insults to the electorate” of Ilocos Norte. Arzadon said that his “decisive triumph in each and every municipality within the second district of Ilocos Norte,” including Marcos’ home town, “is an unequivocal expression of the will of my province that Mr. Marcos has completely been repudiated by the electorate.”

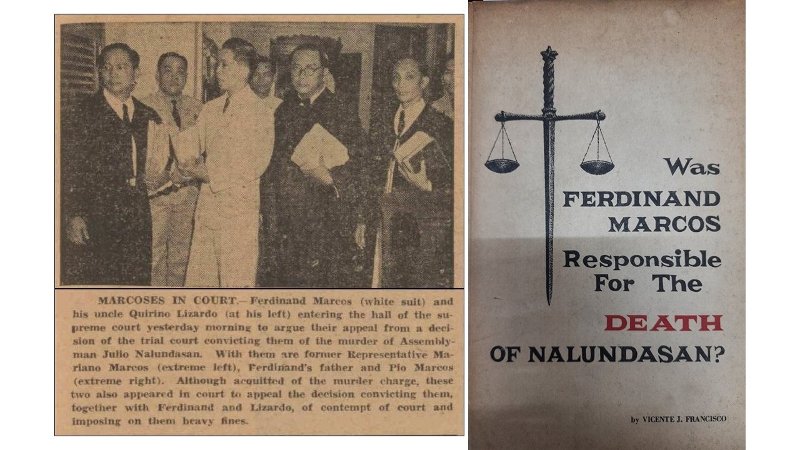

Mariano did not run in the 1938 elections, the year he and three of his relatives, including his son Ferdinand, became prime suspects in Nalundasan’s murder. All were eventually acquitted upon appeal, although Ferdinand would keep fending off accusations of involvement.

Left, Marcoses in court, 1940. From the Sunday Tribune, 13 October 1940 (downloaded from Trove/National Library of Australia). Right, cover of “Was Ferdinand Marcos Responsible for the Death of Nalundasan?” book published in time for the 1965 elections, written by Marcos’s lawyer, Vicente Francisco (Third World Studies file)

According to guerilla leader Jose Llanes, in the May 14, 1945 supplement to his May 3, 1945 Report on Ilocos Norte to the Secretary of the Interior, “Ilocos Norte has always been in political turmoil before the outbreak of the [Second World War]. Politicians there kill one another, e.g. the unsolved murder of the late Rep. Julio Nalundasan. Political elections are characterized by defamations and mud-slinging.” Llanes added: “Men involved in such gains do not hesitate to resort to any means to achieve political ends, even murder, as shown in the murder of Rep. Nalundasan. One better proof is the collaboration of political lame ducks.” Among these collaborators, Llanes labeled Mariano Marcos as a “pro-Jap spy.” Ferdinand would insist after the war that Mariano in fact defied the Japanese and was killed by them.

The roundly rejected candidate Mariano now has a university with a sprawling campus named after him in his hometown in Batac, Ilocos Norte, thanks to his son Ferdinand, who decreed the creation of the Mariano Marcos State University on January 6, 1978. Many more streets and institutions were named after Mariano during his son’s rule, as if to ensure that Mariano’s previous ignominy would be buried under steel and concrete.

One wonders if Bongbong’s insistence that he won the vice presidency is intended to help ensure that he could someday do for Ferdinand what Ferdinand did for Mariano.