Originally published by Vera Files on September 29, 2019.

VICENTE AND FERDINAND

Sino sa inyo ang nagsuporta sa akin? Ilan lang? Sino? One or two. Ilan lang? Four, five six? Wala akong barangay captain, wala akong congressman, wala akong pera. Si Imee [Marcos] pa ang nagbigay. Sabi niya inutang daw niya. Si Imee supported me.

Pres. Rodrigo Duterte

Oct. 4, 2016

These statements by President Rodrigo Duterte, made during a meeting with local

officials of Luzon at the Dusit Thani Hotel in Makati City on October 4, 2016, are puzzling. For one, Duterte seems to have forgotten that one of the earliest “Duterte for President” groups was launched by barangay captains from Davao City in October 2014. For another, as reported by various media outlets, Imee Marcos is not listed in Duterte’s Statement of Contributions and Expenditures. However, as pointed out by Vera Files, the biggest contributor to Duterte’s campaign was Antonio “Tonyboy” Floirendo Jr., who was “among the prime movers of the Alyansa ng Mga Duterte at Bongbong (ALDUB), a

group that campaigned for a Duterte-Bongbong Marcos tandem.”

Antonio Sr., Floirendo’s father, was a known Marcos crony. He was chairman of the

Marcos administration party Kilusang Bagong Lipunan in the Davao Region, a position that, based on other files in the custody of the Presidential Commission on Good Government, he used to lobby for appointments of local officials in his domain.

Antonio Floirendo Sr. with Ferdinand Marcos, from Notes on the New Society II: The

Rebellion of the Poor by Ferdinand Marcos, 1976

Are there any available documents or accounts showing the Dutertes and the Marcoses

had a very close personal relationship prior to the leadup to the 2016 elections? In an academic workshop last year, a former journalist claimed that he had never known Duterte to praise Marcos when he was mayor of Davao City in the 1990s. What do we really know

about the purported ties of these political families?

There is adequate evidence to show that the political fortunes of the Dutertes have

been intimately tied with those of the Marcoses for decades, but insufficient evidence to show that the former were loyal to Ferdinand Marcos well before he became president. Among the few who seem to have the authority to claim the contrary is President Duterte. In his above-quoted October 2016 address, Duterte also said:

“I do not know if because you know my father was a Cabinet member of President

Marcos during the first term of his presidency. My father was one of the two who stood by Marcos in his darkest hours. Everybody was shifting to the Liberal at that time, kay Diosdado Macapagal. And it was only [Zamboanga del Sur Governor Bienvenido] Ebarle and my father who stood by Marcos.”

Again, the president’s meandering way of speaking aside, those claims are

confusing, given the facts of Philippine political history.

Vicente Duterte. from the 1967 Philippine Officials Review

Then Senate President Ferdinand Marcos defected to the Nacionalista Party in

1964, after it became clear that President Diosdado Macapagal would not honor the well-documented promise he had made to let Marcos be the standard bearer of the Liberal Party in 1965. There were, indeed, defections from NP to LP between 1964 and 1965, but the switching at that time did not result in only two incumbent governors from

Mindanao staying with the NP. The mass switching that led to that happened earlier, within the first year of the Macapagal administration, a development in keeping with the political

traditions practiced in the Philippines until today.

Was Vicente Duterte ever strongly identified with Ferdinand Marcos, who appointed

him Secretary of General Services on December 30, 1965? Tom Sykes, in his 2018 book The Realm of the Punisher: Travels in Duterte’s Philippines, writes: “Vicente didn’t take to national politics [after his appointment as General Services secretary] and soon went

back to practicing law in Davao. On 21 February 1968, he collapsed in court from heart failure and died.” Sykes’ information on Vicente’s date and manner of death appear to be correct. However, Vicente did not leave Marcos’ cabinet simply to return to private

practice.

In June 1967, President Marcos signed Republic Act No. 4867, splitting the undivided Province of Davao into Davao del Norte, Davao del Sur, and Davao Oriental. An election was held on November 14 of the same year for the representatives of Davao del Sur and Davao Oriental, coinciding with the 1967 midterm election. Vicente ran against two

other Nacionalistas for the congressional seat of Davao del Sur. Artemio Al. Loyola, the official Nacionalista candidate and long-time member of the Davao Press Club, won; Vicente, who was still a member of the NP but ran as an independent, trailed the winner by over 8,000 votes.

The loss—his first and only—must have been devastating to Vicente. Four years earlier, he won his second elected term as governor of the Province of Davao, beating two LP candidates.

But if Vicente had enjoyed Marcos’ support, why was he not an official NP candidate in 1967? If the account of Rodrigo’s sister Eleanor “Baby” Duterte, in the I-Witness documentary “People Power sa Davao” is to be believed, Vicente actually did not leave Marcos’ cabinet in the best of terms. According to Eleanor, her father was fed up with the corruption he had witnessed in Malacañang under Marcos.

But Marcos must have trusted Vicente, who as Secretary of General Services would have

had to deal with government suppliers and contractors constantly as well as sensitive communications that went through his department. Vicente’s association with Davao may have also played a role in the decision to bring him to Malacañang. The first two who occupied that position before Vicente came from Mindanao, and the appointment arguably had been seen as one for Mindanawon politicians. Vicente’s replacement was Salih Ututalam from Sulu.

But even with the power and trust he was given, was Vicente ever personally loyal to

Marcos? In his profile in the 1967 Philippine Officials Review, Vicente is described thusly:

During his incumbency as Davao governor, he was once cited as one of the

“Outstanding Governors” of the Philippines. Twice offered study-travel grants to observe the progress of community development in Thailand and Israel, he declined both as a matter of conviction and principle for he was then in the opposition party. At the height

of the Liberal Party power, it was his distinction to be the only Nacionalista governor in Mindanao who did not change party affiliation for personal, political convenience or even in the face of presidential pressure.

Based on this, it can be surmised that the loyalty President Duterte was alluding to in

October 2016 was not tantamount to allegiance to Marcos, who was still a Liberal when that party was dominant. Vicente was, unlike his many flip-flopping compatriots, a true Nacionalista stalwart, who, either because of his own political ambitions or because he did not see eye to eye with his party’s turncoat leader, decided to return from Malacañang to Davao, where he probably thought that he was still, according to his 1967 profile, seen as someone who “rendered personalized service to his constituents” and had “humble, modest and unassuming self-qualities” that “endeared him to his legion of friends and admirers.”

While campaigning in Batac, Ilocos Norte in February 2016, Rodrigo was quoted as

saying, “Speaking of loyalty and friendship, I am proud to say that my father was a close ally of President Marcos until his death.” Why did Rodrigo decide to package Vicente as a true-blue Marcos loyalist, despite evidence to the contrary? Were the votes of those who love the Marcoses worth bending the truth about Vicente?

THE YELLOW-LOYALIST-LEFTIST CANDIDATE

Davao City was where Rodrigo Duterte cut his teeth as a politician, seeing up close conflicts ranging from squabbles in the local judiciary to bloody urban warfare to the movements that led to the overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship.

His involvement in the last one has not been extensively discussed. Various sources note that he was identified with anti-Marcos forces because he is the son of Soledad “Soling” Duterte, a known leader of the opposition in Mindanao.

Soledad Duterte, Mr. & Ms. January 6, 1984

In 1977, according to historian Macario Tiu in the book Davao: Reconstructing

History from Text and Memory, church leaders in Davao “dared [to] initiate open protest actions” against the Marcos regime. The protests gradually intensified and became much more frequent after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in August 1983. Soon after, there

sprung what was called the United Opposition of Region XI. According to Tiu, among the leaders of organizations forming the alliance was Soling Duterte of Kalikuhan alang sa Tawhanong Kagawasan, or KATAWHAN.

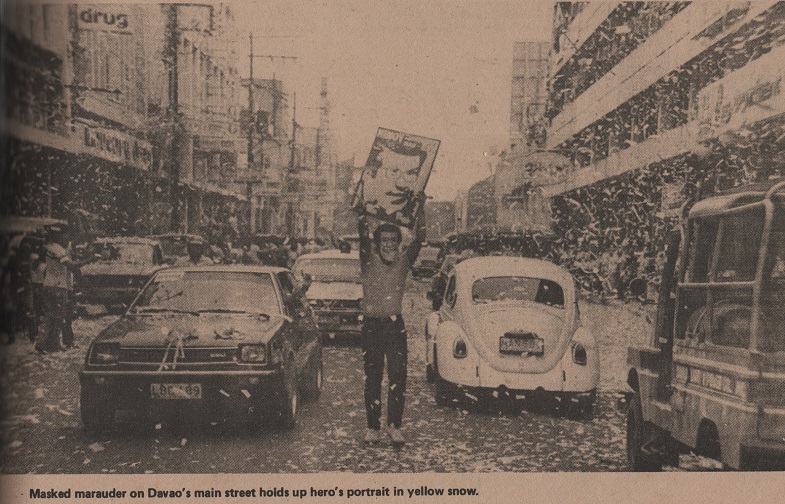

Ana Maria Clamor, in the monograph entitled NGO and PO Electoral Experiences: Documentation and Analysis, notes a major activity of this alliance was the almost weekly non-violent “Yellow Friday” marches in Davao City’s major thoroughfares, which “drew inspiration from the yellow confetti rallies in Makati.”

After the dust of the EDSA Revolution settled, President Corazon Aquino appointed

Zafiro Respicio officer-in-charge of Davao City. Soling Duterte’s son, Rodrigo, was appointed OIC vice mayor. There are sources who say that, at the time, Rodrigo was a logical choice for the position, even though he was a member of the Marcos-era bureaucracy.

Clamor, writing in 1993, says that Rodrigo was “one of the few city fiscals who actively supported the Cory-Doy [Laurel] ticket and joined the February 1986 revolution.” Adrian Chen, citing Luz Ilagan, in an article published in November 2016 for the New Yorker, wrote that “Duterte was able to help dissidents without compromising his position in the government” by ensuring that activists arrested in Davao City were not abused while under custody.

Davao-based journalist-turned-academic Jose Jowel Canuday, in an interview published in the September 2016-March 2017 issue of Social Transformations: Journal of the Global South, recalled that Rodrigo was always in the “parliament of the streets” in Davao, and that there were even claims he “arranged for meetings between foreign journalists and the [communist rebels, the New People’s Army].” Canuday, however, noted that older Davao journalists “initially failed to notice Duterte,” as he was “just in the sidelines” of the opposition.

Picture of Yellow Friday rally in Davao City, photographs by H.V. Paredes, from Mr. &

Ms., Nov. 4, 1983.

An interesting claim about Rodrigo during those times was made by presidential

sister Baby Duterte. In a documentary broadcast by GMA Network, she says Ferdinand Marcos himself called up Rodrigo to try to silence Soling, but the dutiful son refused. Historians Lisandro Claudio and Patricio Abinales took it as fact, stating in their chapter in the book A Duterte Reader that “the dictator believed he could call on Rodrigo to quell anti-government sentiment in Davao City, even if these protests were being led by the former’s own mother.”

It seems more likely that Rodrigo and Ferdinand Marcos never interacted after the

death of Rodrigo’s father. During the San Beda Law Grand Alumni Homecoming in November 26, 2016, while discussing Ferdinand Marcos’ recent burial in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, Duterte claimed that he had thrice tried to tender his resignation as a Davao City prosecutor because of his mother’s anti-government activities, but his requests were denied by his superior. He then segued into his family’s relationship with the Marcoses, stating that “there’s nothing close, we [himself or the Dutertes] did not have any dinner together [with the Marcoses] except one or two.”

SUPPORTED BY MARCOS’S POLITICAL ALLIES

Nevertheless, various sources note that he was supported by influential pro-Marcos

individuals when he ran for mayor of Davao City in the 1988 elections. David Timberman, in A Changeless Land: Continuity and Change in Philippine Politics, notes that Duterte won the mayoralty in 1988 because he was “backed by many of Davao’s traditional

politicians.” Clamor, citing a Mindanao Daily Mirror source, and a November 2005 article published in Davao Today name some of these politicians: former representative Manuel Garcia; Elias Lopez, KBL mayor of Davao City before the EDSA Revolution; and Alejandro

Almendras, Vicente’s cousin. Almendras’ friendship with Ferdinand Marcos blossomed while both of them were first-term senators between 1959 and 1965.

Almendras organized a political party called Lakas ng Dabaw for the 1988 elections. Clamor speculates that Rodrigo was chosen by the party as its candidate for mayor because “he had serious rifts” with Respicio, and also because of “personal ambition and consanguinial affinity with Almendras.” Davao Today states that Almendras “supported” Rodrigo’s candidacy, something that Soling initially did not; “one politician in the family is enough,” she said. Cory Aquino also did not support Rodrigo, endorsing Respicio

instead.

Rodrigo won in 1988, his first in an uninterrupted series of electoral victories. In addition to backing from pro-Marcos elites, Rodrigo, Clamor claims, won partly because of an “unholy alliance” between Rodrigo’s supporters and those of Jun Pala, another mayoral candidate and a key figure in the violent anti-communist rebel militia called Alsa Masa. To synthesize Clamor’s and Davao Today’s narratives, theirs was a divide-and-conquer tactic: Pala, secretly funded by Alemendras’ group, would take some of the votes that would have gone to Respicio, who supported Alsa Masa; Duterte, who was running with pro-Marcos

people but had a “leftist” reputation because of his mother, would take both pro-Marcos and anti-Marcos votes, as well as votes from areas under the control of the New People’s Army.

Clamor claims that the NPA’s support for Rodrigo came about due to its resentment

of Respicio’s alliance with Alsa Masa. Jonathan Miller, however, in his biography of Rodrigo, highlights the role in the would-be mayor’s 1988 campaign played by Leoncio “Jun” Evasco, an ex-NPA member detained for rebellion in North Cotabato and incarcerated and tortured in Davao City. Rodrigo was the public prosecutor who

succeeded in getting Evasco a five-year sentence, but, according to Miller, throughout his time in prison, Evasco was visited by Rodrigo. As with many other detained rebels, Evasco was freed after the EDSA Revolution. He became a key member of Samahan ng Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto, or SELDA, which later played an important

role in efforts to ensure that human rights violation victims of the Marcos regime are recognized and compensated. Rodrigo enticed Evasco to become his campaign manager in 1988; certainly, he continued to have some pull with the NPA at that time.

If Rodrigo (with Evasco) and Pala (with Almendras) did enact a vote division strategy, it worked like a charm: Rodrigo obtained 100,021 votes; Respicio, 93,676; Pala, 71,355; while two independent also-rans trailed behind. Clamor also reads the immediate concession of Pala—only a day after the then-manual elections—as further evidence that he ran for Rodrigo’s benefit.

THE ENEMY OF MY ENEMY MAY BE MY FRIEND

According to a declassified United States Department of State cable dated May 8, 1992, then Mayor Rodrigo Duterte was among Davao City’s “most vocal” backers of 1992 presidential candidate and Marcos crony Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco. That was even if Rodrigo was not a member of the Nationalist People’s Coalition, Cojuangco’s party.

Apparently, by 1992, Duterte did not see the need to stick close to the Davao-based Marcos loyalists who helped him win his first term as Davao City mayor in 1988. The 1992 cable highlighted how majority of Davaoeños “agree that Duterte’s Lakas ng Dabaw party is the best political machine in the city and will probably reelect the mayor.” But the presidential candidate that he backed lost. Cojuangco placed a respectable third in a seven-cornered fight, not only nationally, but also in Davao City.

In the 1998 elections, Duterte supported the presidential bid of Joseph Estrada,

long an ally of the Marcoses, who also had the backing of Cojuangco. The support was mutual; reportedly, Estrada even considered including Duterte in his senatorial line-up as early as in February 1997.

Ever the pragmatist, Duterte eventually allied himself with Gloria Arroyo, who succeeded Estrada after his “constructive resignation” in January 2001. In mid-2002, Duterte was appointed Arroyo’s anti-crime adviser. Apparently, the president wanted Duterte to have a bigger role in battling crime nationwide, but as reported by Philippine Star, Duterte said, “I don’t want to do anything other than [be an adviser] because I do not want to jeopardize my primary task as city mayor.” He was also quoted as saying that “I am only good in my

city or in the region but not in the entire country. I’m afraid I’d fail because I am not really cut out for it.”

Perhaps Duterte, already well-attuned to the volatility of Philippine politics, knew

that closely associating himself with any Philippine president might hinder the continuation of his dominance in Davao. Indeed, during the 2004 elections, Duterte’s association with Arroyo, who was gunning for a full elected term, was apparently severed and reconnected

numerous times.

During her elected term as president, Arroyo had become exceedingly unpopular, hounded by allegations of cheating in the 2004 elections, human rights violations, and corruption. Duterte once again did what a pragmatic politician would do. According to Grace Uddin of Davao Today, in April 2010, instead of endorsing Gilberto “Gibo” Teodoro Jr., Arroyo’s former secretary of defense and anointed successor, Duterte publicly declared his support for Senator Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III of the Liberal Party, who, through fortuitous circumstances, had become one of the most visible faces of the

anti-Arroyo political opposition. Uddin quoted Duterte as saying that “Aquino is easy to talk with. He is a principled man and clean.”

Carlos Isagani Zarate, then secretary general of the Union of Peoples’ Lawyers in Mindanao, told Uddin that Duterte chose the candidate likeliest to win, even if it meant supporting someone he had not been previously associated with over a friend like Estrada. Estrada at the time was attempting a Malacañang comeback. Indeed, the nationwide outpouring of grief for Noynoy’s mother, Cory Aquino, after her death on

August 1, 2009, made it clear that Noynoy was a viable contender for the presidency in 2010.

Even before Cory Aquino’s death, Duterte had already resolved to throw his lot with

the Liberal Party, which counted among its members Peter Tiu Laviña, one of his most trusted men. In a March 2015 article, Edwin Espejo stated that it was Duterte who took over as Davao City’s LP chair after Laviña bowed out in April 2009. In a November 18, 2009, press release from then Senator Mar Roxas’ office, Duterte was described as giving Roxas “the royal treatment” when the latter visited Davao City that month. The statement relayed that Duterte personally endorsed Roxas’ vice presidential bid because “limpio

ini”—“[Roxas] is clean.”

And so, for a brief moment in Philippine history, Duterte seemingly went full yellow, the color associated with the Aquinos and the non-violent protestors who fought against the Marcos dictatorship. Duterte even ran in 2010—for the position of vice mayor because of term limits—as a member of the Liberal Party. In an article posted on her blog in 2011, Raissa Robles pointed out that Duterte’s running mate, his daughter Sara, ran under PDP-Laban, whose vice presidential candidate, Jejomar Binay, was running with the Partido ng Masang Pilipino’s standard bearer, Estrada. Binay and Estrada were the top vote-getters in Davao City. In a way, the Dutertes were still shrewdly supporting a pro-Marcos presidential candidate while appearing to be very close to an anti-Marcos one.

THE 2016 DUTERTE-MARCOS CONVERGENCE

Besides having presidents of the Philippines as members, the Marcos and Duterte

families have many other things in common. For one, both families have patriarchs who had high positions in the undivided Province of Davao.

Wilson Leon Godshall, in the article “Can the Philippines Maintain Independence?,” published in Social Science in October 1935, says Mariano Marcos, Ferdinand’s father, was appointed Deputy-Governor-at-Large of Davao in 1931 by Governor-General Dwight F. Davis. Mariano’s duty, according to Godshall, “was to procure reliable and direct information concerning the state of affairs and to prepare a program to correct evils.” However, Godshall says when the acting governor was replaced, the new governor did not act upon Mariano Marcos’ intelligence or recommendations. Mariano eventually returned home to the Ilocos region, where he died during the Second World War. Thus, it was unlikely that he ever interacted with Vicente Duterte—appointed governor of Davao from 1958-1959 and elected to the same position from 1959-1965—as Vicente and his family were still in the Visayas before, during, and immediately after the war. Vicente was even appointed as acting mayor of Danao, Cebu—his birthplace—from January 1946 until July 1947, when Manuel Roxas appointed a fellow LP member in his place

Both the Marcoses and the Dutertes also have links with the wealthy Villar family and the Nacionalista Party, whose long-time president is former senator Manny Villar. To cite one instance of such ties, the 2019 senatorial campaign of Imee Marcos was partly financed by Manny Villar and his brother, Virgilio Villar, based on her Statement of Contributions and Expenditures. Duterte’s 2016 campaign was not personally financed by a Villar, but a stockholder in one of Villar’s companies, Marcelino C. Mendoza, was a top contributor.

Then President-elect Rody Duterte met with Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., who lost in the vice-presidential race, in Davao City June 11, 2016.Photo by Kiwi Bulaclac of Davao City Mayor’s Office. From Mindanews.

During the 2016 campaign, Duterte said that if he failed to curb criminality and corruption in the country within three months of becoming president, he would let Bongbong Marcos take over. He might have been playing to the crowd; Duterte made these remarks while campaigning at the Mariano Marcos State University in Batac, Ilocos Norte. Still, many

latched on to the Duterte-Marcos tandem, even if they were not running mates. Even the influential Iglesia ni Cristo went for the pair, officially endorsing them only a few days before the elections.

The results of the exit poll conducted by TV5 and Social Weather Stations, as reported by Mahar Mangahas in his Philippine Daily Inquirer column on May 14, 2016, suggest that the unofficial tandem was beneficial to both Marcos and Duterte. According to Mangahas, of Duterte’s 40 percentage points of the vote, “only 13 came from voters of his co-candidate Alan Peter Cayetano; the bulk of 18 came from Marcos voters, and another 6 from [voters of Leni Robredo, running mate of administration candidate Mar Roxas].” If the exit poll was representative of the actual vote, then of the 16.6 million or so votes obtained by Duterte, about 45 percent, or nearly 7.5 million, came from those who also voted for Marcos.

The results of the 2016 elections show that the Duterte-Marcos tandem was truly

formidable. Why, then, did they not formally run together? A member of Bongbong Marcos media team told VERA Files during the 2016 election campaign that Bongbong’s first choice as presidential candidate was Duterte. But he got impatient with Duterte’s dilly-dallying on whether to run or not so he teamed up with former senator Miriam Santiago, who was already very sick at that time.

There are other explanations. One may be because some who wanted to vote for Marcos did not like Duterte. Anti-communists, for instance, did not seem keen on supporting someone with known ties to the left. When Duterte controversially permitted a hero’s burial in Davao City for New People’s Army leader Leoncio “Ka Parago” Pitao in July 2015, for example, he received condemnation from anti-communist lawmaker Pastor Alcover of the Alliance for Nationalism and Democracy.

Perhaps some in the Duterte camp also considered themselves fundamentally opposed to

the Marcoses. As previously discussed, Duterte had ties to the Liberal Party, even becoming the party’s chairman in Davao City at one time. There was even talk that Duterte might become the LP’s standard bearer before Mar Roxas was formally proclaimed the party’s candidate in July 2015.

Moreover, though Duterte-Marcos seemed like a logical combination—strongman from the

south, son of a strongman from the north— there is no indication that Rodrigo Duterte and the Marcoses were an “item” before 2015.

It is hard to identify people within the inner circle of Duterte’s 2016 campaign—excluding financial contributor Antonio Floirendo Jr.—who have a long history with the Marcoses. Many in that circle are identified with post-EDSA Revolution administrations such as Angelito Banayo, Jesus Dureza, Emmanuel Piñol, Carlos Dominguez III, and Jose

Calida. Of that group, Calida is known to have supported a Duterte-Marcos tandem during the 2016 campaign, and, being the son of Ilocano settlers in Davao, also has ties to the ethnolinguistic group most closely associated with the Marcoses. But he had also been

linked to Ramos and served under the Arroyo administration at a time when the Marcoses considered themselves members of the opposition.

One who may have been a link between the Dutertes and the Marcoses during the 2016

election season is Salvador Panelo, currently Duterte’s Presidential Legal Counsel and spokesperson. Panelo actually ran for senator under Imelda Marcos’ Kilusang Bagong Lipunan ticket in the 1992 elections. He placed 125th among 164 candidates. A United Press International report, dated August 2, 1995, names Panelo as “a lawyer for the Marcoses” at the time Bongbong Marcos had been convicted of tax evasion by the Quezon City Regional Trial Court. Much later, Panelo would also include the Dutertes among his clients.

In March 2015, Panelo was quoted by Rosalinda Orosa of Pilipino Star Ngayon as saying that he knew a presidentiable willing to give way to Duterte in 2016. The would-be candidate was not named, but Panelo said that he/she wanted to be Duterte’s running mate. One wonders if this was Panelo brokering a Duterte-Marcos pairing.

A few months later, on June 15, 2015, the country finally saw Duterte and Bongbong

Marcos together, as the latter was a guest in the former’s weekly television program Gikan sa Masa Para sa Masa. While the focus of the interview was largely federalism, they also talked about the 2016 elections. At one point, Marcos said, “sumusunod lang ako kay

Duterte. He is my mentor in politics. Ako’y tagahanga lang.” Duterte jokingly replied, “hindi ko tuloy malaman kung ako ba ang presidente o siya.”

That interview was sufficient to fuel talk of a Duterte-Marcos tandem. Alas, it was not meant to be. Panelo, one of the few in Malacañang who has unmistakable ties to both the Marcoses and the Dutertes, may have failed as matchmaker.

Imelda Marcos greets President Duterte after his State-of-the-Nation address in July 2016. Malacañang photo.

The double issue of Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies, entitled “Marcos Pa Rin! Ang Mga Pamana at Sumpa ng Rehimeng Marcos,” notes that there may be two extremes among current Marcos loyalists: “(1) those who literally worship former president Ferdinand E. Marcos as a divine entity (absolute loyalty), and (2) those who at least appear loyal to him for electoral purposes (contingent loyalty).” The Dutertes seem to be closer to the latter. Duterte may have been the president who finally had Ferdinand Marcos buried in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, but that may not be a reliable indicator of who he is personally loyal to, given that he also allowed a hero’s burial for an NPA commander in 2015.

How long will the Dutertes see the Marcoses as politically useful? How long until the Marcoses fully reassert their continuing dominance in Philippine politics? Perhaps, while they are figuring out who will run as what in 2022, the rest of the electorate can find out if there are alternatives to political elites, whether from the north or the south, who have long worn out their welcome.