Originally published by Vera Files on May 27, 2024

Senator Imee Marcos, sister of the president, and daughter of the dictator, is known for making false claims or stating outright lies about herself, her family, and their legacy. Lately, she has been calling for a revival of her father’s Self-Reliance Defense Posture (SRDP) program, as if any attempts to have a self-reliant military or one buying from local manufacturers, were discarded after the Marcoses were deposed in 1986. This is not at all true.

Defense self-reliance not a Marcos brainchild

It is true that Imee’s father issued Presidential Decree no. 415 in 1974, “Authorizing the Secretary of National Defense to Enter into Defense Contracts to Implement Projects under the Self-Reliant Defense Programs and for Other Purposes,” which mandated a ₱100 million annual budget for the SRDP Program of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

But, as pointed out by a comprehensive (albeit now outdated) study on SRDP by Danilo Lazo and Juania Mercader, published in the Asian Studies journal, “The basic policy governing the self-reliance program can be found in Commonwealth Act No. 138” or the Flag Law, enacted back in 1936, “which requires preference for locally manufactured items in the procurement of supplies even if they cost up to fifteen percent higher than importing the said items.” Furthermore, Lazo and Mercader also note that “As early as 1948, the AFP has embarked into the long path of self-sufficiency especially when the Research and Development Center was organized to study the local manufacture of ammunition.” Self-reliance was not concocted by Marcos Sr. alone.

True as well, there are procurement-related restrictions that hamper support for the local defense industry, necessitating—at least for local contractors and the AFP—a new SRDP law. But this can be called for without resorting, as Imee does, to the old Marcos Golden Age myths. “Nasubukan na natin yan, at kinaya natin,” she said about SRDP during her father’s time in her 2024 Araw ng Kagitingan press release.

“Initiated by her father. . . . Under the program, the Philippines was producing M-16 rifles, hand grenades and various other ammunition, patrol boats, and military jeeps, among others,” her PR bit affirms.

Pushing for her father’s SRDP in Agusan del Sur on May 4 made the Philippine Daily Inquirer dig up a press release her office issued in February 2023, where she says, “In the 70’s to early 80’s, our SRDP was already producing M-16 rifles under license, steel helmets, hand grenades and other ammunition, handheld radios, Jiffy jeeps. It also created jobs and minimized foreign spending.” In the press release, Imee also “explained that Filipino manufacturers used local materials besides the imported parts from which technological know-how was gained, with the National Science Development Board [predecessor of the Department of Science and Technology] supporting research and development.”

More recently, during a May 18, 2024 interview with Zamboanga City radio station Magic 95.5, she said, “noong panahon ng tatay ko, may self-defense, may self-reliant defense posture…But now we virtually have no defense manufacturing at all. Ultimo bala natin imported. ‘Yung mga guns that we used to make are now imported from South Korea…Now it is all imported and we are struggling to rebuild.”

In all these statements, Imee asserts that her father’s SRDP program went without a hitch—we were producing what we needed on our own. The story of the oft-highlighted M16 manufacturing project, however, illustrates some of the Marcos-era issues glossed over by Imee and other SRDP law advocates: perennial funding issues, continued foreign reliance even for raw materials and supplies, cronyism, mismanagement, and misguided attempts at state-led arms exportation.

The Arms and Munitions “Metal-workers” of the ’70s

The Government Arsenal (GA), an agency under the Department of National Defense (DND), was created in 1957, through Republic Act No. 1884. This Garcia-era law states that “The Government hereby declares its policy to achieve within a reasonable time self-sufficiency in small arms, mortars, and other weapons, ammunition for these weapons, and other munitions for the use of the military establishments.” Other provisions of the law talk about the establishment of a small arms munitions plant “and all other plants,” as well as an initial appropriation of over ₱ 5.6 million. The next significant event in the GA story is the groundbreaking of the GA’s site in Limay, Bataan. It does not mention attempts in between to secure what eventually became a key source of funding for the Arsenal: Japanese war reparations.

Hilarion Henares Jr. claims that he drew up the plan to fund the Arsenal using reparations back when he headed the National Economic Council under the Macapagal administration. In October 1964, Macapagal publicly announced that reparations were going to be utilized to build a US$3 million munitions plant. Henares (in his book Beast and Beauty) and Macapagal (in his book A Stone for the Edifice) stated that the Japanese government was resistant to funding the plant proposal because doing so may be seen to contradict Japan’s constitutional renunciation of war, but they explained that the plant’s products would only be used for internal peace and security, not defense against external threats. Macapagal personally appealed for the proposal’s approval to Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda, who agreed to use reparations to construct a “metal-working plant” for the DND.

Several reparations contracts for “metal working and allied equipment” were executed between Japanese contractors and the Department of National Defense between November 1965—in the last days of the Macapagal administration, shortly after it became clear that Marcos Sr. beat Macapagal in the elections that year—and December 1975. The total value of these contracts exceeds US$ 8.6 million (1 USD = 3.9 ₱ from 1965-1969, 1 US$ = 6-7.2 ₱ from 1970-1975). A memorandum from secretary of defense Juan Ponce Enrile to Marcos Sr. dated January 6, 1971, confirms that the GA was heavily reliant on Japanese reparations, not only for equipment (the first of which was delivered in 1968) but also for personnel training.

Enrile, in an article in the 1978 Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook, stated that “the actual integrated manufacturing process [of the Arsenal] started only in the early part of 1974.” Enrile also stated that by 1978, the Arsenal’s plant was also producing 7.62 mm ammunition, “a pet project of the president,” and M16 (M161A) automatic rifles, “with most of its parts locally manufactured in joint venture with local private firms.” The 1981 propaganda book The Marcos Years: Achievements Under the New Society described the Philippines’s in-country M16 production capability as a highlight of the SRDP Program: “M-16 rifle is now assembled within the Government Arsenal site in Bataan, with all the rifle parts manufactured by local firms.”

Armscor and Elitool

Two firms prominently associated with arms manufacturing for the AFP are the Arms Corporation of the Philippines (Armscor) and the Elisco Tool Manufacturing Corporation (Elitool). Headquartered in Marikina, Armscor traces its roots to Squires Bingham Manufacturing, Inc., which was established as a firearms manufacturing company in the 1950s. A reorganization led to the creation of Armscor in 1980, with Squires Bingham becoming the former’s parent company. According to a 1986 position paper from Armscor, it sold a total of ₱ 23.8 million in arms and munitions to the AFP between 1981 and 1983 and did not make any sales to the Armed Forces beyond mid-1983. The position paper was submitted to the Presidential Commission on Good Government, in relation to publicized claims that Armscor was part of a ring of suppliers connected to former AFP chief Fabian Ver. Armscor weathered the accusation, continuing to thrive until today, with subsidiaries and customers worldwide; it has never been dependent on local defense contracts for profit.

Elitool was a different story. They were the principal company involved in the production of M16s mentioned by Enrile. But in the early 1970s, unlike Armscor/Squires Bingham, it was not primarily known as an arms manufacturer. It was known for making metal hand tools. The “Eli” in the name comes from the Elizalde Group of Companies. Manuel Elizalde Jr., a Marcos associate, owned the controlling shares of Elitool.

From the start of the M16 manufacturing project, months before Marcos Sr.’s SRDP decree was issued, the main entities involved were the Government Arsenal and Elitool. The Government of the Philippines (GOP) and Colt Industries approved ten-year licensing and transfer of technology agreements for the production of M16s on September 17, 1973, similar to a deal struck with the government of South Korea. According to a declassified US State Department cable dated September 18, 1973, the GOP and Colt agreed to a phased in-country production schedule, wherein the former would initially make direct purchases of several thousand M16s (months 0-9), then assemble the rifles in country, with locally sourced content increasing until year 6 (within 1979-1980) when the rifles will be produced in the Philippines with 100 percent local content. The cable states that the bolt and barrel manufacturing and final assembly were the GA’s responsibility; Elitool would manufacture everything else, “except those subcontracted out,” in its facilities within Metro Manila.

Just as the Arsenal relied on foreign funding to start making munitions, the rifle project needed foreign funding to get off the ground. The September 18, 1973 cable states that the Secretary of National Defense (headed by Juan Ponce Enrile) requested the US government for “an FMS [Foreign Military Sales] loan to partially finance the rifle plant project. Under the GOP request, the FMS loan would be for $15,614,000, divided into two annual installments [between 1974-75].” The cable also states that the GOP was going to assist Elitool “obtain a peso loan equivalent to approximately US$ 6,380,000” to further finance the project. Based on the transcripts of the US House of Representatives hearings for foreign assistance and related agencies appropriations for 1975, the memorandum of understanding for the FMS credit was signed in May 1974, and the repayment of the credit must be “in the form of principal and interest charges.”

Another agreement, specifically between the GOP (represented by Vicente Paterno, then chair of the Board of Investments) and Elitool, executed in October 1973, stated that the former would supply imported raw materials and production supplies to the latter. The original GOP-Elitool agreement also stated that the government would construct facilities in Fort Bonifacio (for bolt and barrel production) and in the GA complex in Bataan (for final assembly) at no cost to Elitool, who will supervise the construction of these facilities. The government would shoulder over ₱ 160 million in costs; Elitool would shoulder at least ₱ 42 million. Both, again, would rely on loans.

The expensive project involving the two “metal workers” yielded results. By April 1981, the GA and Elitool had delivered nearly 158,000 M16s out of an order of 172,500 units (150,000 rifles and 22,500 equivalent spares) though the project continued to rely on some imported materials/supplies obtained through Colt, as a “purchasing agent,” by the AFP. In April of that year, shortly before the agreement between the GOP and Elitool was set to expire, an amendment to the total order was made; Elitool was tasked to manufacture another 60,000 rifles, using SRDP funds, costing a total of ₱ 130 million.

Arms-dealing ambitions

What principally brought about the increase was a plan to export M16s to neighboring countries such as Indonesia and Thailand. General Romeo Espino, AFP chief, in his January 1981 proposal to Enrile to extend Elitool’s contract and amend its deliverables, stated that they could at the time undercut Colt itself by US$85 per rifle and make deliveries immediately, tapping into existing stock (ex-stock) manufactured by Elitool.

A total of ₱ 130,000,000 in SRDP funds was to be tapped for the extension-exportation scheme. With the approval by Marcos Sr., a deal was struck between the AFP and Elitool in November 1981: the former lent (or effectively “returned”) an initial 20,000 rifles to the latter for exportation, with the condition that Elitool will replenish the “borrowed” rifles with proceeds from overseas sales. It seemed like a win-win, as the rifle project was proving to be financially burdensome by that time, and the deal would ideally result in more rifles for the AFP and the sustainability of GA-Elitool’s firearm-manufacturing capability.

If the value of SRPD exports was any indication, the Philippines was hardly on its way to becoming a well-patronized defense materiel manufacturer in the early 1980s. In an article in the 1983-1984 edition of the Fookien Times Yearbook, AFP chief of staff Gen. Fabian Ver said that by November 1983, SRDP exports—including tactical radios, practice bombs, and small arms and ammunition—had earned a total of less than USD 8 million since 1974 (1 US$ = 11.11 ₱ in 1983).

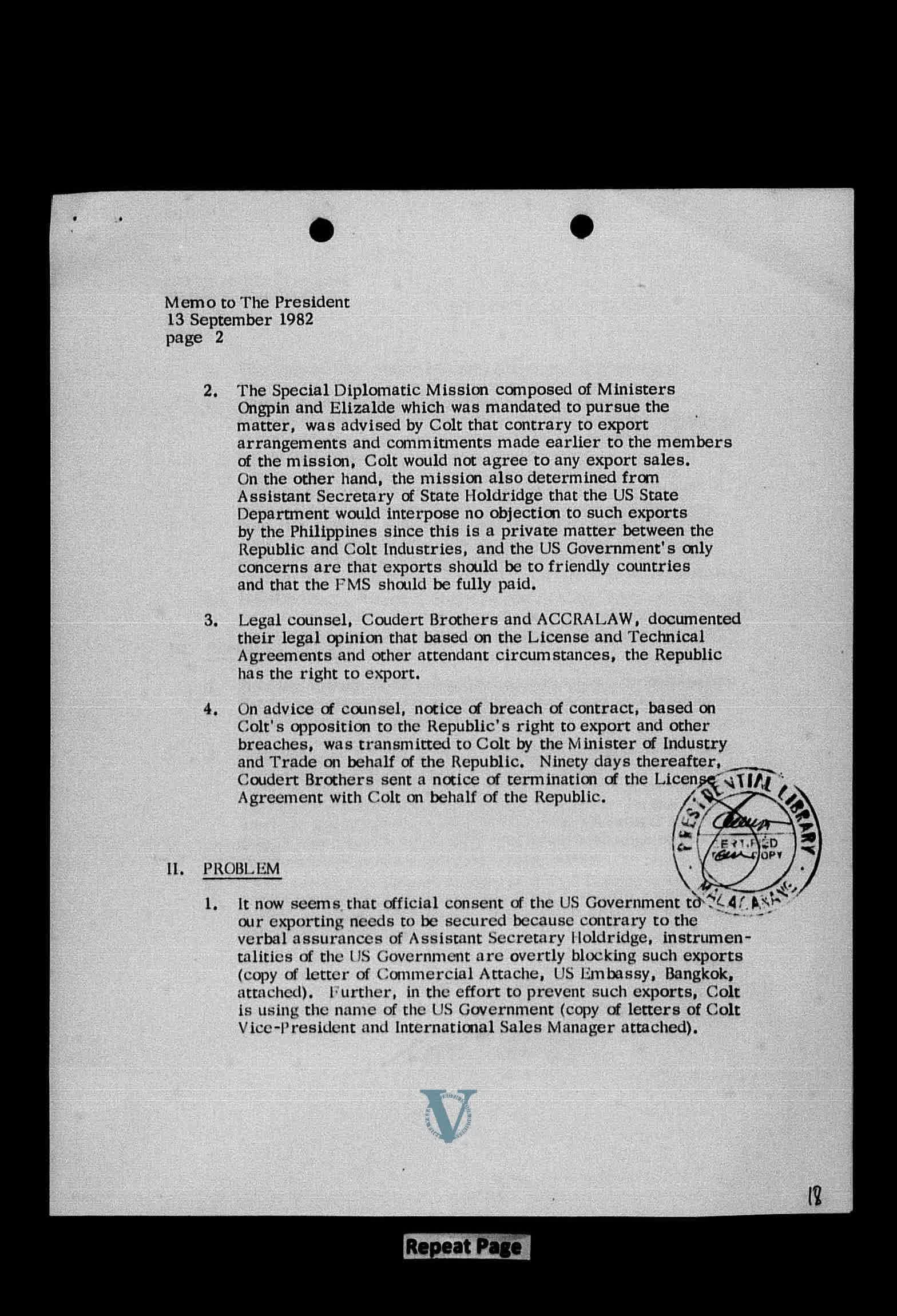

Exportation, however, was not readily permitted by the existing agreements with Colt and the United States government. Department of State cables show that the US was supportive of the project as a means of helping the Philippines develop self-reliance, resulting in foreign exchange savings to the Philippines and potentially strengthening local support for the retention of US bases. But cables also show that the US government did not want the Marcos government to sell rifles received under the production program without the former’s consent, while the final agreements with Colt specified that the products of their licensee could not be sold to other countries. According to James Everett Katz, in the 1984 book Arms Production in Developing Countries, “Although Colt had agreed in the September 1973 agreement to the production of an additional 65,000 M-16s for export, the U.S. government insisted in the May 1974 agreement that the provision be dropped.”

Katz further details failed attempts to work out an exportation deal: “[In early 1981,] Colt was willing to allow the Philippines to export 65,000 M-16s, but it also imposed a number of new conditions. Colt wanted to determine to which countries the Philippines could export, to require that raw materials be ordered through Colt, and to charge a royalty fee based on the Colt price for an M-16.” The Philippines did not find these conditions acceptable. Colt and the US government made moves to prevent overseas sales deals. For instance, Colt sent a letter in October 1981 to the Minister of Defense and Security of Indonesia, stating that “the contracts between Colt Firearms and their various licensees do not allow them to sell either rifles or parts to other countries.” A similarly worded letter was sent to the chief of the Ordnance Department of the Royal Thai Navy in June 1982, not by Colt, but by the Counselor for Commercial Affairs of the US Embassy.

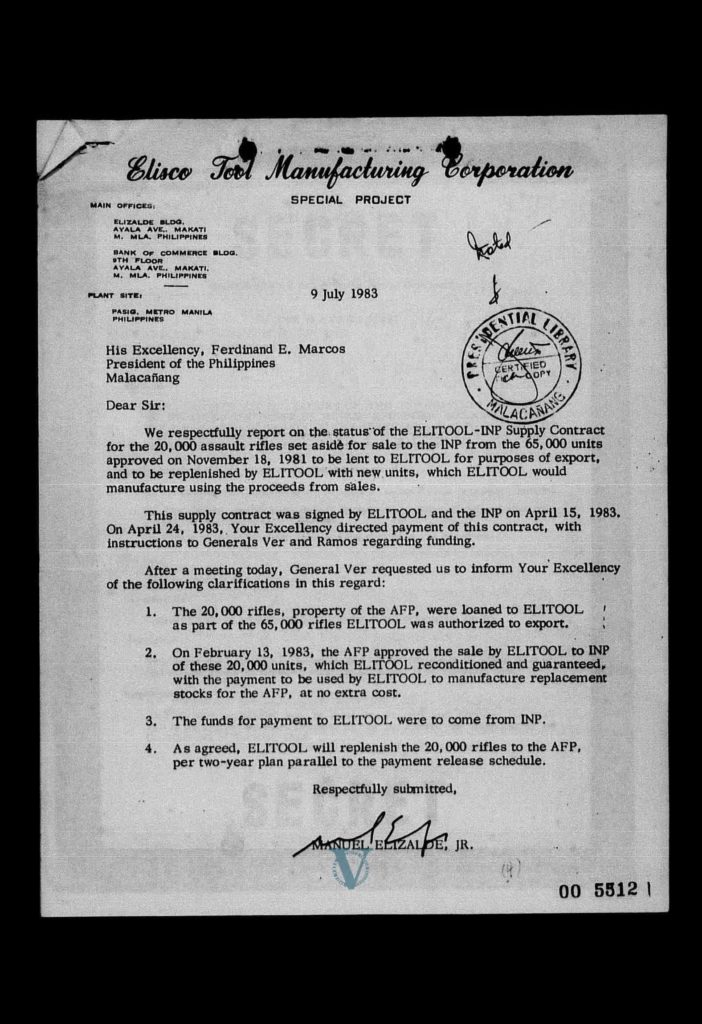

Thus, by mid-1982, Elitool had 20,000 rifles with nowhere to go. Instead of returning the rifles to AFP, however, another deal involving the guns was approved by Marcos Sr., this time between Elitool and the Integrated National Police (INP). Pursuant to agreements made in April and September 1983, the INP, headed by Philippine Constabulary chief General Fidel Ramos, bought the rifles from Elitool, and Elitool was to use the proceeds of the sale to fund the replacement of the 20,000 guns for the AFP.

Gen. Fabian Ver opposed Elitool-INP contract

General Ver did not like the deal. Writing to Marcos in July 1983, Ver insisted that the 20,000 rifles were AFP property, so “any agreement concerning the sale of the 20,000 rifles should be between the AFP and INP.” He wanted the ₱ 57 million that the INP was going to pay Elitool to go to the AFP instead. Marcos Sr. did not approve the proposal.

Elitool by then had yet to complete the original 172,500 M16 order, much more the 60,000 addition, largely because of the cancellation of the GOP-Colt agreements in June 1982 precisely because of the failed exportation plan. Without Colt, the AFP needed to find another raw materials and supplies purchaser, which it eventually did in 1983.

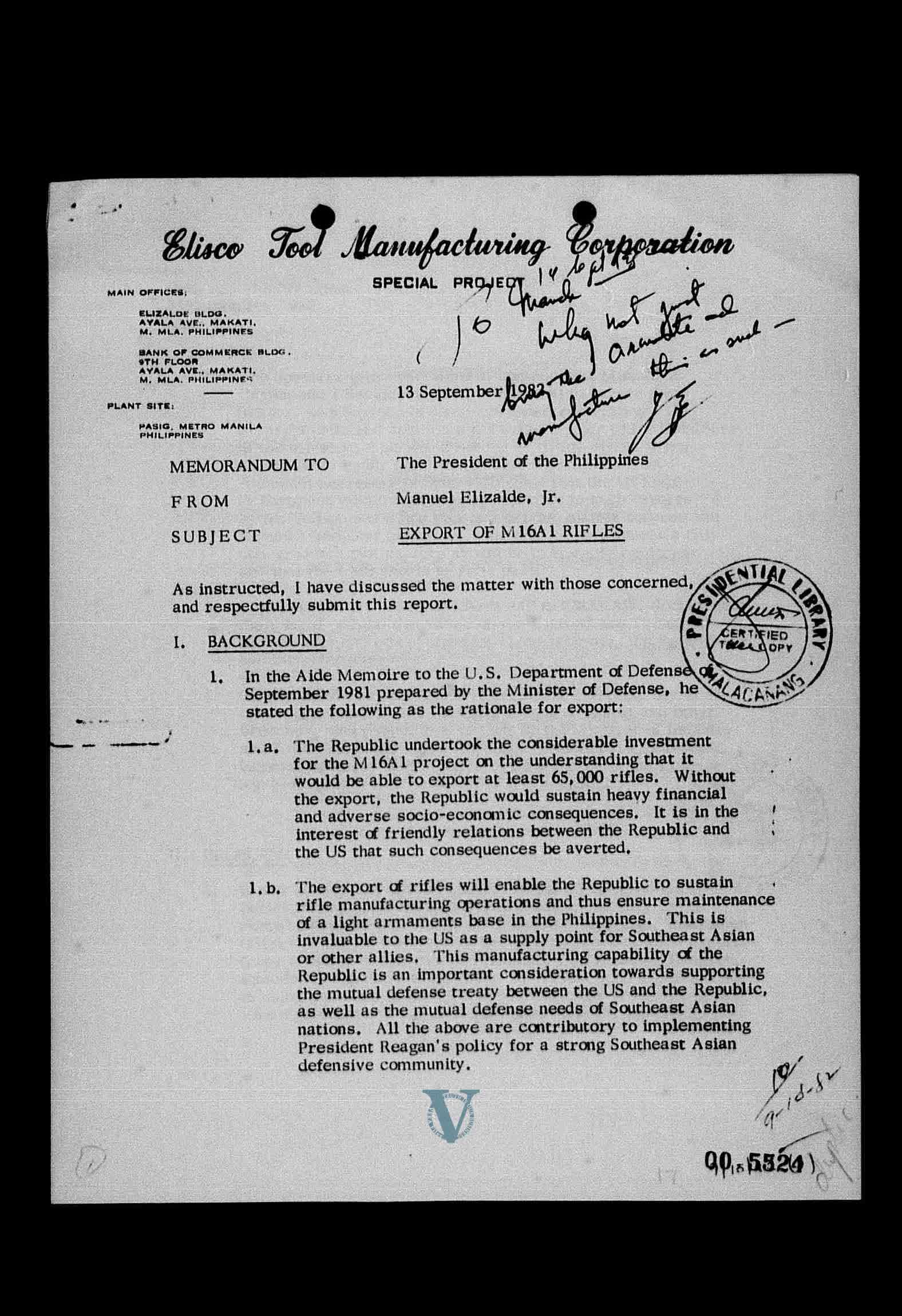

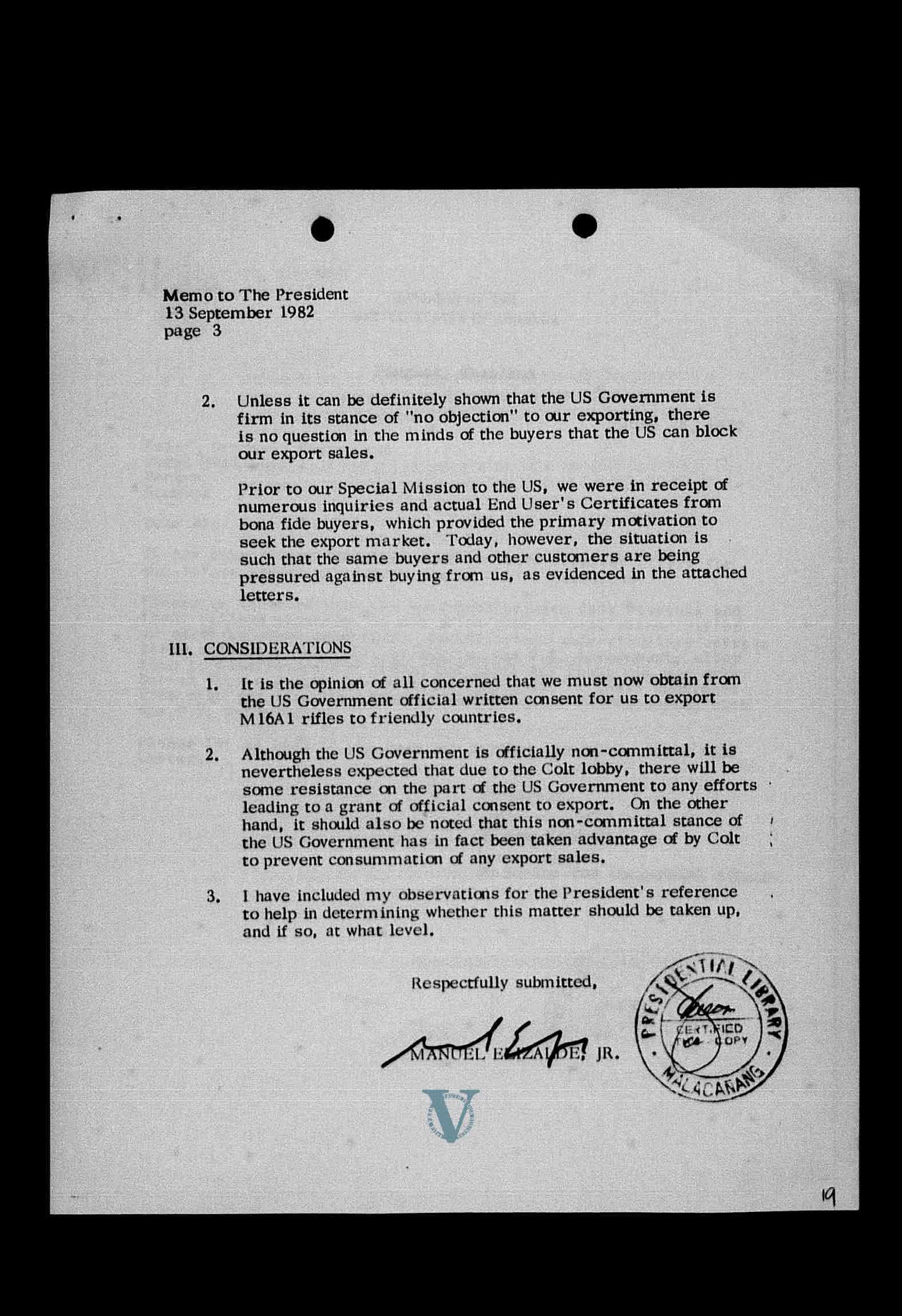

According to Elizalde, in a letter to Marcos Sr. dated September 13, 1982, it was the Philippine government that initiated the termination of the GOP-Colt agreements because of the export issue. He also emphasized that there was a need to pump money to the rifle program; “without the export, the Republic would sustain heavy financial and adverse socio-economic consequences,” Elizalde said.

Letter from Manuel Elizalde, Jr. to Ferdinand E. Marcos, on the export of M16A1 Rifles, with handwritten reply of Marcos, from the PCGG files

Elizalde’s letter was a cry for help to Marcos Sr., imploring that the GOP “obtain from the US Government official written consent for us to export M16A1 rifles to friendly countries”; the president’s handwritten reply was, “Why not bring the Armalite and manufacture this as such.” Thus, in 1983, Marcos’s recommendation led to Elitool obtaining the exclusive rights to manufacture, use, and sell Armalite’s AR18, AR5, and AR100-series rifles instead of Colt M16s. Armalite was already struggling financially during the early 1980s, and the M16 was patterned after Armalite’s AR15, so effectively selling to Elitool made sense. However, Armalite was never fully compensated during the time of Marcos Sr.; a May 15, 1986 communication to Jovito Salonga, head of the PCGG, from then AFP chief Fidel Ramos, states that by that time, Armalite had complied with about 90 percent of its commitments despite incomplete payments “due to budgetary constraints.”

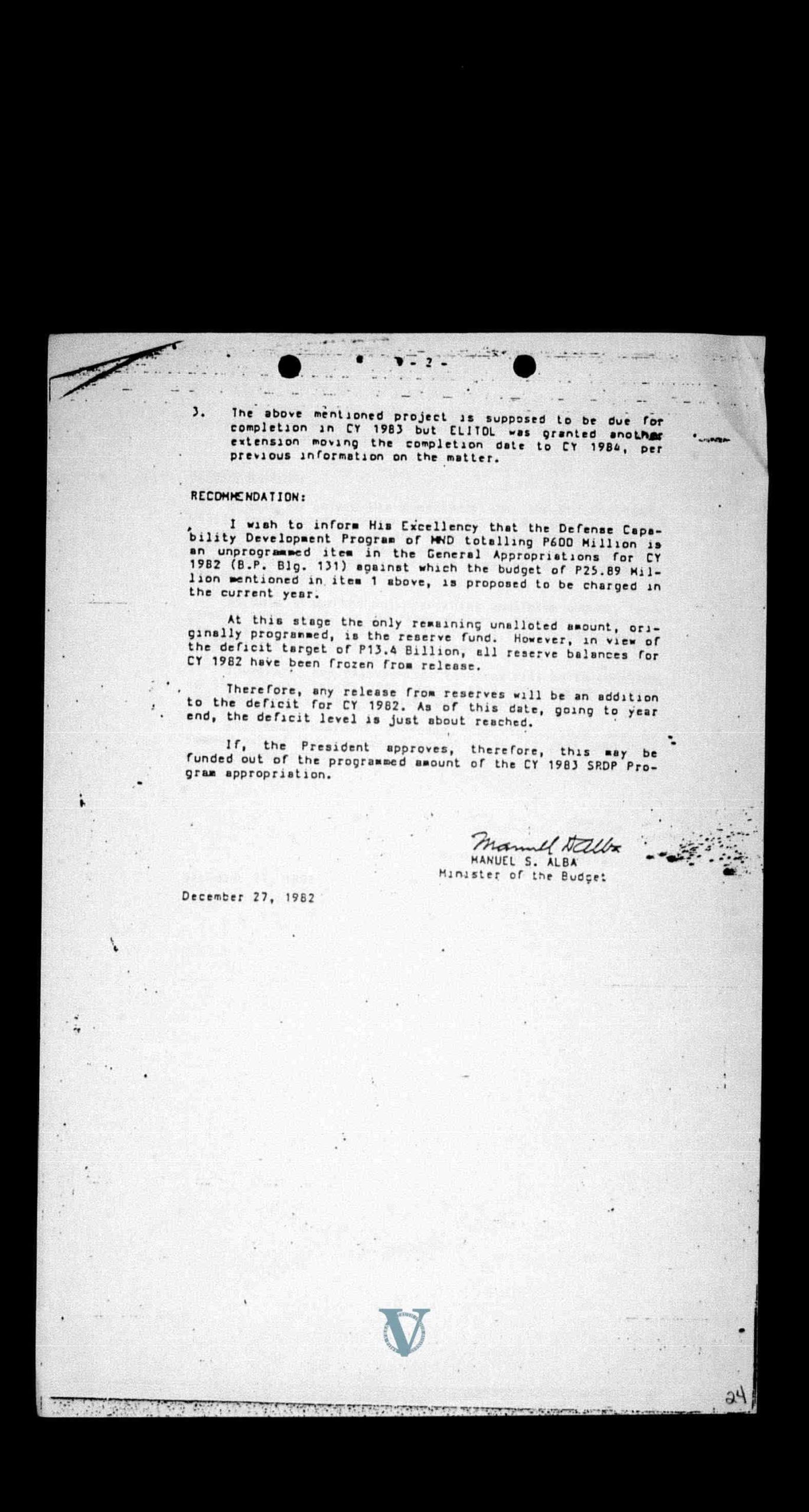

There were budgetary constraints regarding the extended rifle production project even before the deal with Armalite. In December 1982, Budget Minister Manuel Alba sent a memorandum to Marcos on the “Additional Costs of the AFP SRDP Project, the M16 A1 Rifles.” By then, Alba said that ₱ 45 million had already been released (even without any additional rifles being produced). Defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile was asking for the release of an additional ₱ 25.89 million from the Defense Capability Defense Program (DCDP) of the Ministry of National Defense to increase the down payment to Elitool. Alba noted that only the reserve fund of the DCDP could be tapped, but doing so would increase the country’s already guaranteed end-of-year budget deficit. Alba suggested that they tap the 1983 SRDP appropriation instead, to which Marcos Sr. agreed.

Memorandum from budget minister Manuel Alba, on additional costs of AFP SRDP project, the M16 A1 Rifles, with handwritten approval of Ferdinand E. Marcos, from the PCGG files

In any case, even with funds from the INP, a new purchasing agent for the AFP, and the Armalite license, Elitool was still unable to replace the 20,000 rifles it borrowed when they became due in 1985. A year before, however, General Ver was still claiming that the Philippines was doing so well in rifle production that it was ready to export M16s. During a February 1984 visit of his Indonesian counterpart, Gen. Leonardus Benjamin Murdani, Ver presented the former with a locally manufactured M16 as a gift, and was quoted by the local media as saying that “the Philippines is ready to export locally manufactured armalites (M-16s).” A declassified US State Department cable noted that as per defense ministry source, “Although [the GOP] is capable of exporting M-16 [it] was not now ready to do so,” because “problems with Colt would have to be sorted out first.”

The arms deal under the Cory Aquino administration

After the fall of the Marcos regime, Elitool offered to return the proceeds of the rifle sale to the INP, as it felt that it was exceedingly difficult to fulfill its obligations due to circumstances beyond its control. In an August 1987 letter to Col. Danilo Lazo, Acting Deputy Chief of Staff for Materiel Development of the AFP, Deogracias Salumbides, executive vice president and general manager of Elitool, said that they were unable to “effect immediate replacement of the rifles” because of “the unforeseen delay in the rehabilitation of government- owned facilities of the M16A1 Project” and the “failure of the AFP to provide the necessary spare parts and supplies.” “Manufacturing cost has gone up over the years,” continued Salumbides, “and even if we assume that production would presently commence, sales proceeds [presumably from sales to the AFP] will not be sufficient to cover the total replacement cost of the project.”

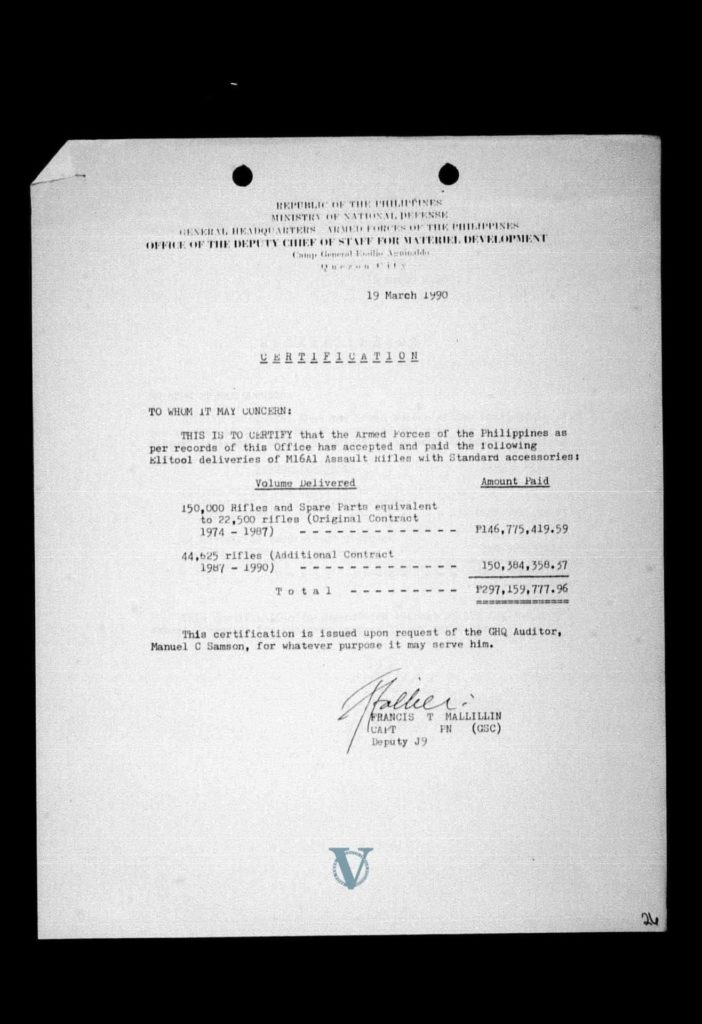

Nevertheless, in 1989, the Corazon Aquino administration, required Elitool—chaired by Manuel Elizalde’s sister-in-law, Josine Loinaz Elizalde—to deliver what it owed. Elitool eventually completed the original 172,500 order in 1987, and by March 1990 had delivered an additional 44,625 M16s. The plans to locally manufacture AR18s did not prosper, but the GOP, as represented by then Secretary of National Defense Fidel Ramos, did contract Elitool to also produce 3,500 prototype AR100 rifles, as well as another 12,000 M16s to be delivered between 1990-1991. It is unclear if Elitool was able to deliver the additional orders, or when Elitool formally folded up. In 1995, the rights to the Armalite trademark were sold to an American company, Eagle Arms.

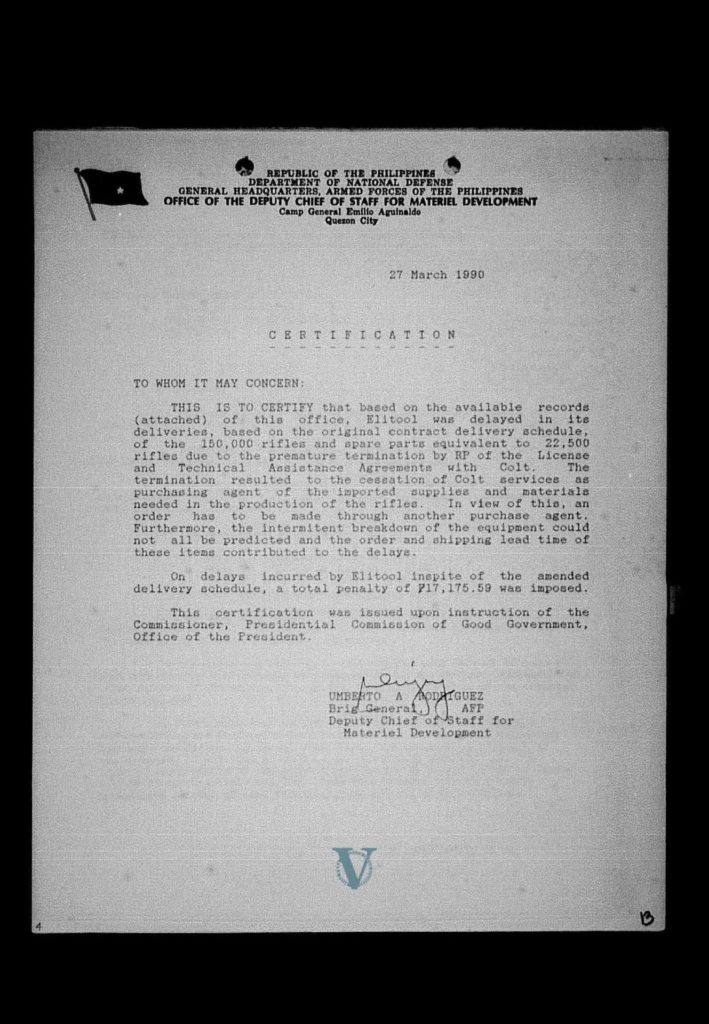

A certification from BGen. Umberto Rodriguez, Deputy Chief of Staff for Materiel Development, dated 27 March 1990, noted that Elitool was fined a total of ₱ 17,175.59 for the delay in completing the original 172,500-rifle order. While Ramos was running for president in 1992, the INP sale issue was brought up against him, but no one was ever found to be criminally liable for the deal. When Ramos became president, he attempted to nominate Manuel Elizalde as ambassador to Mexico, but withdrew the nomination, reportedly because the public brought up the Marcos ties of the Elizaldes.

According to a report by Luz Rimban, remnants of Elitool eventually formed Precision Technology Producers’ Cooperative, later Precision Munitions Inc., that, in the 2000s obtained contracts to refurbish the same Elitool M16s for the Philippine National Police, though questions were raised about the quality of their work. The Arsenal is far from what it was when it was funded by war reparations and FMS credits; it continues to produce munitions and small arms (of small quantity), and can repair, refurbish, or upgrade/convert rifles, but not mass produce them. Corazon Aquino’s Executive Order No. 292, or the Administrative Code of 1987, contains provisions on the GA, including one that mandates the Arsenal to “Formulate plans and programs to achieve self-sufficiency in arms, mortars and other weapons and munitions.” It was reported in 2016 that the Commission on Audit found that the GA was still using ammunition-producing machines between 12-39 years old, meaning it was still using equipment from the 1970s. News on COA’s most recent assessment stated that the GA missed its ammunition production targets, with the representatives from the GA attributing their output issue to old, failing machinery.

Today’s SRDP

Today’s SRDP proponents and advocates need to look at the supposed Marcos-era “success stories,” like the M16 project, with more sober eyes. Will they advocate contracting existing arms manufacturers, or help build up would-be crony firms via capital-intensive, debt-financed, and ultimately unsustainable projects? Will they push for exports to the possible detriment of building up domestic defense capabilities? Will making the Philippines, by hook or by crook, a global arms dealer be made part and parcel of self-reliance?

The House’s SRDP bill, HB 9713, and the Senate’s version, SB 2455 (of which Imee is a co-author), have both been approved on third reading, and, as of May 22, 2024, are set for bicameral conference committee reconciliation. Both contain a provision mandating the government to “promote the export of locally made materiel” and local enterprises to other countries; the Senate version encourages, while the House version requires, the allocation of funds “for the purpose of such promotion.” The Senate version orders an initial ₱ 1 billion to be appropriated for the implementation of the SRDP program.