Originally published by Vera Files on January 23, 2021.

Senator Imee Marcos just has to butt in. She defended President Rodrigo Duterte’s low regard for women in politics only to remind us of her father’s similar, if not more atrocious view.

Just before 2020 ended, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte emerged as the presidential frontrunner in a Pulse Asia survey conducted for the period November 23–December 2. The results also show that she is statistically tied with Senate President Vicente Sotto III and Manila Mayor Isko Moreno in the vice-presidential race.

Speaking at the inauguration of the Skyway Stage 3 project on January 14, 2021, Duterte advised his daughter against seeking the presidency. Right after saying that he would not fantasize about a term extension, he said, “And my daughter, niudyok man nila. I have told Inday not to run kasi naaawa ako na dadaanan niya na dinaanan ko. Hindi ito pambabae. Alam mo, the emotional setup of a woman and a man is totally different. Maging gago ka dito.” (My daughter, they are prodding her. I have told Inday not to run because I would pity her if she goes through what I experienced. This is not for women. You know, the emotional setup of a woman and a man is totally different. You’ll be made into a fool here.)

After two days, Imee Marcos, asked by DWIZ radio to respond to Duterte’s statement, mentioned Sara’s miscarriage in 2016, and said, “Kawawa nga ‘yan e, kasi hirap na hirap siya. Sabi nga niya napaka burned out na, ayaw na niya mag mayor e kasi hirap na daw siya.” (She’s pitiful because she’s having a difficult time. She said that she is burned out and that she does not want to be mayor anymore.)

Unprompted, she continued, “Pero ‘yung mga reaction na very misogynistic and chauvinist na ‘not a job for a woman,’ naintindihan ko ‘yun e kasi yung tatay ko ganun din e, sinasabi sa akin na si Bongbong ang dapat pumasok sa pulitika, period. Pero yung nanay ko, ako, parati siyang very protective kasi bakbakan ‘yan e, sabi niya. ‘Wag na nga ‘yung mga babae, kawawa naman.”

(But the reaction that [the statement] was very misogynist and chauvinist, that [the presidency] is ‘not a job for a woman,’ I get that because my father used to say the same thing. He used to tell me that it should be Bongbong who should enter politics, period. He was very protective of me and my mother because he says that [politics] is a down and dirty fight. Women should shy away from it. They should be pitied.)

“I think it’s not out of being chauvinistic, that you have inferior capabilities as a female, but more as a father who worries about pushing his daughter out to the brutish world of politics,” added Imee, who just has to conjure the ghost of her father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, whenever the opportunity presents itself. In her statement, Imee defended the idea that women should not be in politics, and that they should seek the protection of powerful men. According to her, this is not misogyny or chauvinism, but an act of love and concern.

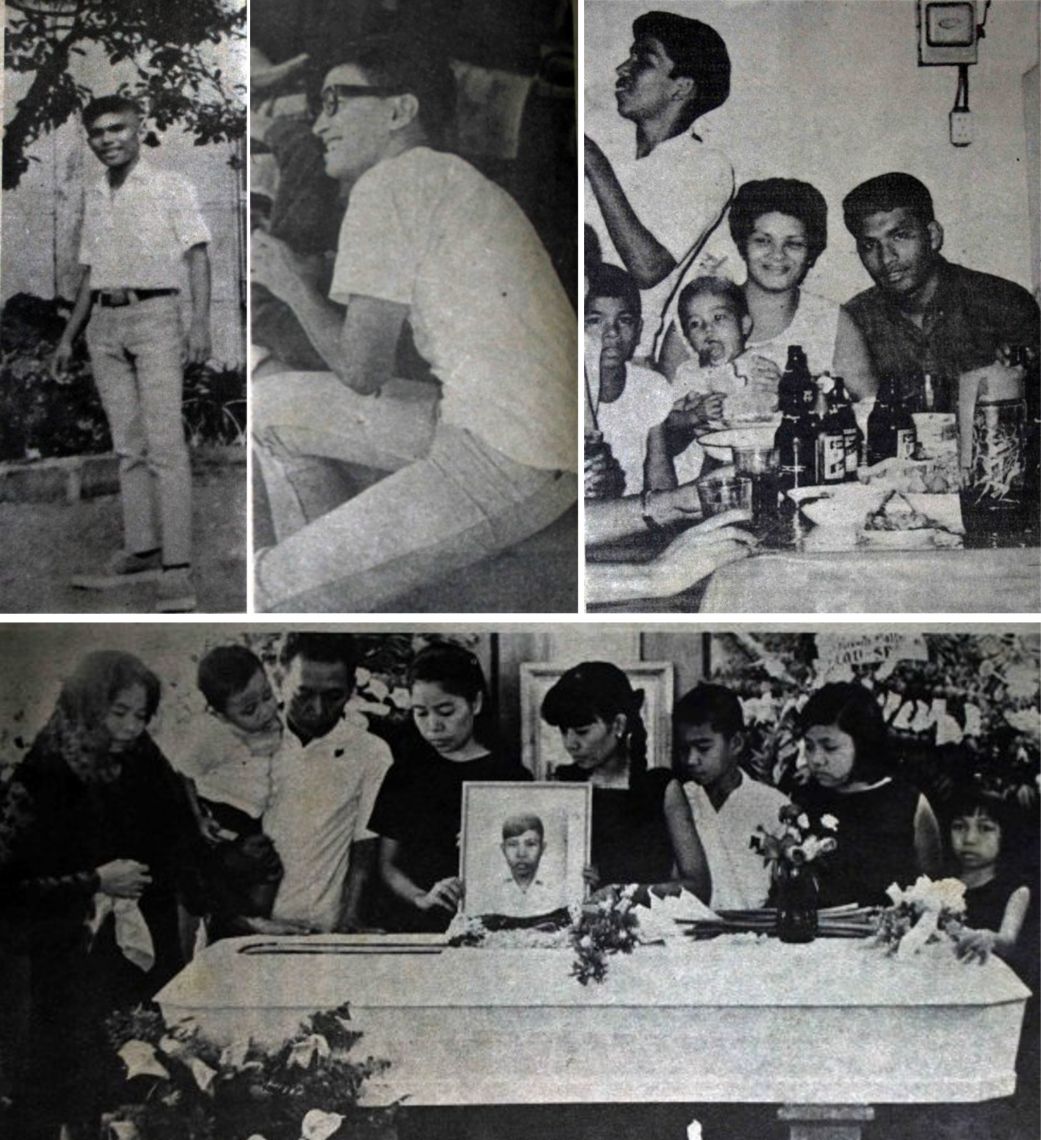

First, Imee’s claim that her father shielded her from “the brutish world of politics” is untrue. At 21 years old, Marcos appointed her national chair of the Kabataang Barangay (KB), an organization for the youth to engage in politics. In other words, the late dictator gifted Imee with her own political network. In 1977, in order for Imee to qualify as a KB member and leader, Marcos signed Presidential Decree (PD) 1102, adjusting the age limit for members from 15–18 to 15–21 years old. Imee stayed as national chair until her family was forcibly removed from power by the 1986 Edsa Revolt. The decree was signed a day after Archimedes Trajano was tortured and killed for asking in a public forum why the president’s daughter had to lead the KB.

Meanwhile, a declassified diplomatic cable from the American Embassy in Manila to the Secretary of State in Washington DC dated August 9, 1978 revealed that Marcos was leveraging his daughter in pacifying “radical” KB members on the verge of conducting anti-US bases strikes and demonstrations in Clark, Subic, and other neighboring towns. One can reasonably say that Marcos did not protect his daughter from the “brutish world of politics.” She was long in on the family business.

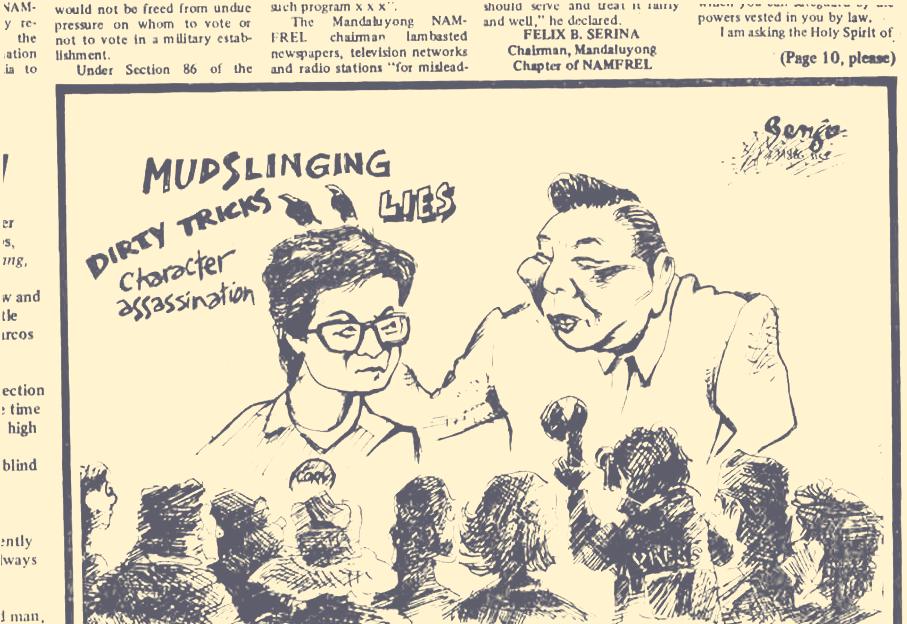

And lest Senator Marcos forgets, or claims that she is too young to have remembered, her father unleashed a barrage of sexist remarks—from patronizing to utterly demeaning—against Cory Aquino during the 1986 snap presidential election.

Under pressure from the United States to undertake sweeping political reforms, and amid growing frustration with his administration domestically, Marcos called for a snap election on November 3, 1985 in an attempt to prove his mandate. On December 5, 1985, Cory Aquino, wife of the slain opposition leader, Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr., announced her candidacy. This came three days after Sandiganbayan acquitted Armed Forces of the Philippines chief of staff General Fabian Ver and 25 others in the murder of her husband at the tarmac of the Manila International Airport, a decision that enraged many.

In her first press interview after announcing her candidacy, Aquino declared she wanted a debate with Marcos on live TV. Initially, Marcos said he was willing to do so. A Tokyo-based media service quoted him as saying, “My conversations with ladies have always been pleasant and I don’t think that this will be different from others. I presume I will survive this encounter.” Two weeks later, Marcos publicly refused to debate with a woman but would only have a “friendly conversation” with her. Aquino responded with, “Why not, I am all for a friendly conversation.”

In January 1986, Aquino renewed her challenge, but Marcos refused once again. As carried in the US State Department Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) daily report on January 27, 1986, the government-run Maharlika Broadcasting System (MBS) had this to say:

Had the debate pushed through, Cory’s lack of government programs, her flip-flopping position on vital issues, and her abysmal ignorance of statecraft would have been exposed to full public view, embarrassing the lady no end. Mr. Marcos, a formidable debater, was too much of a gentleman to let such a thing come to pass.

It is on record that Mrs. Aquino, much like a woman changing clothes, has altered her own position on such issues as the U.S. bases, participation of Communists in her government, and recognition of independence of the Muslim regions in the south. With her shifting stance on these important issues, how can there be any meaningful debate?

The much-awaited debate took almost two months to happen. Veteran newscaster and host of the ABC News program Nightline Ted Koppel casted doubt that Marcos will ever accept the challenge, saying Marcos’s advisers “want him to duck the debate.”

ABC News had agreements with both candidates two and a half weeks before the scheduled debate on February 6. But just two days before this, Marcos said the confrontation should not take place on American TV, but on Philippine television, which could have happened had he accepted Aquino’s earlier challenges. A day before the interview, Donald M. Rothberg of Associated Press quoted Marcos as saying, “Let’s put this to bed. . . I’m glad I was challenged to debate with her.” And with a hint of sarcasm, added “I’m trembling all over because of this debate.”

Held on February 5, the “debate” was a buzzer-beater. The snap election was scheduled on February 7, and the Election Code forbids any type of campaign activity 24 hours prior to the polling day. Marcos opened the interview with an explanation as to why the supposed debate was not held on the 6th, saying he did not want to break the law. To which Koppel responded, “No one has yet explained to us how an interview on American television, not rebroadcasted in the Philippines, could violate any law. Furthermore, we offered to do the broadcast last night [February 4], Mrs. Aquino accepted, President Marcos did not.” Nightline ended up broadcasting two separate, recorded interviews of Marcos and Aquino. During his airtime, Marcos as usual drilled on Cory Aquino’s inexperience.

But the issue of inexperience is hardly the vilest of Marcos’s attacks against Cory. On January 23, 1986, the Associated Pressquoted Marcos as criticizing Aquino for “having the nerve to aspire for the presidency when she knows little about running the country.” Speaking in Filipino, he said that the ideal Filipino woman is “modest, does not challenge men, is intelligent but she keeps it to herself and teaches her husband only in the bedroom.”

Francis X. Clines of the New York Times followed up on this story in his article published a week after. Having no hint of remorse, Marcos complained about being vilified for his sexist remarks. He said, “Of course they belong to the bedroom, but in the sense of a woman’s being discreet. If she had something to say to her husband which might humiliate her husband.” Marcos further professed that Aquino “has not run anything in her life” and would govern the country using “cram courses” and “pious intentions. . . . A family tragedy simply cannot be the justification for leadership or for flirting with national destiny naively or carelessly,” referencing the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983.

The then first lady Imelda Marcos, once touted as Marcos’s “secret weapon” in his previous electoral campaigns, and who held multiple high-ranking government positions, shared her husband’s misogyny and chauvinism. The Los Angeles Times reporter Mark Fineman quoted Imelda saying that Aquino is the “complete opposite of what a woman should be because she is challenging the power of a man.”

The former first lady also managed to criticize Aquino‘s appearance whilst implying the shallowness of an entire community, “[o]ur opponent, she does not wear any makeup. She does not have her fingernails manicured. How else, Imelda wondered, can Aquino capture the large Manila gay vote? You know gays. They are for beauty,” a United Press International report quotes. This is the same Imelda who expressed grave concern that her daughter Imee was hanging out with “faggots” in Princeton University, as revealed in a diplomatic cable from the American Embassy in Manila dated November 4, 1974.

Marcos was indeed fixated on the fact that his opponent is a woman. In a campaign speech in Malolos Bulacan on December 27, 1985 (as transcribed by FBIS), he said:

I have said we are having difficulty because our adversary is a woman. As you know, to me all women are beautiful. So I should say she is beautiful. You can see the dilemma I am in. As I have told some people, I do not know what I should do. If we criticize her, we get attacked; so perhaps it is best not to say anything about her. So you see, we are damned if we do, we are damned if we don’t. In the past it was not so bad. Perhaps I should just keep quiet, but she is the one making all the noises. As you know, I am not used to quarreling with women. I do not like to provoke women.”

Marcos’s (and apparently his running mate Arturo Tolentino’s) bigotry, in full view of the public, only went from bad to worse. So much so that the public information chief of Cory’s Crusader, Narzalina Lim, decried the “blatantly sexist and often obscene language employed [by] the two KBL candidates in their provincial sorties.” She said in a statement quoted in the Manila Times Journal, “[t]he constant harping on the ‘woman on top’ and ‘hamon ng babae’ [challenge of women] theme is an insult to Filipino womanhood worthy only of male chauvinist pigs.”

But for a man who had seemingly infinite ways of insulting women, Marcos appealed to them the only way he knew how: by extolling their good looks and that of his wife. In an FBIS transcript of his campaign rally speech in Iloilo on January 27, Marcos insulted both his opponent’s intelligence and rationality, all the while pandering to the Ilonggo women:

That Cory Aquino is something else, she does not have Ninoy’s intelligence. Look at her, what has she been saying? “The moment I win as president, I will have Marcos arrested”. . . But as you can see I am accompanied by a beautiful woman. I am surprised here in Iloilo—all the women are beautiful. [cheers] All the beautiful women, more so especially the older ones. [laughter]

Juxtaposing women and pitting them against each other was Marcos’s strategy for wooing their votes.

But for Marcos and his campaign machinery, women were not only potential voters who would blush at his flattery. They were also deemed as tools for entertainment. The Associated Press reported on January 23 that “hundreds of bar girls and prostitutes marched through Manila’s red-light district” chanting Marcos’ campaign slogans as they were escorted by a marching band and cops in motorcycles. Several bar operators and employees said they received veiled threats that their licenses would not be renewed if they did not take part in the march, the report added.

The 1986 election was Marcos’s most crucial electoral campaign, and yet he was at his most vulnerable. Among the main issues thrown at Marcos was his failing health and his falsified war records. For someone who has dedicated almost his entire life (and a ton of public funds) creating a myth out of his purported manly prowess and vitality, these two issues might have delivered the worst blows to his public image, and more importantly, his ego. In fact, in the February 5 debate-cum-interview with Ted Koppel, when asked a follow up question regarding his falsified war records, the Filipino dictator snapped. With visible clues of scorn in his face, he said, “now look, I don’t want to talk about this anymore. If you do, I’m gonna walk out.”

This is reminiscent of a recent outburst of our current Commander-in-Chief. In the wake of scathing criticisms on his typhoon response encapsulated by the viral hashtag #NasaanAngPangulo (Where is the president?), Duterte spewed sexist innuendos, lies, and threats towards Vice President Leni Robredo, who was at the time being lauded for her efficient and timely rescue and relief efforts in typhoon-ravaged areas.

In the commemoration rites of another deadly typhoon back in 2016, he teased Robredo about her short skirt, and basically reduced the second highest elected public official to a nice pair of legs.

To soothe their bruised egos when challenged by women in politics, Marcos and Duterte resort to the same crude tools in the machismo bag: patronize and demean their women opponents, beat them back to the home and hearth, toy with them as sex objects. And their daughters are not exempt from their machinations.

With one sexist remark Duterte generated a strand of public opinion that welcomes his daughter’s entry in the presidential derby. That’s not Duterte taking pity on his daughter. Marcos did not shield Imee either, contrary to Imee’s spin. These misogynist fathers were not, in fact, protecting their daughters from the rough and tumble world of politics. They treat their daughters as political merchandise that they can sell to voters to expand their political control.