Originally published by Vera Files on May 24, 2020.

The recent exchange between Sen. Imee Marcos and Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III over Masagana 99 reminded us of the late president’s claim of “success” of his banner program to achieve rice self-sufficiency.

Masagana 99 aimed to increase rice production among Filipino farmers. The program that began in 1973 derived its title from the term “masagana” which means bountiful and 99, referring to the number of sacks (cavans) of rice yielded per hectare of land in every harvest season.

During the May 20 Senate hearing on the government’s response to the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, Dominguez cut short Marcos, chair of the Senate committee on economic affairs, when she started batting for the adoption of a Masagana 99 (M-99) scheme in helping raise farmers’ production.

“I was the Secretary of Agriculture that cleaned up the mess of Masagana 99… that was left by Masagana 99. There were about 800 rural banks that were bankrupted by that program and we had to rescue them. So whether it was a total success or not has to be measured against that,” Dominguez said.

Marcos was caught off guard by the remark. She tried to parry it by insisting that Masagana 99 was a success since it allowed the country to export rice, a claim refuted by Dominguez, saying: “Ah, no. We never exported rice. We never exported rice, Ma’am.”

On May 21, Marcos issued a press release castigating Dominguez: “Shame on you, Secretary Dominguez, give the Filipino farmer some credit! When supported by sound government policy and defended against rampant importation, we can feed ourselves. Give the Filipino farmer a chance!”

A thorough look at the much-hyped Masagana 99 showed that for a brief time after it was launched, the Philippines did become a rice-exporting country—or barely that. But data and studies show that this point of pride for the Marcoses and their supporters was not solely attributable to the Masagana 99 credit program.

Moreover, echoing Dominguez, this “success” came at a significant cost, not only to the government, but also to the farmers that the program supposedly helped. Masagana 99 also had an adverse impact on the environment brought about by its dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

MASAGANA 99

After a series of natural disasters and pest infestations in 1972, the Philippines faced a nationwide rice shortage. This prompted the government to intensify rice production with the Masagana 99 Rice Program. Launched on May 21, 1973, Masagana 99 was a crash program primarily intended to raise the yield of palay crop lands per hectare to 99 cavans, from the then national average of 40 cavans per hectare. Not only did it seek recovery from losses incurred from the previous years of low productivity, it also aimed to scale down importation and eventually achieve rice self-sufficiency in record time.

At the core of Masagana 99 was a package of technology offered to farmers in the form of high-yielding variety (HYV) seeds, herbicides, low-cost fertilizer, and other modern agricultural inputs. The supervised credit scheme, on the other hand, was designed to make sure that the farmers can actually use the recommended technology package provided for by the program. The Central Bank extended subsidized rediscounting facilities to both public and private credit institutions to act as stimuli for banks to channel their loans to the agricultural sector. With reduced cost of borrowing made possible by highly subsidized interest rates, in theory, the farmers could avail themselves of the credit program even without collateral and other standard borrowing requirements.

Masagana 99 had peculiar beginnings. After several futile attempts to ramp up rice production in 1972-1973, a group composed of Peter Smith of Shell Chemical Company, Inocencio Bolo of UP College of Agriculture, and Vernon Eugene Ross of International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) presented a proposal to then Secretary of Agriculture Arturo Tanco Jr. consisting of an “integrated package of technology” which, they claimed, could produce the coveted 99 cavans of rice per hectare, “even on non-irrigated land.” Despite broad skepticism over the soundness of the technology (which was drastically different from traditional methods) and the feasibility of its wide-scale deployment, Tanco went ahead with it as a last-ditch effort. Marcos immediately approved the proposal.

The National Management Committee (NMC) consisting of various government and private agencies was created to implement the program, with the Ministry of Agriculture and the National Food and Agriculture Council coordinating it. The NMC worked alongside technical and information committees, and working under them were coordinators ranging from the regional level down to the level of farmer-cooperators. Provincial governors and municipal mayors were tasked to deliver the required number of beneficiaries from their areas.

The crash program was initially envisioned to run only for a single planting season, from May to October 1973. It initially targeted to benefit 400,000 farmers from 43 selected provinces, and to cover about 600,000 hectares of land. Marcos soon expanded its scope and targets and turned it into a high-priority national program that ran longer than expected, even by the project proponents.

Initial funding for the rice credit program came from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which provided a P 77.5-million loan. The World Bank was also part of the financing scheme. As explained by Mahar Mangahas in a 1974 discussion paper:

“The Central Bank passed the funds on initially through a loan to the (government-owned) Philippine National Bank (PNB) and increased government deposits at the (privately-owned) rural banks. It then provided extensive support through rediscounts of loan papers obtained by the PNB branch banks and the rural banks. Funds flowed at a very fast rate indeed. The banks were apparently under strict orders to fulfill loan quotas and not to worry too much about collateral or documentary requirements. Masagana 99 was launched in May 1973. By July 18 it was reported that P192 million had been lent; three weeks later the figure had become P249 million. Finally, by April 1974, P503 million was reported to have been lent, covering a total of 676,000 hectares, or an average of P745 per hectare.”

The targeted borrowers were farmers of small landholdings (more or less two hectares), of which, according to estimates then, numbered around 1.4 million. Less than half of this number would benefit from Masagana 99. Statistics collated by Emmanuel F. Esguerra in his 1981 paper on Masagana 99 that came out in the Philippine Sociological Review offers a clear picture on how the program played out from 1973 to 1980.

During the very first phase of Masagana 99 (May to October 1973), 402,757 borrowers accounted for a loan total of P 369.5 million. The third phase of Masagana 99 (May to October 1974) had the most number of borrowers at 531,249 for a total loan of P716.1 million. This was not improved upon for the duration of the program. Starting 1975 there was a marked decline in the number of farmers who availed of Masagana 99 loans; by then it was just a little over 100,000. In Masagana 99’s 14th phase (November 1979 to April 1980), the number of borrowers sunk to 54,250. There was also a steady decline in the repayment rate. When Masagana 99 started in 1973, 93.3 percent of the loans were repaid. By 1979, the repayment rate fell to 45.8 percent.

WHAT WENT WRONG

Various sources have highlighted how Masagana 99 was simply unsustainable. One key problem, as alluded to by Dominguez, was rural bank insolvency, a consequence of non-payment by farmer-borrowers of their loans. According to a report of the World Bank, dated May 12, 1983, titled Philippines – Agricultural Credit Sector Review:

“The rice area financed by institutional credit decreased from 920,000 ha (hectares) in 1973/74 to 330,000 ha in 1979/80 or from 79% to about 18% of the total rice area in the respective years. The decline in institutional credit was the result of arrearages under past [Masagana]-99 and other supervised credit subloans which were due to several factors including: natural calamities, inadequate post-harvest storage facilities, marketing problems, unremunerative cost-price relationships, the low priority given by farmers to repaying the Government-backed loans, poor selection of credit risks and the provision of excessive loan amounts. The arrearages disqualified a large number of small farmers from receiving fresh credit and also disqualified many rural banks from receiving rediscounting support from the Central Bank. The accumulated nonrepayments under M-99 amount to about P180 million in PNB and P300 million in rural banks.”

In short, farmer-borrowers were defaulting not only because of production shortfalls caused by the various natural disasters affecting Philippine agriculture in the 1970s and the 1980s, but also because the government was not prudently regulating the loans and providing sufficient mechanisms and inducements for repayment. M-99 became, more or less, a massive dole-out program.

That many were defaulting on M-99 loans was no secret. An article in The Straits Times in Singapore, dated August 25, 1981, noted that Masagana 99 and a similar program for fisherfolk, Biyayang Dagat, were both lacking in funds, with a Philippine government official claiming that the repayment rate for Masagana 99 loans was at 60 percent. Kenneth Smith of the USAID, in his article titled Palay, Policy and Public Administration: The ‘Masagana 99’ Program Revisited, noted that even such repayment rates were distorted, given that whenever a loan was restructured/extended, for “book-keeping purposes. . .the outstanding loan was fully paid up and a new loan agreement was initiated.” Smith also noted that many “uncollectable” M-99 loans were “written off” by lenders, further distorting the actual repayment rate.

A 1978 study by V. Cordova, P. Masicat, and R.W. Herdt for the IRRI found that availing loans from Masagana 99 made no difference in the net returns of farmers.

Overall, according to the May 30, 1991 Staff Appraisal Report of a World Bank-funded Philippine rural finance project, “about 80% of the [Masagana]-99 loans have never been recovered.” Randolph Barker of Cornell University tried to give it a positive twist by saying that it became “income transfer.”

What did all that money do? In his technical assessment of Masagana 99, Smith concluded that the program “was indeed successful in attaining national self-sufficiency in rice production” but “the program’s actual achievements were much more mundane than anticipated, and even this degree of success was more fortuitous than finessed.” Smith further noted that the program’s achievements were due “neither [to] the intensity of technical supervision nor the provision of non-collateral credit.” Instead, it could be attributed to the “expansion of hectarage planted to rice,” not increasing yields to 99 cavans per hectare using new technology.

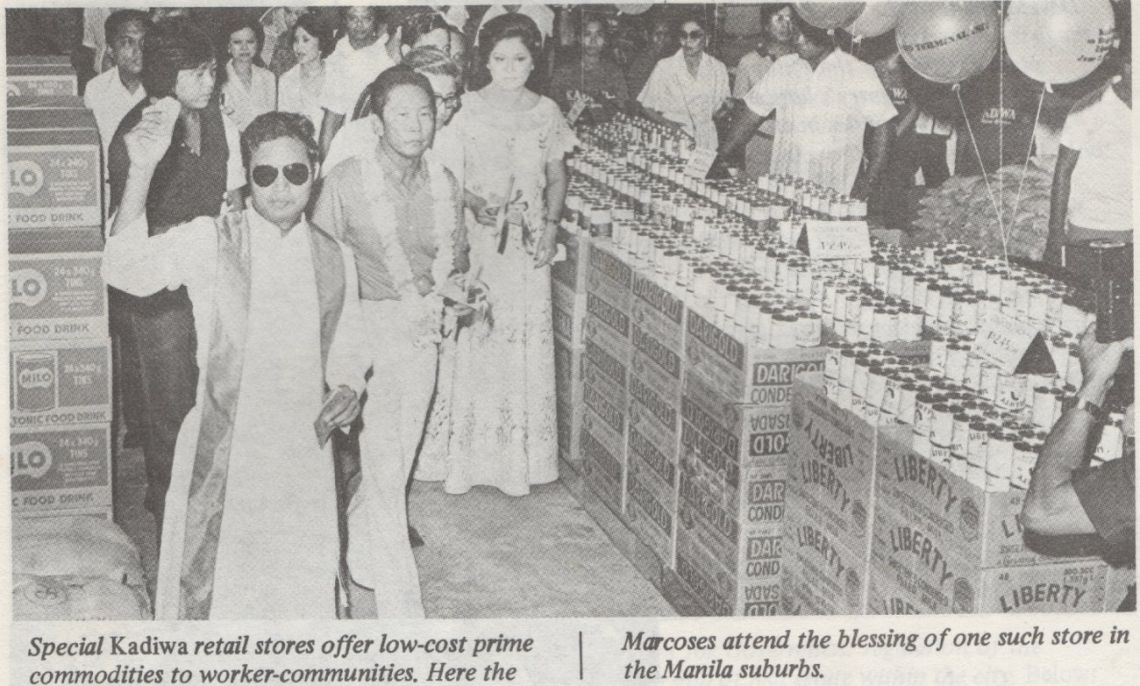

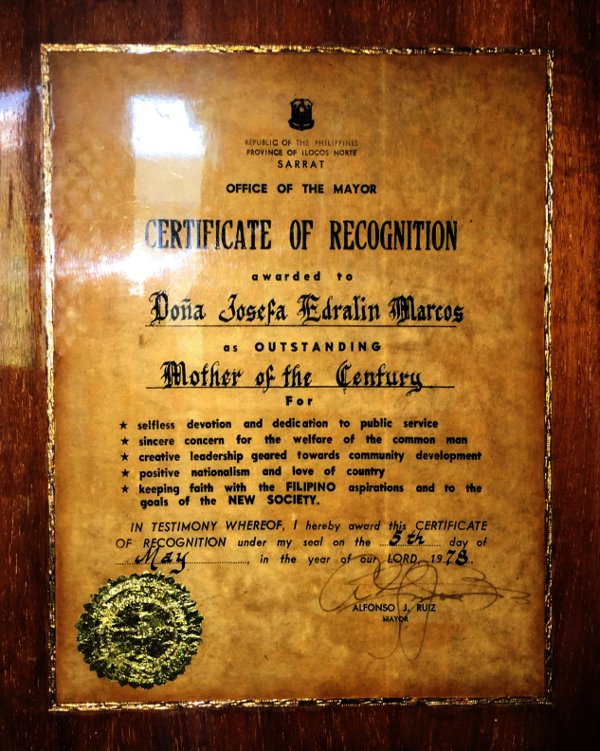

For Emmanuel F. Esguerra, Masagana 99’s importance during the Marcos dictatorship was more political than economic. “[T]he mere existence of a credit program offering low-cost loans to farmers conveniently provides its sponsoring government the means of gaining political and ideological support by publicizing its concern for the rural poor, without necessarily altering the prevailing structure of asset ownership which is the main source of inequality.” There was even a strain of counter-insurgency effort in Masagana 99 as pointed out by Mangahas. “Areas where there is subversion or dissidence are pointedly included, a policy which appears specific to the [Marcos regime, or the so-called] New Society,” he noted.

As it was also a political project, the corruption that it entailed was the cost of doing business for the Marcos dictatorship. National Scientist Gelia Castillo, in a chapter on Masagana 99 in her book How Participatory Is Participatory Development? cited studies and news stories detailing how rural bank officials concocted “fake farmers” and “ghost borrowers” to siphon off millions of pesos intended for Masagana 99. Benedict Kerkvliet, in a 1974 Pacific Affairs article underscored that the “banks remain in the hands of the local elites.” The loss of public funds in Masagana 99 grist the mill of Marcos’s political patronage.

Another poisoned legacy of Masagana 99 that was often overlooked was its deleterious effect on the environment and on traditional agricultural methods. The heavy reliance on pesticides ironically led to pest outbreaks, the absence of one set of predators led to the prevalence of another. Indigenous local flora and fauna were devastated by the use of synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and other chemical components of Masagana 99’s “technological package.”

Reliance on chemical input, in synthetic fertilizer in particular, puts into doubt the claim of Masagana 99 rice self-sufficiency. The dollar supposedly saved from not importing rice just went out another door in importing fertilizer.

Again, despite all of the above, Sen. Marcos insists that Masagana 99 should still be seen as a success because it led to Philippine rice exportation. As detailed by Eduardo Tadem in Grains and Radicalism: The Political Economy of the Rice Industry in the Philippines, 1965-1985, between 1977 and 1983, some 502,000 metric tons of rice were exported by the Philippines. However, citing a previous study by Flordeliza Lantican and Laurian Unnevehr, Tadem gave the following breakdown of that amount, which shows that the volume of rice exported then was not consistent nor particularly high, save between 1979 to1981:

| Crop Year | Metric Tons(1,000) |

| 1967/68 | 40.3 |

| 1968/69 | 0.5 |

| 1977/78 | 13.4 |

| 1978/79 | 38.0 |

| 1979/80 | 236.0 |

| 1980/81 | 175.0 |

| 1981/82 | 11.0 |

| 1982/83 | 29.0 |

The country resumed rice importation in 1984, and ceased to export rice completely in 1985. According to Tadem, by July 1984, the reserve stocks of the country was down to 150,000 tons—sufficient for only 10 days. Thus, the country contracted to import rice from Thailand and China and, later in the year, from Indonesia, which had previously imported rice from the Philippines. In 1985, the Philippines imported a total of 389,654 tons of rice from the United States, Thailand, China, and Indonesia—in what Tadem described as “the highest import level since the ‘miracle rice’ era of IRRI began.”

Moreover, even when the country was still exporting rice, citing data from the National Grains Authority, Tadem said that “because of the corresponding increase in the costs of production brought about by the IRRI technology, Philippine rice had to be sold in the world at a loss. . . from 1977 to 1979, the total value of [the Philippines’s] rice exports reached P590.8 million while the export cost was P665.47 million for a net loss of P74.67 million.” True, the country exported rice, but who benefited?

Farmers bore the brunt of the increasing production costs. According to Tadem, “the irony that most of them bitterly felt was that higher production and yields per hectare did not result in improved real incomes as the increased costs cancelled whatever gains in production was achieved.” Tadem also noted that lower net incomes meant that it became impossible for farmers to repay their Masagana 99 loans. Furthermore, data cited by Tadem from Lantican and Unnevehr shows that real farm wages (farm wage/consumer price index) actually started to decrease within the period when Masagana 99 was being implemented: “From 1972 to 1977, real wages rose from P3.78 to P5.24. However, from 1977 to 1984, real farm wages have declined by 46% [from P5.24 to P2.82].”

The Marcos regime started to lessen reliance on the expensive Masagana 99 program in 1984. In one of his ghostwritten books, The Filipino Ideology, Ferdinand Marcos claimed that a new government initiative, the Intensified Rice Production Program, “was implemented in December 1984 to complement Masagana 99.”

It is perhaps more accurate to call it a last-ditch successor program to address the shortage that Masagana 99 could not. However, IRPP was similar to Masagana 99 in the sense that it did briefly increase rice production, but led to more indebtedness without increasing profits of farmers. According to a 1985 paper by IRRI scientists Bienvenido Juliano and Leonardo Gonzales: “Although the IRPP was launched to provide cheaper credit to rice farmers, the volume of credit it provided and the numbers of farmers covered were less than before.” It meant that “most rice farmers had to pay very high interest rates.” Tadem also explained that since the country had resumed importing rice at the time, the market had become flooded, which kept the price of locally produced rice artificially low, significantly affecting the earnings of the local farmers who were already heavily in debt.

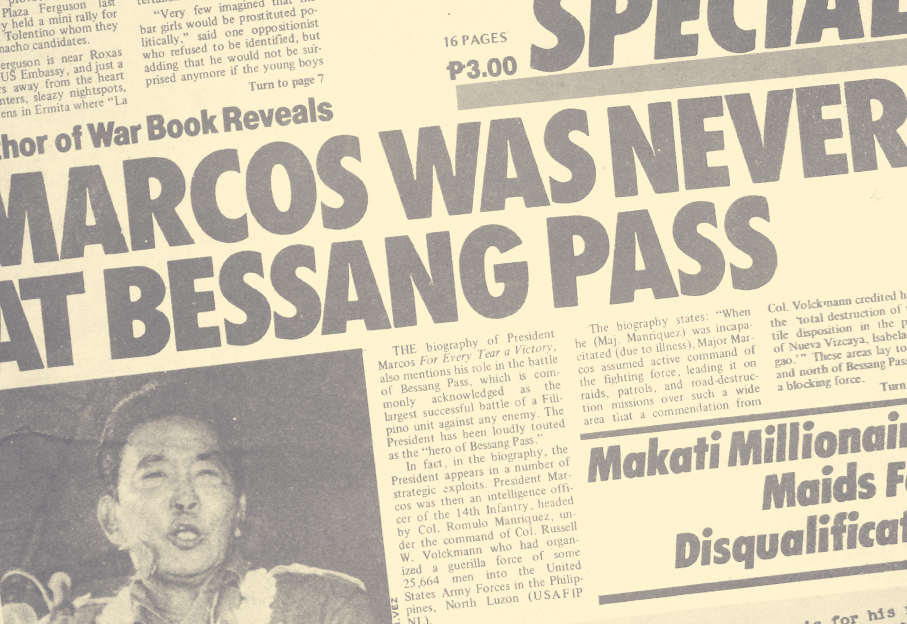

But Marcos continued to tout his administration’s credit programs for rice production during the dying days of his regime. Based on a transcript of a campaign speech he gave in Naga City on January 14, 1986, Marcos told his supporters that in 1967 “we began to export rice to other countries”—failing to mention that the country stopped exporting rice from 1970 to 1977, and again between 1984 and1985. He emphasized that through Masagana 99, “we established a credit system which tries to give capital or operational funds to small tenants and farmers who were allowed to enter banks for the first time in the entire history of the Philippines and without collateral”—masking the fact that many banks and farmers later on found themselves in a worse financial position than before they contracted Masagana 99 loans.

WHY MASAGANA 99 REMAINS A POTENT MARCOS PROPAGANDA

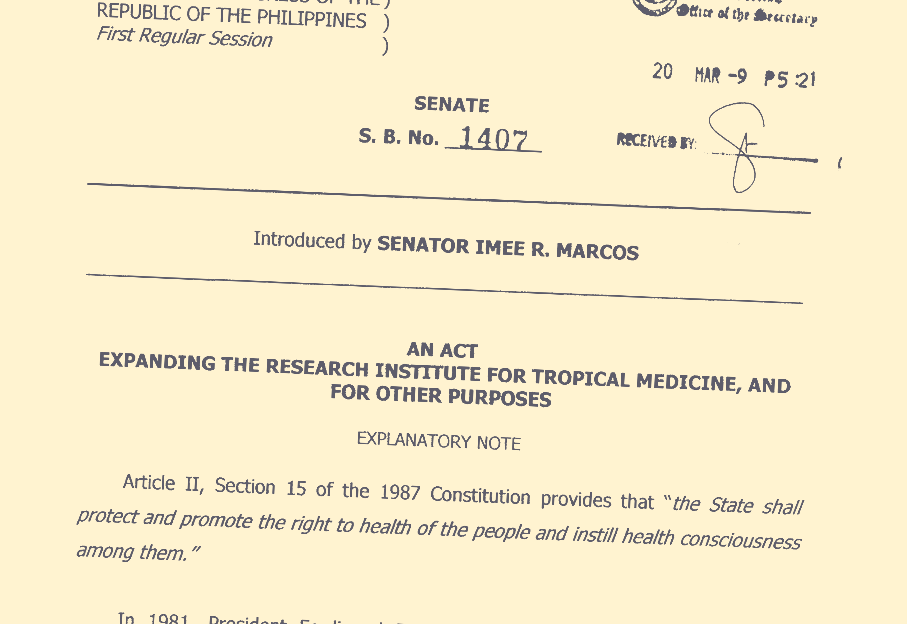

Based on her Facebook page and press releases from her office for her Masagana 99 propaganda in recent years, Imee Marcos consistently relied on the Manila Bulletin column, dated November 5, 2016, titled Masagana 99 Redux, by National Scientist Emil Q. Javier.

An agronomist and plant geneticist, Javier was prompted to write the column after President Rodrigo Duterte said that he wanted to emulate the Marcos-era Masagana 99 and Biyayang Dagat programs. Imee highlights the short sections of Javier’s column where the brief (and qualified) success of Masagana 99 was described. She fails to include the sections where Javier criticizes the program, corroborating much of what was detailed above.

According to Javier: “Sadly, Masagana 99 proved to be short-lived and unsustainable mainly due to the costly subsidies and failure of many farmers-borrowers to repay the loans . . . . By [1980], Masagana 99 ceased to be of consequence as only 3.7 percent of the small rice farmers were able to borrow.”

Javier ultimately does not recommend resurrecting Masagana 99, saying that it will likely result in farmers defaulting on loans again. “Giving away seeds, fertilizers, pesticides and dryers, while politically attractive, is temporary, wasteful and prone to graft,” Javier emphasized. “We have been doing that all these years with little to show for the expense and the effort.”

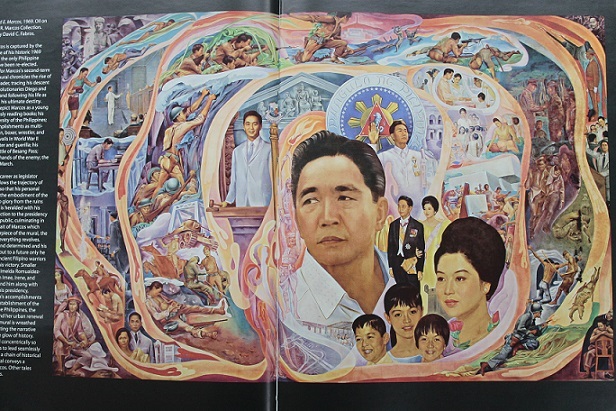

Ferdinand Marcos himself, in the last of the books he purportedly authored, A Trilogy on the Transformation of Philippine Society, discussed only the establishment and initial implementation of Masagana 99, staying silent about its decline and demise in the 1980s, despite the book being published in 1988 and referencing the rice crisis at the time. If this is the kind of “data” Sen. Marcos is relying on, small wonder that she has the audacity to claim that Masagana 99 was an unqualified success.

According to Marcos aide Arturo Aruiza in the book Ferdinand Marcos: Malacanang to Makiki, the late dictator considered the Trilogy to be an unfinished book, hoping that Imee would finish it. Considering how she continues to propagate disinformation about the Marcos regime even during a pandemic—to the point that she is suggesting the revival of a failed program to address our current and upcoming coronavirus-caused economic woes—it seems that she is on track to fulfill her father’s wish.

Masagana 99 shows that the propaganda that comes with doling out patronage proved to be one of the most resilient ways to instill untruth. The lie becomes part of the residual gratitude of those who benefitted from the largesse. Today’s patrons have learned that lesson to perfection. As she ascends greater political heights, Sen.Marcos seems to want to keep on giving away the people’s money the same way her dictator of a father once did.