Originally published by Vera Files on August 30, 2020.

As we celebrate this year’s National Heroes Day, the issue of who should be a hero continues to kindle patches of heated arguments. Or, at the very least, it remains fodder for propagandists wanting to spew rehashed vitriol against one particular member of the pantheon, Ninoy Aquino.

Last August 21 a Twitter hashtag saying that Ninoy is not a hero trended, supposedly shared more than twenty-five thousand times. As declared by Republic Act 9256, signed into law on February 25, 2004 by then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, August 21 is a national special nonworking holiday “to commemorate the death anniversary of former Senator Benigno “Ninoy” S. Aquino, Jr.”

On August 21, 1983, an assassin’s bullet pierced Ninoy’s skull as he stepped out of a plane in the airport that now bears his name. At least for now. The naming of the airport after the slain senator is now the subject of a court petition and a House bill filed last June, both seeking to expunge any association between Ninoy Aquino and the tarmac where he spilled his blood.

The efforts to strip Aquino of his “hero” status are not recent.

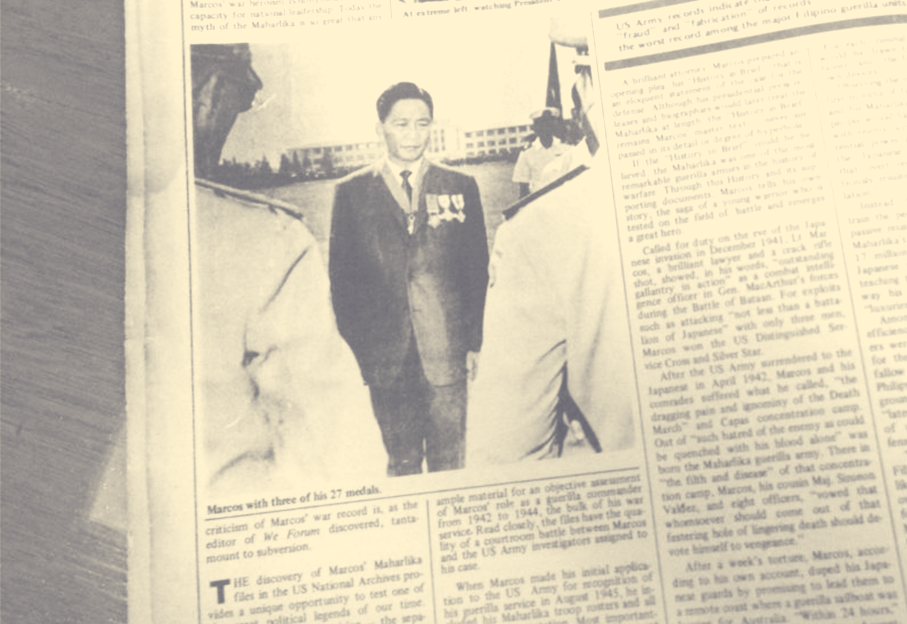

On November 26, 1978, Panorama, the Sunday supplement of Bulletin Today, disappeared from the newsstands. Marcelo B. Soriano in The Quiet Revolt of the Philippine Press mentioned that “more than 300,000 copies of the 68-page magazine for that date were ordered withdrawn from circulation.” The curt explanation given by Bulletin, one of the Marcos-controlled dailies then, was that the copies were recalled “because of printing defects.” But as reported by the Honolulu Advertiser, “Sources said the magazine withdrew the issue from circulation ‘on orders from above’.”

“Orders from above” was executed through a raid conducted by the military at the Bulletin office on Saturday night, November 25, 1978. Writing in the 2019 edition of Press Freedom under Siege: Reportage that Challenged the Marcos Dictatorship, Bill Formoso, then Bulletin’s assistant provincial news editor recalled:

It must have been between 10:00 and 11:00 p.m.when someone ran into the near empty newsroom on the second floor shouting that the military was in the compound. I stood up, turned to the window behind me, and saw that two 6×6 military trucks had entered the compound, stopped in front of the main entrance to the separate printing press building, and soldiers had begun jumping out and running into the building. I knew what they had come for.

For several days, there had been talks that Imelda Marcos was furious over an article in that Panorama issue that was written by Chelo Banal and edited by Letty Jimenez Magsanoc that said that in a university polls of students’ heroes, Ninoy Aquino, who was in jail, had rated higher than Imelda Marcos. We had also heard that copies of Panorama that had already been distributed to subscribers in Parañaque and Las Piñas had been retrieved by soldiers going door to door.

The copies were “impounded and burned,” according to Leonor Aureus Briscoe, when she wrote about this event in Press Freedom Under Siege.

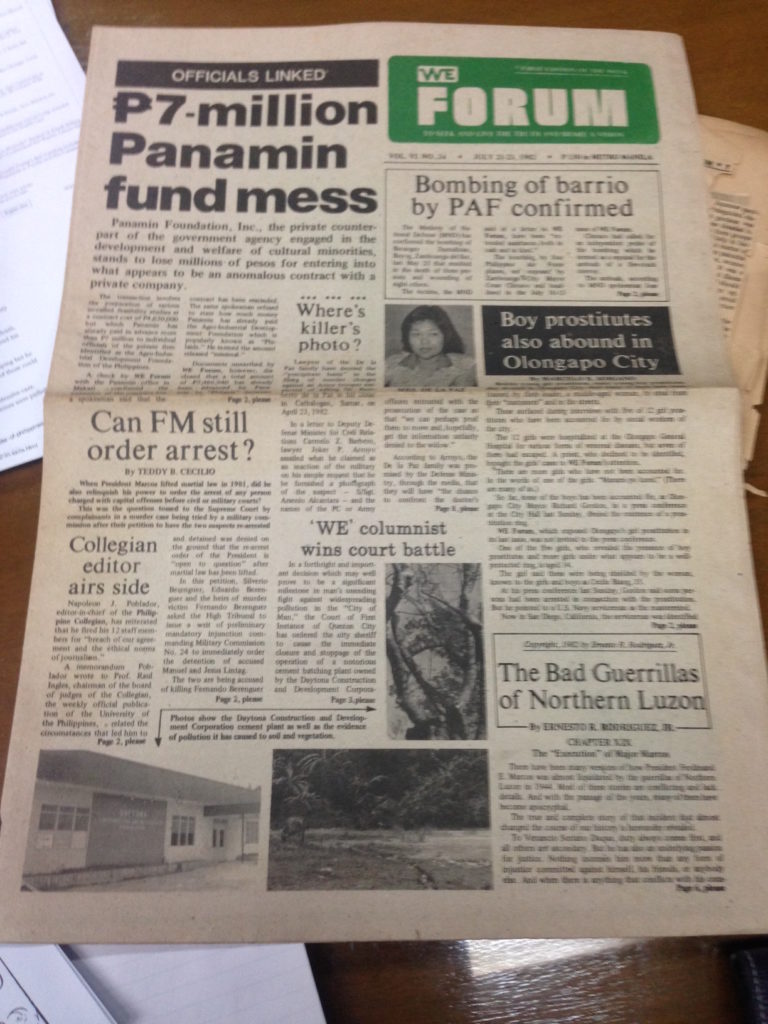

But some copies did survive. We (later on We Forum), in its December 9-15, 1978 issue reproduced the survey and a couple of articles that went with it in the disappeared Panorama issue. (We left out the article “Heroes to Heroes,” an excerpt of which was reprinted in Press Freedom Under Siege.)

Though We was undoubtedly courageous for piercing the censorship, its account of the vanished Panorama made no mention of the raid. Its report hewed to the line that because of printing defects “the magazine was withdrawn by the newspaper management from circulation. Whether the suspension of the distribution was voluntary on the part of the publishers or was influenced by outside forces could not be ascertained.”

But what was it in the survey that forced the hand of those concerned to disappear an entire issue of a magazine?

The Panorama survey that angered Imelda Marcos

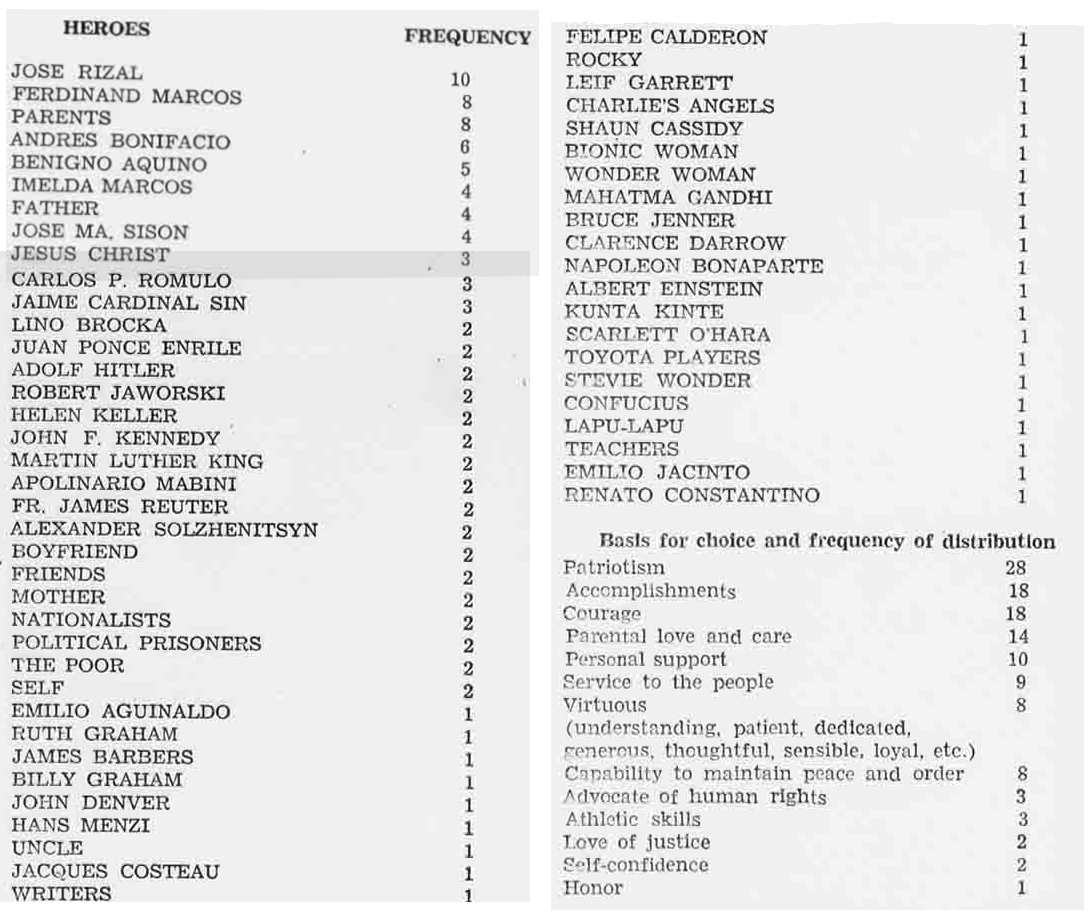

Panorama conducted the survey for its November 26, 1978 special Heroes Day issue. The magazine “polled at random eight colleges and universities in Metro Manila—namely, University of the Philippines, Ateneo de Manila, University of Santo Tomas, De La Salle, University of the East, Assumption, Manuel Luis Quezon University, and Mapua Institute of Technology—to find out who the heroes of today’s college students are and why; a hero to mean anyone, living or dead, who is greatly admired and worthy of emulation. The random survey of 72 students (40 males, 32 females), a representative cross-section of the college student population, yielded a total of 58 heroes.” The heroes were then ranked “according to how often they were named (frequency) and the reasons for their selection.”

Chelo R. Banal, then Panorama staff writer, presented the findings of the survey in the accompanying article “Heroes to Campus Crowd.” In Banal’s short introduction to a reprint of her piece in Press Freedom under Siege, she wrote that “It really started as a harmless little survey but because one of the campuses we tapped was the University of the Philippines, it turned up more interesting results. Malacañang said the survey was biased from the get-go because we knew that UP was the bedrock of activism (at the time, at any time). In that regard, we were guilty as charged. But it was also true that we hadn’t the foggiest who the students would name as their heroes. In fact, Panorama editor Letty Jimenez Magsanoc and I found it hilarious that some students had not understood the context of the survey and named Jesus and Mary as their heroes. Jose Rizal, too. Unfortunately, Ninoy Aquino ranked higher than Imelda Marcos in the survey.”

It appeared that the conjugal dictator then occupying Malacañang can so be easily rattled by what Banal found in the survey as the college students’ “ambivalent attitude toward authorities who have been efficient at maintaining peace and order and those persons who are supposed to have threatened the national security.”

Analyzing the survey, Banal offered the following instances as proof of this ambivalence:

Ferdinand Marcos topped the contemporary heroes, followed by Benigno Aquino Jr, an interesting study of contrasts because the former is the founder and the preserver of the New Society and the latter is believed to be against the present political order.

Of the top four living heroes, two (the President and the First Lady) are prime movers of the New Society while the other two (Benigno Aquino and Jose Ma. Sison) are identified with the opposition. It would seem that students are divided pro and con the validity and achievements of the New Society.

President and PM Marcos was voted the Number One here-and-now hero for being “a revolutionist who uses no arms” and for “sticking his neck out in declaring Martial Law to realize his vision of a disciplined, progressive and truly Filipino society.”

As many students who favored Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile also considered the political detainees their heroes. Even the religious leaders admired—Jaime Cardinal Sin and Fr. James Reuter—are identified with political detainees or known to have sympathies for the detainees’ human rights.

Perhaps the Marcoses saw what then Panorama editor Letty Jimenez Magsanoc saw. In her brief article, “A Question of Heroes” that went with the survey result, Jimenez Magsanoc claimed that the “Panorama‘s random survey on who are the heroes of today’s Filipino college student would seem to indicate in sum, that he is highly politicized.” The ambivalence and almost incongruous choices for a hero is an assertion that “they’re no cultish followers.”

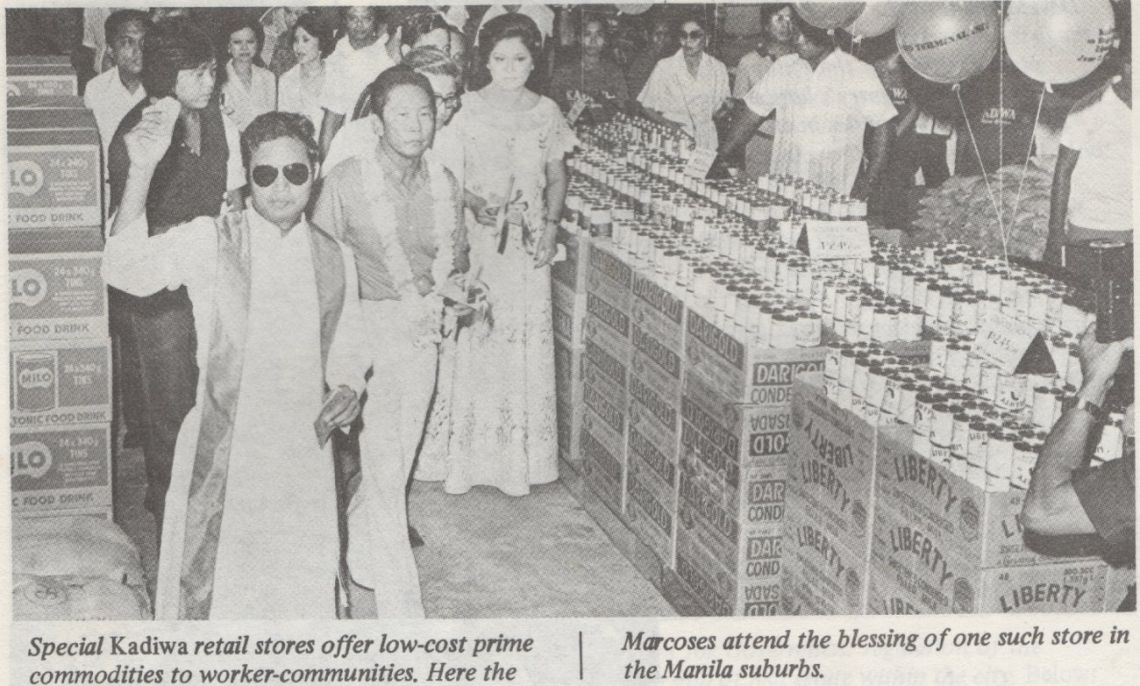

Arguably, for Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos nothing will do but absolute adulation, nothing better than unthinking acquiescence. If those cannot be had they would settle for an overwhelming electoral victory. In April 7 of that year, Marcos’s Kilusang Bagong Lipunan won 187 seats in the elections to the Interim Batasang Pambansa. Only 13 oppositionists won. In Metro Manila, the ticket led by then still in jail Ninoy Aquino were all defeated, 21-0, by the ticket headlined by Imelda Marcos. Notwithstanding that fact that the night before the election Metro Manila erupted in a noise barrage in support of the opposition. The Panorama survey carried a faint echo of this protest. Autocrats, fascists for that matter, desire a populace that will not, or cannot make a distinction except those sanctioned by the dear leader. How dare these college students prefer heroes other than the Marcoses?

The obsession with the absolute courses through the collective memory of the Marcos loyalists, that only the good, the true, and the beautiful Marcoses and their golden autocratic years matter. Yet this unquestioning fealty to the legacy of a dead dictator comes with a suppurating insecurity that every now and again the Marcos loyalists would whisk and fling all over, poisoning the public discourse on heroes and heroism. If Marcos cannot be great again, no one else should be.

The core argument of those vituperating against Ninoy is this: he came home in pursuit of his presidential ambition fully aware of its possible fatal consequence. He sought martyrdom for political effect. The sinister implication is that harboring a political ambition not in the interest of those in power is reason enough for them to do you in. It is not so much a denigration of a person’s sacrifice for freedom as much as a justification for murder.

With imprisonment and a muzzled press, Marcos tried then to deny Ninoy public honor, sympathy, and recognition. Marcos is gone but he is not lacking of supporters to continue his vicious pursuit.