Originally published by Vera Files on September 22, 2020.

High noon of June 30, 1981, the sound of “And he shall reign forever and ever” from Handel’s Messiah soared over the crowd that gathered at the Rizal Park and into the homes of Filipinos all over the country, glued to their TV sets or listening to the radio.

The occasion was the third inauguration of Ferdinand E. Marcos as president of the Republic of the Philippines.

Elected president in 1965, reelected in 1969, dictator from 1972 until 1981, Marcos by then seemed indeed poised to be the eternal ruler, or a “secular messiah” as Raymond Bonner put it in Waltzing with a Dictator. And in Ferdinand’s own estimation he almost was.

Writing in his diary on September 22, 1973, a year after declaring martial law, he believed that “there must be a Guiding Hand above who has forgiven me my sins…and led me to my destiny. Because all the well-nigh impossible accomplishments have seemed to be natural and foreordained. And into the role of supposed hero in battle, top scholar, President I seemed to have gracefully moved into without the awkwardness of pushiness and over anxiety.” Marcos’s diaries are peppered with such musings.

Alexander R. Magno, writing in Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People, included Imelda, consort to the demigod Ferdinand, as the other half of the semidivine duo that also demanded veneration. “Aside from vesting all power in himself, Marcos also tried consciously to build a personality cult around himself and his wife, who began to assume a mythic aura.”

As they were the Malakas and Maganda that gave birth to the New Society, worship must be given unto them on holy days. Ferdinand’s birthday, September 11, became Barangay Day while Imelda’s birthday, July 2, became Working Women’s Day via presidential proclamations.

Then there was, of course, Marcos’ designation in 1973 of September 21, his desired date for the declaration of martial law in 1972 (though it was declared to the public on September 23), as National Thanksgiving Day. He later declared the date a special public holiday, claiming the Association of Barrio Captains requested it in a formal resolution. Why insist on September 21? Ferdinand was fixated with number seven and numbers divisible by seven as harbinger of personal luck.

Barangay Day was a holiday from 1975 until 1985. Marcos issued Proclamation No. 1490 on August 26, 1975, declaring his birthday as “Araw ng mga Barangay sa Pilipinas. In the proclamation, he claimed that it was the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Barangay that “requested that September 11 be set aside to commemorate the institution of barangays in the Philippines.” Two days before the first Barangay Day, Marcos issued Proclamation No. 1495, making September 11, 1975 into a Special Barangay Day, which enjoined “all citizens of the country both public and private to render civic action work during their off-hours.”

An attempt in 1985 to remove both September 11 and September 21 as national holidays was made by Eva Estrada Kalaw in her capacity as an elected member of the Regular Batasan Pambansa. Nothing came of Kalaw’s bill, what with two-thirds of parliament siding with the administration.

July 2 became Working Women’s Day in the Philippines via Proclamation No. 1984, issued by Marcos on June 27, 1980. The proclamation does not explain why July 2 was chosen, stating that all residents of the country should “celebrate this day appropriately in recognition of the contribution of the working women to nation-building.”

The last Marcos issuance declaring both September 11 and 21 as national holidays was finally repealed on September 10, 1986 by Memorandum Order No. 35 authorized by President Corazon Aquino.

Cover of a specially printed souvenir program of the Armed Forces of the Philippines’s Loyalty Day, September 10, 1976.

ON THE BIRTHDAYS OF DICTATORS AND DEMIGODS

If only the birthdays of Ferdinand and Imelda were just that—a blotch in the calendar. But in furthering their control of the country under martial law, first they turned them into state affairs, then into a tawdry spectacle of power and caprice. At which point, they have invited not only resentment but active opposition from the people, some of which were deadly enough to rattle the conjugal dictatorship.

The impulse for the ostentatious was there early on in the Marcos couple. Halfway into Ferdinand’s first presidency, James Hamilton-Paterson in America’s Boy cited a letter by then United Kingdom ambassador to Manila, John Addis, expressing relief that his “trip to Tacloban to celebrate the First Lady’s birthday was cancelled.” Addis, continued Hamilton-Paterson, has the press people to thank, “that it was newspaper criticism that had caused the cancellation of Imelda’s birthday celebrations in 1967 indicated a growing opposition to her extravagant style.”

Any pretense to propriety vanished with the dawning of the martial law’s New Society. Once a close aide of the president, Primitivo Mijares in The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, made the assessment that “Philippine media have virtually nothing but praise for the Marcos martial regime and the wealth and beauty of Imelda Marcos. On such occasions as his or her birthday, or anniversary of the martial regime or of their wedding, the praise for Ferdinand and Imelda becomes almost hero worship.”

Beth Day Romulo, wife of Ferdinand’s secretary of foreign affairs Carlos P. Romulo, was part of the couple’s inner circle, one of Imelda’s Blue Ladies. In Inside the Palace: The Rise and Fall of Ferdinand & Imelda Marcos, she described what these birthdays were like.

“On the President’s birthday each September,” Day Romulo wrote, “we either flew to Sarrat for an all-day fiesta or attended a luncheon at Malacañang Palace that lasted at least four hours. All of his Cabinet and all of the generals and their wives were required to perform in his honor.” When it was Imelda’s turn in July, “we flew down to her beachside palace at Olot (in Leyte province, near where she was born) for a long, lavish weekend of beautiful girls, models, dancers, musicians, flowers, and fashion shows. Of the several sitting rooms, there was one—off limits to most of the guests except Imelda’s Blue Ladies—where caviar and champagne were served round the clock.”

Both Ferdinand and Imelda had a taste for the profligate and the frivolous, and even the grotesque. Ferdinand wrote in his diary that a night before his birthday, September 10, 1973, generals of the Armed Forces of the Philippines hosted a dinner in his honor. There was a fashion show of sorts aping Imelda’s then initiative to showcase works of Filipino fashion designers, the Bagong Anyo. The generals paraded themselves in drag. “They looked so credible—a[s] streetwalkers,” an apparently delighted Marcos wrote. So delighted that he “pounded the table to splinters from hilarity!” In his memoir, Juan Ponce Enrile recalled a similar performance by military officers at a Malacañang event also attended by the diplomatic corps.

For his actual birthday, Marcos mentioned that the theme was “austerity, no frivolity.” Just an ecumenical mass and a reception for his well-wishers. Yet he ended up receiving a bronze bust from University of the Philippines president SP Lopez and his birthday capped by a variety show, “Alay ng Bayan” at the Rizal Park where “about 500 movie, TV and radio stars” performed and was seen on TV “by a million and a half people.”

But any tribute from the people paled in comparison to what Imelda and Ferdinand gave each other during their birthdays. Hamilton-Paterson tells it best in America’s Boy:

An interesting after-effect of the Dovie Beams affair was that of making amends by public works. Ferdinand had already claimed to have built the San Juanico Bridge between Samar and Leyte (Imelda’s home province) for his wife. Certainly the public billet-doux Ferdinand attached to it was ‘A Birthday Gift to Imelda the Fabulous by the President’, even though such a road link was a vital part of the nation’s Pan-Pacific Highway running the length of the archipelago. From now on the Marcoses began to play out their marital tiffs by means of public monuments . . . Their ingenious tastelessness embraced the Philippine nation as an extension of the First Family, assuring the children that Daddy and Mommy loved each other very, very much, and this was one family that would never break up.”

Ferdinand gifting Imelda the San Juanico bridge was hard to top. Though Imelda may have started this act of appropriating government infrastructure projects as her own gift to bestow when she opened the Cultural Center of the Philippines on September 10, 1969, eve of Ferdinand’s birthday.

One can argue that the Marcoses pilfering public edifices as their gifts to each other can be said to be more symbolic than actual theft. For the actual theft and corruption of public funds, one must look into a private property they have developed to enjoy their birthdays, especially that of Imelda. In this regard, Mijares offered a damning exposé.

In a memorandum that Mijares submitted to the US Congress on June 17, 1975 as part of his testimony on the profligacy and licentiousness of the conjugal dictators (a term coined by Mijares), he made the following claim:

A glaring example of the misuse of US aid is the case of the Hercules C-130 cargo plane given by the USAF to the Philippine Air Force. Hardly had it been turned over, when the provincial resthouse of the Marcoses in Barrio Olot, Tolosa, Leyte province, was burned down by disgruntled barrio folks. Among those who set the sprawling resthouse afire were people who were practically evicted from their small lots which surround the Olot resthouse; their properties were forcibly purchased from them so the vacation compound could be expanded. The compound was burned down in late May. Since the birthday celebration of the First Lady (on July 2, 1974) was just a month away, the resthouse had to be reconstructed at all cost; Mrs. Marcos has already invited her international jetset friends, headed by Mrs. Christina Ford. So, construction materials, (e.g. cement, hollow blocks, and lumber, etc.) were airlifted from Manila to Tacloban City, which was the nearest airport to Barrio Olot, by Philippine Air Force planes, mainly the C-130 Hercules plane, in order to complete construction of the destroyed area on time for the birthday bash.

Imelda’s Olot resthouse, as described by Beth Day Romulo, had “three heliports, two Olympic-size swimming pools, an auditorium, a chapel, and an 18-hole golf course. Besides the big main house, with its dining room overlooking the sea, there was a string of connected guest suites, individual beach houses, and guest cabanas. There was also a huge flood-lit outdoor pelota court with bleachers for the onlookers.

She continued: “By the time Imelda’s birthday arrived in July of 1974, she had gathered a collection of guests: Van Cliburn and his mother, Cristina Ford, the Italian actress Virna Lisi, and thirty other Italians whom Cristina had brought along for the partying. The entire diplomatic corps had also been invited, plus the Cabinet members and their wives and a goodly splash of generals. (Imelda, like her husband, believed in keeping in close touch with the military—they could make the difference as to whether you kept your throne or not.) There must have been a thousand people at Imelda’s little resort that year.”

How to feed them? Mijares, in his book, reproduced a January 23, 1975 Philippine News interview with Don Eugenio Lopez, from whom Ferdinand took Meralco under duress in his so-called attempt to break the old oligarchy. As per Lopez: “An article last week by your business editor, Mr. L. Quintana, mentioned the fact that during the birthday party of Mrs. Marcos last July 2, 1974, all of the catering personnel of the Meralco employees’ restaurant and cafeteria, together with most of the restaurant facilities (silverware, glassware, china, etc.) were flown to Leyte Island to serve the personal guests of Mrs. Marcos. Also the Meralco planes were used continuously to transport many of Mrs. Marcos’ invited guests. Marcos’ guests.”

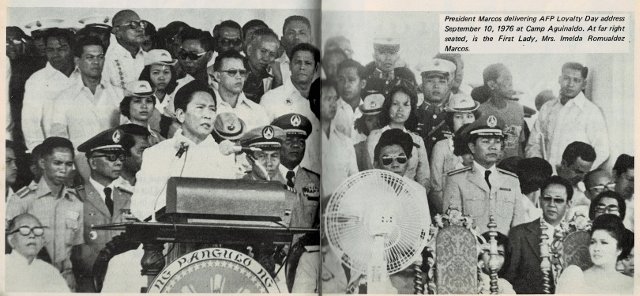

When it was Ferdinand’s turn to celebrate his birthday in 1974 he was Caesar. During his dictatorial reign, it was customary for the AFP to hold a “Loyalty Day” for their commander- in – chief a day before his birthday. Usually, this involved a parade and review in Camp Aguinaldo, a symbolic flyover from the Air Force, and a speech from the president. In 1974 though, Agence France-Presse reported that not only was his speech nationally televised, the AFP officers and men made a pledge of loyalty to him as commander in chief.

On his birthday, Ferdinand was extracting pledges of loyalty from another group of men, political prisoners that he rounded up and jailed when he declared martial law. There were about 5,000 of them then. He released five as an act of “executive clemency.” Provided, however, that these men, as Agence France-Presse reported, “sign a pledge of ‘loyalty’ to the republic and to the new constitution which Mr. Marcos had declared as ‘ratified’ after a martial law-style referendum last year.” The most prominent of those released was Sen. Jose W. Diokno.

Ferdinand jailed Diokno as martial law was declared. For two years, a long stretch of which he was in solitary confinement, no charge was ever brought against him nor was he ever brought to trial. Diokno’s family filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus before the Supreme Court. The High Court, packed with Marcos appointees, never took it up.

To be given clemency by the dictator presupposes that those who were pardoned committed a crime. In Diokno’s case, he was not found guilty of any. On top of signing a loyalty oath, Agence France-Presse said that “he was made to sign another paper in which he acknowledged that he had been accorded fair treatment during detention.” Diokno made written reservations to both. Marcos Caesar not only humiliated his political enemies, he made them complicit in a lie.

As with the AFP Loyalty Day, Ferdinand claimed the following year and the years after that, as reported by foreign news services, that granting “executive clemency” and commuting sentences—which became a toss-up between political detainees and common criminals—was by then in keeping with his “birthday tradition.”

Ferdinand invented other “traditions” around his birthday, all for political effect. On September 13, 1976, the Associated Press reported that Marcos and his family celebrated his 59th birthday with villagers in the central Philippines, which the government release said ‘is in keeping with a tradition for the president to spend his birthday with the barrio people’.”

When he turned 60, another “tradition” surfaced. United Press International reported on September 12, 1977 that “Marcos drove to his hometown of Batac…to fulfill a tradition which calls for a person born in the region to return on his 60th birthday.” It added: “Top government and military officials and members of the diplomatic community went to Batac for the occasion. They participated in a motorcade that began two days ago on MacArthur highway, which was lined with Filipinos, some of whom stood in the rain for hours.”

William H. Sullivan, then US ambassador to the Philippines, in a September 12, 1975 cable to the US State Department called them “heavily publicized pilgrimage to [the] countryside.”

Ferdinand’s pilgrimage ended in 1978. On September 14, a Philippine Air Force plane carrying government officials and reporters on their way home from attending the president’s birthday bash in Batac crashed in Paranaque. Thirty-two were killed. Ferdinand and his family drove back to Manila on September 15.

Marcos himself had no qualms appropriating big-ticket government projects as “birthday greetings” for himself. On the eve of his birthday in 1984, he attended the inaugurations of the Mak-Ban III and Calaca power plants and the first Manila Light Rail Transit line. He stated his belief that the inauguration of these power plants “is the National Power Corporation’s special way of greeting the president a happy birthday.” As for the LRT, after giving his address, Marcos went to the driver’s seat of one train, and took it for a test run. Rides in the still-unfinished line, were free for the next three days.

The urge to propitiate Ferdinand or Imelda on their birthdays was almost an instinct to some people then. In 1984, Imelda was called to testify before the Agrava Commission on what she knew about the assassination of Ninoy Aquino. She showed up on her birthday. When she was done, the board investigating the death of Ferdinand’s chief political rival sang “Happy Birthday” to Imelda.

This gesture is similar to the one made by the Supreme Court when it delivered a decision perfectly timed to coincide with the president’s birthday. The September 12, 1985 issue of Pacific Daily News noted that “the Philippine Supreme Court Wednesday upheld the National Assembly’s decision last month to kill the opposition’s move to initiate impeachment proceedings against President Ferdinand Marcos. The ruling came as Marcos celebrated his 68th birthday.”

Ferdinand twice wielded his birthday as a political tool to directly ward off the opposition. In 1979, there was a strong call for the lifting of martial law. Ferdinand had his birthday celebrated in the Rizal Park, with Cardinal Sin saying the mass. He gathered almost a million people, though the United Press International in a September 12 report observed most of those in the crowd were civil servants and students required to attend, and that buses and jeeps were used to haul people from nearby provinces. Ferdinand did a paper lifting of martial law in 1981.

From the Armed Forces of the Philippines’s Loyalty Day souvenir program, September 10, 1976.

OLD TRICKS NO LONGER WORKED

With the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983 galvanizing the opposition, Ferdinand tried to use his 68th birthday in 1985 to call for national reconciliation. The formula for the 1979 gathering did not seem to work. The million was then reduced to 50,000 in 1985.

When Ferdinand and Imelda turned their birthdays as days of historical import in the life of the nation, as days when they can extract obedience and gratitude from the people, they have also opened the calendar to the wary hands of those who were unwilling to be daunted by the dictatorship. Those hands circled the Marcoses’ birthdays red and bided their time to dissent.

In the early years of the dictatorship, with a controlled press and the opposition silenced, Imelda expected no criticism of her extravagance. But the people noticed. “A more pointed slight had come on her forty-fifth birthday, in 1974,” wrote the journalist Katherine W. Ellison in Imelda: Steel Butterfly of the Philippines, when three university students staged “The Coffin of Cinderella.” The play was about the rise and fall of a character clearly recognizable as Imelda – raised from poverty by a handsome prince that she killed when he stood on her way, and who was chased off her throne by her indignant subjects. Police closed down the play after three wild performances, and the writers went into hiding, Ellison wrote.

On her birthday in 1980, it was the jeepney drivers that refused to give Imelda her day. The July 3, 1980 issue of the Honolulu Advertiser reported that “about 10,000 commuters were stranded because jeepney drivers refused to join the festivities and provide free rides. They said gasoline was too expensive.”

The urban insurgency that flared up in the early 1980s led by the April 6 Liberation Movement once did their bombing campaign to coincide with Ferdinand’s birthday. A grenade exploded in a vacant lot near Silahis Hotel in Malate killing two women and wounding 25 other people on Ferdinand’s 65th birthday in 1982.

On Ferdinand’s birthday in 1983, held less than a month after the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, the Catholic Church and Ninoy’s widow, Cory, pushed for a general amnesty for political prisoners. Ferdinand ignored the call for a general amnesty and released 37 political prisoners. Jaime Cardinal Sin, archbishop of Manila, considered it a “positive first step” but insisted that more than 500 political detainees remain in jail, according to a September 12, 1983 Associated Press report. The following year Cardinal Sin refused to hold a mass in Rizal Park in honor of President Marcos’ birthday.

In 1984, while Ferdinand was playing LRT driver, “anti-Marcos activists were cheered by thousands as they began a protest march. About 250 protesters escorted two statues of opposition leader Benigno Aquino on the start of a planned march from the airport where he was assassinated last year to his home province 78 miles away. Some of the protesters used their teeth to rip apart cloth signs hanging along the way wishing Marcos a happy birthday,” reported David Briscoe of the Associated Press on September 12, 1984.

On Imelda’s birthday on July 4, 1985, United Press International reported that “about 500 priests, nuns and pastors marched near the presidential palace Tuesday to protest alleged government persecution and the recent killings of several church workers….One priest noted that it was first lady Imelda Marcos’ 56th birthday and said he wanted to present the coffin as a gift to the ‘two crocodiles in the palace’.”

And while Ferdinand and Cardinal Sin were talking of national reconciliation in a mass at the Rizal Park celebrating the former’s birthday in 1985, “about 500 students marched to Marcos’ palace,” Associated Press reported that day, “and set fire to what they said was their birthday gift to him—a cardboard coffin marked ‘Death to the Dictator’.”

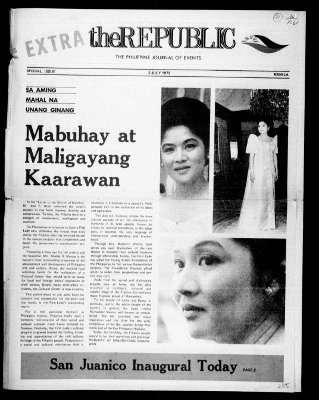

Cover of the special issue of The Republic solely devoted to celebrating Imelda Marcos’s birthday in 1973.

LEGISLATED LEGACY

Around twenty years after the last celebration of Barangay Day and National Thanksgiving Day, a significant attempt to restore September 11 as a legislated holiday was initiated with the filing of HB 4592 on August 3, 2005 by Ilocos Norte first district representative Roque Ablan Jr, It was unanimously approved by the House on third reading three months later, but it did not prosper in the Senate.

The 2005 Marcos Day bill was one of dozens of local holiday bills tackled by the Senate in late 2006 up to June 2007. Only thirteen of these bills became laws. The Marcos Day bill was apparently given low priority since Ilocos Norte already had one legislated holiday and senators were concerned over potential economic losses if a locality has too many non-working days.

Before Marcos’ 91st birthday in 2008, Executive Secretary Eduardo Ermita, by authority of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, issued Proclamation No. 1604, declaring September 11, 2008 a special non-working day in Ilocos Norte.

In August 2016, the Ilocos Norte Provincial Board passed a resolution urging then newly elected president Rodrigo Duterte to declare September 11 of that year as President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Day. Duterte did not oblige. Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, by authority of Duterte, did make Marcos’s birth centennial a special non-working holiday in Ilocos Norte via Proclamation 310, signed September 4, 2017. The proclamation noted that “the Ilocano community has been annually celebrating the birthdate of the late Ferdinand E. Marcos, and commemorating his life and contributions to national development as a World War II veteran, distinguished legislator, and former president

In 2016, Ilocos Norte first district representative Rodolfo Fariñas, along with 26 other lawmakers filed HB 2615, made another attempt to declare September 11 of every year as a holiday in Ilocos Norte. Similar to what happened in 2005, the bill was approved in the House but it died in the Senate.

On Sept, 2, 2020, the House of Representatives approved House Bill 7137 declaring September 11 as “President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Day” in Ilocos Norte. One of the authors of the bill, Ilocos Norte 2nd District Rep. Angelo Marcos Barba, said the bill “will afford us Ilocos Norteños a day to fully celebrate [Ferdinand Marcos’] birthday, honor his greatness, his brilliance, his legacies to us and to the nation as a whole.”

LOCAL HOSANNAS

Memorials to Ferdinand Marcos litter Ilocos Norte. In 2017, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines turned over a historical marker to Ilocos Norte to commemorate Ferdinand Marcos’s birth centennial. The marker is now in the pedestal of the Marcos monument in Batac, close to the Marcos Presidential Center.

There’s also gilded statue of Ferdinand Marcos in Sarrat, near another museum marketed as Marcos’s birthplace. The welcome arch of Sarrat proudly states that the town is the “Birthplace of Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos, 1965-1986.” In the Heroes Walk in Laoag, a bust of Marcos is among other famous Ilocanos. Heading to Paoay, one will see the Malacañang of the North, which is filled with portraits of the Marcoses.

The museums and monuments underwent significant rehabilitation or were put up during the nine-year governorship of Imee Marcos (2010-2019). It was also during that period that the commemoration of Ferdinand Marcos’s birth in Ilocos Norte was revitalized as a major youth-oriented event, dubbed “Marcos Fiesta.” Activities include concerts, art and literary competitions highlighting achievements of the Marcos administration, and a Little Ferdie and Imelda duet competition.

Under the governorship of Imee’s son, Matthew Marcos Manotoc, the tradition of paying homage to Ferdinand Marcos continues. Covid-19 was not a hindrance to the propagation of the myth of Ferdinand Marcos. The young governor, not yet born during his grandparents “glory days,” exhorted his constituents to remind themselves “that our country owes a great deal to President Marcos. We certainly would not be where we are today without him.”