If her “opposition” to her brother is simply an expression of sisterly concern, beyond the recently concluded elections, what will Imee do if helping the Dutertes greatly harms her brother, or her family’s reputation, which she has labored for decades to rehabilitate?

Following the 2025 polls, it appears that Imee Marcos will retain her Senate seat, which means that she has still not lost an election since she first ran for public office in 1984—a feat her father, mother, and brother failed to achieve.

However, based on partial and unofficial results, she is last among the winning twelve senatorial candidates, and she received millions of votes less in this election than in 2019, when she won her first term. A win is a win, one might say. Moreover, she will continue to be a person of influence and consequence in the ongoing conflict between her kin—headed by her brother, Bongbong Marcos, the president—and the Dutertes, principally represented by former president Rodrigo Duterte, currently an inmate at the International Criminal Court (ICC) detention center in The Hague, and Vice President Sara Duterte.

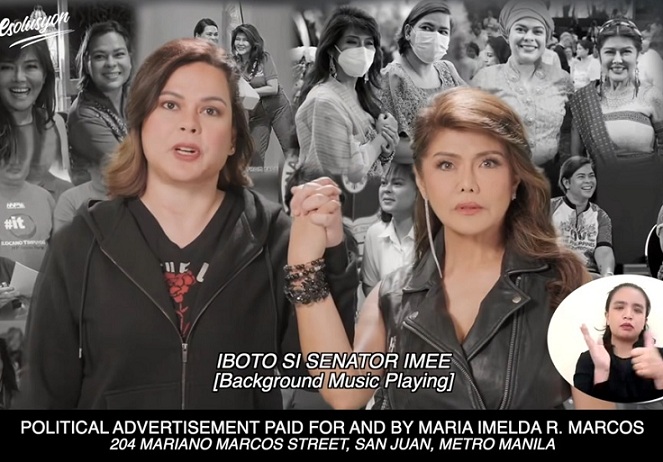

Arguably, Imee would have lost the election if not for Sara’s eleventh hour endorsement of her candidacy. Six months back, she declared herself independent from her brother’s senate slate, but still joined a number of Alyansa sorties when the official campaign season started in February 2025.

Can she really break away from her brother? A Vera Files article has listed the various ways she had differed in opinion with, if not outright contradicted, her presidential ading. However, at the Alyansa kickoff rally in Laoag, Ilocos Norte, held on Feb. 11, speaking in Ilocano, Imee proudly traced back her family’s public service lineage to her grandfather, former Ilocos Norte diputado Mariano R. Marcos, and stretched it up to her son, governor Matthew Marcos Manotoc, and Bongbong’s son, Representative Sandro Marcos. She emphasized that she and her brother were Marcoses, thanking the crowd for their support then, now, and, implicitly, forever; “Marcos latta”—Marcos pa rin, Marcos still, she said.

Looking back at her history as a candidate for public office, we see that Imee tends to prioritize the wishes and whims of her family first to determine her political direction. This history may give clues about where Imee will go following her hairline win, even if that win came as a result of siding with an opposing political dynasty.

During the dictatorship

Before 1984, despite having many appointments in government, most prominently as head of the Kabataang Barangay Foundation, Inc., Imee repeatedly said that she will not run for public office, or words to that effect. Seemingly supporting her stance, as reported in the February 8-9 issue of Ang Pahayagang Malaya, Ferdinand Sr. told newsmen that the administration’s Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) party “will not allow the relatives of incumbent Batasan Pambansa members and local government officials to run in the May 14 [1984] elections ‘unless there is no other alternative’ to prevent the establishment of political dynasties.” He noted that his children were being courted to run by party leaders, but Irene was underaged, Imee “does not want to enter politics,” and he had “discouraged” Bongbong, then governor of Ilocos Norte, from gunning for a seat in the Assembly.

A little over a month later, the Agence France-Presse reported that President Marcos had “turned down many popular petitions for his daughter Imee, his eldest child, and Ferdinand Jr., governor of Ilocos Norte Province, to be KBL candidates in the May 14 polls.”

But AFP noted a shift a few days later: sources from the KBL said Imee had “succumbed to pressures from supporters, specially from her Kabataang Barangay (National Youth) people.” Thus, a short time after Ferdinand Sr. claimed that he was opposed to political dynasties, Imee ran to be a representative of Ilocos Norte at the Regular Batasang Pambansa.

According to a UPI report published in Pacific Daily News on March 30, 1984, citing Deputy Prime Minister Jose Roño, Imee’s father asked her to run “to head off a ‘bloody’ feud between Marcos’ uncle and nephew who both wanted the slot on the ticket.” It is unclear who the nephew was, but the uncle was likely Simeon Marcos Valdez, another Ilocano politician-cum-war veteran like Ferdinand Sr. Apparently, Bongbong had been asked to run for the seat first, but he declined. Both Imee and Bongbong were, of course, members of KBL.

Reluctant candidate though she supposedly was, Imee won, becoming a member of parliament, chairing the Batasan’s Committee on Youth. Within her first year as an unremarkable MP, she was quoted as saying that her father should step down after his current term. According to an Agence France-Presse report, published in various newspapers, including the South China Morning Post and the Straits Times in December 1984, Imee said that “her father’s announcement that he would run again in 1987 was ‘an uncharitable decision’”; “‘I don’t think he’s aware sometimes he has a family,’” she added. Come the 1986 snap election, however, she fully supported her father’s reelection bid.

The documentary titled People Power: The Filipino Experience has footage of Imee campaigning for her father’s fourth reelection. She implied that even she was more qualified to be president than her father’s rival, “mere housewife” Corazon Aquino: “Hindi kailanman humawak ng anumang tungkulin sa bayan. Kahit chairman man lamang ng Kabataang Barangay! Paano ka naman makakagawa ng pagbabago sa bayan ang isang walang karanasan at walang alam sa pagpapalakad ng gobyerno,” Imee declaimed.

Numerous sources claimed that Imee was a leader of her father’s reelection campaign. As early as December 1985, according to Business Day, quoting “highly-placed sources,” Imee had reportedly been assigned to “take over the presidential and vice-presidential campaign in Metro Manila,” principally using a “reactivated” Kabataang Barangay as “foot soldiers.” According to an article published in Ang Pahayagang Malaya on January 22, 1986, quoting Ross Tipon, head of the opposition coalition Unido, “Member of Parliament Imee Marcos-Manotoc, recently held a dialog with Laoag City Mayor Rodolfo Fariñas and barangay captains to ‘counteract the growing threat to the Marcos candidacy in Ilocos Norte from the youth sector,’ which resulted in “threats of bodily harm against students and youth volunteers [of the opposition] carried out by well-known Laoag City thugs.”

Imee also made the headlines for purportedly being the target of an assassination attempt while she was out campaigning for her father, though accounts corroborating the incident were scant. A headline from a January 8, 1986 Agence France-Presse report stated it factually: “Man with Gun Arrested Near Marcos’ Campaigning Daughter.”

Nothing she did during the 1986 election helped prevent the end of the Marcos dictatorship.

After Edsa

After Ferdinand Sr.’s ouster in February 1986, Imee joined her family in Hawaii for a short time, until she, her then husband Tommy Manotoc, and their children fled from the United States, relocating to Morocco and reportedly spending some time in Portugal, to avoid legal trouble. She was the last of the (living) Marcoses (Ferdinand Sr. died in September 1989) to return to the Philippines in December 1991. According to the Manila Standard, immediately after her return, when “[asked] if she had any political plans in the future, Imee said categorically that she still hadn’t made up her mind.”

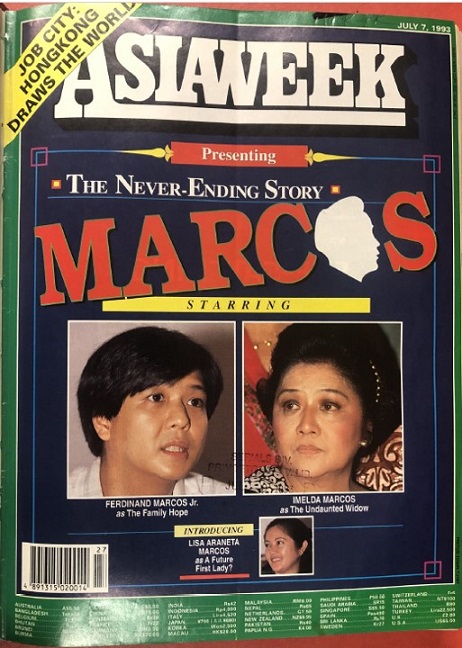

Between then and the publication of articles about her possible political comeback in the late 1990s, she was busy with the cases against her and family, spending a few years with her husband and their children as a “resident” in Singapore—through which she successfully prevented the enforcement of the US court decision to pay damages to the mother of Archimedes Trajano, found dead after questioning Imee’s leadership of the Kabataang Barangay—grieving for her father after his body was flown back to the Philippines in 1993, and splitting up with her husband; she ceased to be “Imee Marcos-Manotoc” when she campaigned to become the congressional representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte in 1998.

In October 1996—over a year after her mother was elected representative of the first district of Leyte and after Bongbong failed to win a seat in the Senate—Imee flew back to the Philippines from Singapore. In the same month, newspapers such as the Manila Standard bannered her political plans, which apparently stirred up the post-Edsa political order in Ilocos Norte. It was initially suggested that she would run for the first district seat, but she eventually went for the second, going head to head with her “grand uncle,” Simeon Marcos Valdez. She won handily, even if Valdez reportedly had the backing of his nephew, then outgoing President Fidel Ramos.

The outcome of the 1998 elections was overall agreeable to the Marcoses, to say the least. Though their matriarch Imelda gave up her second attempt to secure the presidency, the candidate they supported, Marcos loyalist Joseph Estrada, became chief executive. And besides Imee, Bongbong also became a local government official, winning back the governorship of Ilocos Norte. Both Imee and Bongbong would hold their positions for three consecutive terms (1998-2007), while their mother seemingly retired from politics.

Reluctant politician, dutiful child

Imelda seemed particularly emboldened by the turn of events. In December 1998, the Philippine Daily Inquirer serialized her infamous interview with Christine Herrera, where she claimed that her family “practically owned everything in the Philippines.” Peter Goodspeed of the Canadian newspaper National Post, noted Congresswoman Imee’s response to her mother’s claim: “‘We love her dearly,’ she said with a nervous laugh during a television interview, ‘but she is wild and crazy, and it’s very exciting to watch. But let’s see.’”

With her “wild and crazy” mother not exactly helping to draw sympathy for her family, why did perennially reluctant candidate Imee return to the political arena? In a June 1997 interview published in Lifestyle Asia, Imee said: “There seems to be this obligation to return to the family firm, but at the moment, I’m very much of two minds. I’m a very reluctant politician.” In November 1999, a little over a year after she won her congressional seat, Imee was interviewed by Marites Sioson for the San Francisco-based publication Filipinas. Point blank, she was asked, “Why did you run?” Her response: “It was largely a duty-based decision. They couldn’t come up with another candidate in Ilocos Norte, and when my brother was campaigning, I was asked to pitch in.” She claimed that she “more or less signed on as a six-year contract because you can’t achieve anything in three years,” suggesting that her reelection was guaranteed.

She did win a second term. During that term, in an interview for the magazine Flip, published in April 2003, Imee said, “I’m a very reluctant politician but also a dutiful child. Basically my brother bludgeoned me into it, and my deal with the family was, OK, two terms. Three terms is useless, one term is too short to do any good. But that’s it. I’m the type that reads a lousy book to the very end all because I started it. So now nandyan na ako so kailangan panindigan na.”

Such statements may have contributed to the belief that Imee would present herself as a candidate for higher office, specifically the Senate, in 2004. By then, Imee had been identified as a member of the opposition against an administration led by Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who, in January 2001, acceded to the presidency after the “constructive resignation” of Estrada following “Edsa Dos.” Being a member of the opposition, Imee spun one of the most significant court decisions ordering the return of her family’s ill-gotten wealth, the Renato Corona-penned Republic v. Sandiganbayan, promulgated in July 2003, as an instance of politicking.

Imee told the Philippine Daily Inquirer at that time that she was “‘seriously considering’ running for senator” in 2004, since she had been “‘going around the country, and [she was] very, very well received naman.” In October 2003, she told the Philippine Daily Inquirer that she and her brother “inherited a tremendous amount of baggage”—as if they were not themselves direct participants in the Marcos dictatorship—such that running as a Marcos was a handicap. “Well, all I have to say is give us a chance and maybe you will get to know us better,” she pleaded.

Apparently, more than one coalition was interested in including her in their 2004 senate slates, including Raul Roco’s Aksyon Demokratiko (supposedly they wanted her along with an Aquino scion, then representative Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III) and the Fernando Poe Jr.-led Koalisyon ng Nagkakaisang Pilipino. Though many thought that Imee was a shoe-in for the Senate, she ultimately decided to run for reelection in the Lower House instead.

As relayed in an Inquirer article dated January 9, 2004, Bongbong explained his sister’s decision thusly: “For a candidate to run for the Senate is one thing, and for a Marcos to run for the Senate is another thing….The possibility of being cheated is already a concern for [Koalisyon standard-bearer] FPJ; what more us?” Bongbong was speaking from perceived experience, given his unwavering belief that cheating had marred his 1996 attempt to become the first Marcos elected to national office after 1986.

Imee’s third term at the House ended in mid-2007. Throughout her stay in Congress, besides her appearances in magazines, one reader of the Inquirer noted that she had become a “talk show fixture.” Recalling her Kabataang Barangay days, she continued to portray herself as a staunch opponent of US military presence in the Philippines. In her last term, she was appointed a member of the powerful Commission on Appointments as the minority bloc representative. Though it was against her family’s interests, she did not “aggressively” block nor lobby against the first iteration of the bill to give reparations to human rights violations victims during the Marcos dictatorship, according to then Akbayan partylist representative Etta Rosales.

A betrayal, on Imelda’s orders?

In 2005, she was also one of the prominent signatories of an impeachment complaint, whose lead complainant was KBL stalwart Oliver Lozano, against President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. The complaint paved the way for photo opportunities among Imee and legislators of the left-wing Makabayan bloc, echoing an earlier magazine photoshoot that she had with “fellow opposition” members Teddy Boy Locsin and Satur Ocampo.

However, during the vote of the House regarding the complaint, Imee was a no-show, contributing to the junking of the articles of impeachment. In May 2006, Imee said that she was absent during the vote because her mother told her to be. Speculation was rife that the Marcoses were working out a deal with Macapagal-Arroyo to have Ferdinand Sr. buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani, but no such deal was reached.

Thus, by the time her stint in Congress ended, Imee seemed less famous for being a Marcos than being an outspoken legislator-cum-celebrity, who became somewhat palatable even to Marcos critics because of her stance against an unpopular president and her policies. She was again thought of as a senatoriable; in one pre-election poll, conducted by the Ibon Foundation in October 2006, Imee ranked third among a list of 60 possible candidates. Apparently, her “winnability” was insufficient to convince her to run at that time. In fact, she opted not to run for anything at all in 2007.

A break from politics, not from being a Marcos

The Filipino Express, a US-based periodical, published an article titled “Imee Quits Politics to Write about Father” on June 25, 2007, a little over a month after that year’s elections. She rebutted claims that she was stepping away from politics because her partner, Singaporean Mark Chua, told her to; apparently, her sister-in-law, Bongbong’s wife, Liza Araneta Marcos, was the source of the rumor. “In truth, he [Chua] wanted me to run,” Imee said. During a press conference in Ilocos Norte, she stated: “I’ve always been a reluctant politician, but I seem to be drawn back into politics time and again.” Because of her “reluctance”—or perhaps the family’s belief that they could flit in and out of politics in their northern fiefdom with ease, so secure is their control over the province—her brother decided to support the candidacy of their cousin, Michael Keon, for the governorship of Ilocos Norte, while Bongbong himself successfully replaced Imee in Congress. Freed up from playing politico, Imee claimed that she was going to fulfill an assignment given to her by her late father, to “write about his life and works during his two-decade administration.”

Imee’s writing project was still ongoing as of December 2008, according to Manuel Alba, Ferdinand Sr.’s former budget minister, in an interview with professors Teresa Encarnacion Tadem, Cayetano Paderanga, and Yutaka Katayama. But to this day, Imee has not released a book about her father that she wrote herself; thus far, the only book she has (co-)authored is PinakBEST! Recipes from the Marcos Kitchen and More (2022), published by IPROD, Inc., of which she was (is?) “officer-president.” Soon after her 2007 “retirement” from politics, however, seven books, published by the Marcos Presidential Center, which was headed by Imee, were launched on July 7, 2007, or 07-07-07—seven being Ferdinand Sr.’s lucky number. All these books—authored by eminent persons such as political scientist Remigio Agpalo and historian Samuel Tan—were meant to portray Ferdinand Sr.’s rule in a positive light. It seems likely that they were written and set for publication while Imee was still a member of the Lower House.

Besides helping to sanitize her father’s dictatorship, during her second political interregnum, Imee also tried to help reclaim her family’s wealth. A few weeks after the launch of the pro-Marcos books, Imee asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to halt the stock offering of GMA Network, claiming that the shares owned by the Duavits, one of the network’s major shareholders, were actually her father’s. Imee’s letter-complaint was disregarded by the SEC, and the initial public offer of GMA proceeded. In her complaint, Imee practically admitted that her father had numerous “dummies” who held stocks for him, somewhat supporting her mother’s claim that they “own everything,” as well as giving further evidence that Ferdinand Sr. circumvented constitutional limitations on his income when he was president.

Imee would also pursue other interests, specifically in film. A few days after her SEC filing, she launched the Creative Media and Film Society of the Philippines, or CreaM, a multi-media production outfit. She described herself as “citizen Imee,” “Kaya mas marami na akong magiging oras for this organization,” to Ruel Mendoza of the blog Commuter Express. In her capacity as head of CreaM, she became an annual fixture of the Philippine Youth Congress in Information Technology, which, at least in 2008 and 2009, brought her back to UP Diliman as a resource person. CreaM was not entirely apolitical, however; in August 2009, it co-produced the animated film Ligtas Likas for then Senator Loren Legarda, and around September that year, created a website for Bongbong Marcos, bongbongm.com, as well as campaign videos for his successful 2010 senate run.

Returning to politics for the family’s sake (again)

Imee herself—as always, so she says, reluctantly—ran for elected office once more in 2010, this time to be governor of Ilocos Norte, against her cousin Michael Keon. The reason was, again, a mix of filial obligation and political strategy: Bongbong was then a Nacionalista, having ditched KBL a year before, while Keon was a member of another party. Keon was not supporting Nacionalista’s standard bearer, Manny Villar. Later on, during the campaign season, Keon claimed that he was the “adopted candidate” of the Noynoy Aquino-led Liberal Party. Imee blamed Keon for her return; “Kasalanan niya ito e kasi kung gusto ko sana maging gobernador 2007 wala naman akong kalaban,” GMANews.TV quoted her as saying shortly before the 2010 elections. “It looked like Bongbong’s candidacy would be compromised and we couldn’t allow that. And it was also a direct challenge to my father’s legacy here in the province so that was also untenable,” she rationalized.

Recruited to run for Imee and Bongbong’s old House seat was their mother Imelda. All three of them won. Imee would remain governor of Ilocos Norte for three terms. Among her first acts was to launch a tourism campaign, “Paoay Kumakaway!” Closely involved in the campaign was her own production outfit, CreaM.

During her third and last term as governor, she was once more painted to be a senatoriable by pundits and PR people, considering that the Marcoses were at the time allied with the president, Rodrigo Duterte. In 2017, Imee claimed that her family had not yet discussed the possibility of her running for senator in 2019, as all of them were still focused on Bongbong’s electoral protest, which he launched after he lost the vice presidency to Leni Robredo. In early 2018, she was sending out feelers to the electorate, saying that she was considering a senate run because her brother decided not to attempt a return to the Senate in 2019, and claiming that the north (Ilocanos?) still need representation in the Upper Chamber.

According to GMA News, when she filed her COC for senator in October 2018, she said, “Most of the candidates are incumbent senators, so I figured there should be a representative for the local government who will push for helping the farmers and bringing down food prices.” Her brother, children, and mother accompanied her during the filing of her COC.

Thus, though supported by her family, unlike in previous election cycles, Imee did not portray herself as being pushed to run by a parent or her brother in 2019. Political scientist Maria Ela Atienza, however, noted that the family likely wanted to remain nationally relevant, as Bongbong becoming a senator “was not enough to leave a lasting impression.” Imee won—the third Senator Marcos after Ferdinand Sr. and Jr.—weathering accusations of misuse of tobacco excise tax proceeds while she was governor and clear evidence that she had been lying profusely about her academic credentials.

Perhaps having a Marcos in the Senate did help Bongbong win the presidency in 2022. Imee certainly did have a role in setting up what led to the Bongbong-Sara Duterte “Uniteam” tandem, besides supposedly providing crucial initial support that led to the Dutertes’ rise to the national political arena. In 2021, Imee claimed that it was Sara who convinced Bongbong to run for president. In 2023, Imee affirmed Sara’s claim that the former convinced the latter to run for vice president alongside her brother. Sara reiterated this in her October 18, 2024 press conference, adding that Imee purportedly told her that the tandem was necessary to beat Leni Robredo. From being pushed and pulled by family, Imee apparently tried her hand at playing political matchmaker and kingmaker during the 2022 elections and succeeded—to a certain extent.

A few days before Sara’s revelatory press conference, during the October 10 Pandesal Forum with Wilson Lee Flores, Imee said, “Hindi ko naman first choice ang pulitika pero napilitan at ‘yun ang utos ng mga kababayan ko sa Ilocos Norte. Napilitan akong tumakbo kahit na hindi ko naman kagustuhan. Pero ganyan talaga eh.” Forty years on after first claiming to be “napilitan,” Imee still claimed to be reluctantly heeding a call of duty, but more in response to vox populi than vox Imelda. Heaven forbid that her reasons for running were the preservation of her family’s political gains and a reasonable chance of winning.

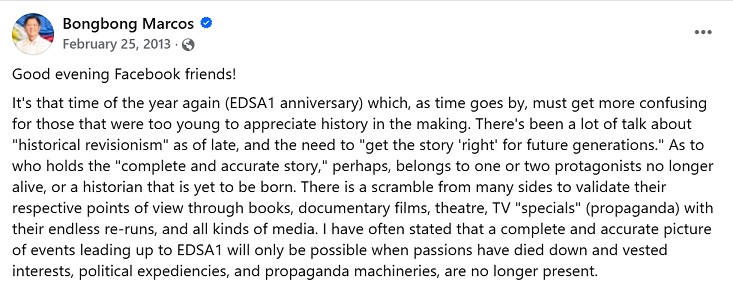

In the lead up to the 2025 elections, with her friend Sara beside her, Imee’s stated reasons for staying in the race seemed a lot more vague: she is, supposedly following her father’s footsteps, #IMEEnanindigan, who stood up for what is right, and she will fight for the downtrodden and those deprived of justice—part of the message is that she will fight for the oppressed Dutertes. In the final stretch of the campaign, she seemed to reconcile her allegiance to her (immediate) family with her partiality for the Dutertes by making a bold claim: “Ang gobyerno ngayon [under her brother] ay hindi Marcos. Ang gobyerno ngayon ay Romualdez [presumably referring to her cousin, House speaker Martin Romualdez] at Araneta [likely referring to Bongbong’s wife, Liza Araneta-Marcos].” Gatekeepers supposedly keep Bongbong from heeding, or even hearing, Imee’s sisterly counsel. Her brother and the Dutertes may be enemies at the moment, but that doesn’t mean she considers herself an enemy of her brother as well.

In fact, during a press conference held on April 29, Imee insisted that she has never quarreled with her brother; “yung mga amuyong sa Palasyo, mga nariyan, mga lulong, ayun, sila, sila po ang ating kaaway.” In an earlier press conference, held on March 27, she said that she was always her brother’s manang (elder sister), and “mula pa noong bata kami parati naman siyang pinagbibilin ng tatay ko na alalayan, ang problema hindi ko na magampanan at maraming humaharang, hindi nakikinig, hindi ko alam.”

And what sort of advice did she dispense? In 1982, during an interview with Marra PL. Lanot, Imee had this to say about her brother, then vice governor of Ilocos Norte and special assistant to the president: “My brother is much more relaxed, and he enjoys life. He has no scruples perhaps, a little less conscious about having a good time. I’m always worried that this is not quite the best thing to do.”

Could it be that in Imee’s eyes, steering her brother in the right direction is a fulfillment of her filial duties, and she is best positioned to do so as a senator? If her “opposition” to her brother is simply an expression of sisterly concern, beyond the recently concluded elections, what will Imee do if helping the Dutertes greatly harms her brother, or her family’s reputation, which she has labored for decades to rehabilitate?