Originally published by Vera Files on November 11, 2024

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. was spinning a tale when he talked about his father’s Bicol River Basin Development Project during a situation briefing on Oct. 26 in Naga City on the massive floods unleashed by severe tropical storm Kristine.

“Itong mga lugar, mga Batangas, mga Cavite, nawala kaagad ang tubig. Dito, hindi nawawala ang tubig. But that’s the proverbial problem of the Bicol River Basin,” he said. “So, we have to find the long-term solution.” (In Batangas, Cavite, the water was gone quickly. But here, the flood has remained)

Marcos said he is studying the problem and found that in 1973, during his father’s presidency, there was the Bicol River Basin Development Project (BRBDP) funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Asian Development Bank, and Japan’s then Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency, with the European Union included in the planning.

He said he read a study by someone from the University of the Philippines which found that despite some challenges, the project helped a lot. “Iyon lamang hindi natapos. In 1986, when the government changed, nawala na iyong project, so basta’t natigil. So, we have to revisit it now,” he added. (But it was not completed. In 1986, when the government changed, the project disappeared, it just stopped.)

Bongbong repeated his line concerning the BRBDP’s demise in a media interview after the briefing, saying the project helped in flood control, but that it was abandoned after the change in government in 1986.

In response to Bongbong waxing nostalgic about the BRBDP during his father’s time, Manuel Bonoan, secretary of the Department of Public Works and Highways, noted during the briefing that the Philippine-Korean Project Facilitation project -the Bicol River Basin Flood Control Project- was updated only this July 2024 including the feasibility study for the flood control program. “So, by early next year, we will be doing the detailed engineering design,” he said.

Bonoan’s response may have been intended to assure the president that there were still big-ticket Bicol River Basin projects today, just like the time of Marcos’ father. Still, it did not exactly refute Bongbong’s claim that the BRBDP was abruptly stopped after the 1986 People Power Revolution. Nobody during the briefing challenged the president’s assertion.

Flowing with the President’s fiction

So far, neither has any mainstream news outlet. The Philippine Daily Inquirer published an article titled “Marcos Draws Focus to Bicol River, Recalls Father’s Halted Project,” on October 27. It noted the exchange between Marcos and Bonoan but did not counter the claim that the program was discontinued after Marcos Sr. was deposed. Philstar.com uncritically quoted Bongbong’s claims regarding the BRBDP verbatim. An article published in GMA News Online went a step further: it fully supported Marcos’s claim, citing an interview with Bonoan. According to the article, “Launched in the 1970s under the administration of late President Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the BRBDP was a geography-based development initiative for the Bicol Region. However, it was halted in 1986 when the Corazon Aquino administration took over.”

The closest to a counterclaim by someone from the media came from investigative journalist Raissa Robles, who tweeted, “Kung natigil man ang BRBDP, hindi dajil sa Cory govt, which is what MJr is implying. Blame the Villafuertes who have been in power there.” (Had the BRBDP been stopped, it was not because of the Cory government)

Decentralization and reorganization

Factually, Cory Aquino’s Executive Order no. 374 on Oct. 30, 1989 shut down the BRBDP Office along with integrated area development (IAD) offices in Bohol, Cagayan, and Mindoro. But not simply because it was a Marcos project; Aquino’s order stated that the closure of these offices was due to the reorganization of regional development councils (RDCs) and the strengthening of local governments in line with the 1987 Constitution. “[S]pecific elements of decentralization now render feasible the shift in the institutional arrangements for the IADs, where the RDCs and LGUs concerned may now assume active responsibility and authority over the same,” said one of the order’s “whereas” clauses.

The order creating the BRBDP, Executive Order no. 412, dated May 7, 1973, established a national-level Bicol River Basin Council that was under NEDA; Presidential Decree no. 926, dated April 28, 1976, turned over the program to an office under the Cabinet Coordinating Committee on Integrated Rural Development Projects, still under NEDA. Cory’s order turned over the tasks of that national office to the RDC of the Bicol Region and the governors of Camarines Sur and Albay.

In fact, Aquino’s order hewed closely to a principle stated in Marcos Sr.’s presidential decree: “the success of the program requires that the management and planning of the basin area be comprehensive, decentralized, and framed within regional and national plans.”

Decentralization was a governance buzzword at the time the decree was issued. In a book chapter they wrote, scholars G. Shabbir Cheema and Dennis Rondinelli noted that in the 1970s and the 1980s, “globalization forced some governments to recognize the limitations and constraints of central economic planning and management.” This led to what Cheema and Rondinelli called the “first wave of post-World War II thinking on decentralization,” which “focused on deconcentrating hierarchical government structures and bureaucracies.” The Marcos Sr. administration apparently tried to latch onto this trend—in the same way that it tried to adopt other buzzwords such as “human settlements”—but, being a dictatorship, did not fully commit to decentralizing power.

A May 1985 USAID paper, “Integrated Rural Development Projects: A Summary of the Impact Evaluations,” written by Cynthia Clapp-Wincek, explained the BRBDP command structure: “Individual ministries took the lead in implementing activities in their scope of responsibility but coordinated with other ministries where appropriate. There was an advisory committee for private sector involvement, a coordinating committee for provincial governors and regional directors of line agencies. At the local level, there were Area Development Teams with mayors, representatives of the line agency staffs, city legislative councils and BRBDP staff.”

This complex top-down structure resulted in what Clapp-Wincek referred to as impeded momentum: “High political commitment got [the program] moving early on—but momentum was slowed by the elaborate institutional arrangements.” Lost in this bureaucratic quagmire was the voice of the program’s supposed beneficiaries. Clapp-Wincek said that “mayors did not seem to have an intimate understanding of their constituents’ concerns. . . . [there was] little correlation between the ‘issues raised in the minutes of Area Development Team meetings with the issues raised by farmers in their conversations [with USAID’s Bicol IAD evaluation team].’”

Victoria Bautista, in a 1986 Philippine Journal of Public Administration article titled “People Power as a Form of Citizen Participation,” mentioned a 1981 survey that found “only 41 per cent of the respondents [e.g., farmer beneficiaries] acknowledged having participated in deciding the main components included” in the BRBDP; “most physical infrastructure projects chosen for inclusion in the feasibility analysis were taken from inventories of capital projects submitted by the local government for national funding.”

Such were the administrative assessments of the BRBDP Office before it was dissolved. During the Naga City briefing, Bongbong did not specify whose BRBDP study he cited (while speaking about the study, he was holding a few stapled sheets that were separated from a pile of documents by Anton Lagdameo, Special Assistant to the President). If he was referring to Jeanne Frances Illo’s “Models of Area-Based Convergence: Lessons from the Bicol River Basin Development Program (BRBDP) and Other Programs,” published between 2012-13, it’s indeed a paper that has some—not entirely—positive things to say about the program.

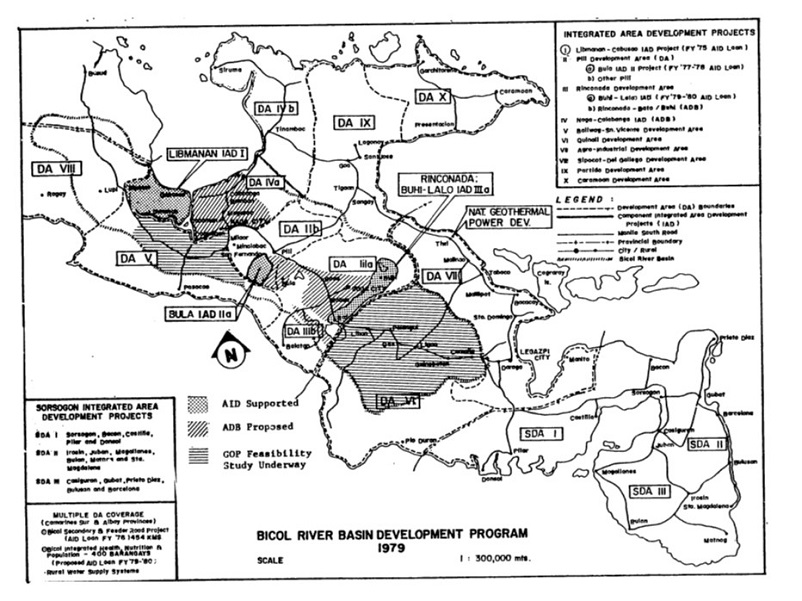

Illo noted that the BRBDP was “an early experiment in geography based planning, one that was independent of political administrative boundaries [as planning] and programming were focused in a ‘river basin,’ or a hydrologic area.” Illo affirms that the BRBDP was funded by foreign agencies—tens of millions from USAID and European Economic Community grants and ADB loans. A 1982 article published in Horizons, a USAID publication, said that by that time, the aid agency had “made two grants and five loans totaling $30.4 million to the Philippine government which, itself, has invested about $75 million.” Bruce Koppel, in a 1987 article titled “Does Integrated Area Development Work? Insights from the Bicol River Basin Development Program,” noted that “The total direct costs of the Program approximate $100 million, but the complete costs are certainly higher.”

Loans dry up, costs balloon but still no flood control

Illo wrote that the “USAID funding for the BRBDP ran for a decade (1973-1983), but the Program itself, or at least some of its components, went on for at least another decade.” Providing another context for Cory Aquino’s closure order, Illo continued: “When the grants and loans dried up, the Program Office was closed”; “[completed] infrastructure projects, however, were maintained and, later, rehabilitated or repaired by technical agencies [the National Irrigation Authority or NIA and DPWH] while the agrarian reform projects were subsumed under the succeeding Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program.” So, “basta’t natigil” is patently false.

If Bongbong insists that he is right, perhaps he can continue his studies, reading in particular a report on the Formulation of Integrated River Basin Management and Development Master Plan for Apayao-Abulug River Basin, produced by Woodfields Consultants, Inc. for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources in October 2014. The report’s executive summary states,

“From 1973-87, the [Bicol River] basin had been the subject of initiatives for management and development [BRBDP]. Then, from 1989-94, a Bicol River Basin Flood Control and Irrigation Development Program was implemented. A grant from the World Bank (WB) to undertake a master plan was conducted in 2002-03 which led to the creation of a Project Management Office (PMO). The PMO did not survive after the WB support had ceased. The national government, through the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA), had re-activated and has repackaged the program and in 2007, the approved program has received national government funding for DPWH and DENR projects. The proposed river basin management council has not seen fruition.”

Funding is a perennial challenge. Writing in 2004 about the Macapagal-Arroyo era efforts, specifically the World Bank-funded Bicol River Basin Watershed Management Project, Juan Escandor of the Philippine Daily Inquirer noted that the Marcos Sr.-era BRBDP “failed to achieve its major output: a huge reservoir in the middle of the Bicol river basin area”; “The national government was forced to abandon the project in 1989 because of the ballooning costs of the infrastructure component estimated in 1992 at $274 million,” Escandor added.

Not that that “major output” was anywhere close to completion before 1986; a 1977 JICA report on the establishment of flood forecasting systems in the Agno, Bicol, and Cagayan River Basins, noted that at that time, “[the] only project under construction is ‘Cut-off No. 3’ which is intended to alter meandering in the vicinity of Naga City.” The “future programs” JICA mentioned, such as “drastic projects such as the dyke system in the lower course, direct drainage from Lake Bato to Ragay Gulf through diversion channels dams in the upper Sipocot river,” were pipe dreams. And they remained so come 1979: the “Bicol Biennial Evaluation” of the Government of the Philippines and BRBDP-USAID, released in August of that year, noted that “projects packaged and funded so far are capital construction infrastructure development, principally roads and irrigation with some institutional development”—not flood control. Concerning the existing efforts, USAID noted that “the overall picture of the Bicol Program test case in Integrated Area Development is mixed.”

Poor engineering design, other project woes

Moreover, Illo notes that “[poor] engineering design had reportedly plagued the Libmanan IAD Project,” a major USAID-funded BRBDP project that “involved the construction of a 4,000 hectare irrigation and drainage system plus flood control, salt water intrusion protection facilities, and farm access roads in an economically depressed area in the lower Basin that was considered to have high growth potentials.” Other issues that hampered that particular project include “inadequate coordination between the NIA and the BRBDP, environmental damage, and poor institutional development.” Thus, Illo said that “by the end of USAID funding in the mid-1980s, the constructed system was serving only half of the irrigable area.”

Illo also noted that for another BRBDP initiative, the Bicol IAD II project, “NIA installed an electric pump irrigation system in the area, neglecting to consider the cost of electric power that has been consistently much higher than in Metro Manila. The [farmer’s] cooperative ran huge electric bills, and decided to return the pumps to NIA and buy its own crude-oil-powered pumps.” Clearly, the BRBDP was hardly a flat-out success even before “the government changed” in February 1986.

Other sources affirm this. Koppel, in his 1987 article, and Doracie B. Zoleta, in another 1987 article titled “From the Mountains to the Lakebed: Resource Problems and Prospects in Buhi Watershed, Camarines Sur, Philippines,” noted a concerning incident in a project involving the BRBDP called the Buhi-Lalo Upland Development Pilot Project. It initially started well, with farmers undergoing University of the Philippines-led training and participating in local reforestation efforts. However, due to the mishandling of funds, payments to rural workers involved in building the project’s training facilities were delayed by eighteen months. The wage-deprived workers engaged in arson, culminating in the burning down of one of the major facilities in April 1985.

Zoleta’s article, and another source, “Lessons from EIA for Bicol River Development in Philippines,” written by Ramon Abracosa and Leonard Ortolano, also took note of the adverse environmental effects of the BRBDP Lake Buhi water control structure project. Citing a 1983 USAID Report, Abracosa and Ortolano stated that the project resulted in “increasing the frequency of sulphur upwelling and the continuing denudation of the lake’s watershed.” Zoleta noted that this “killed fish, especially those trapped in fish corrals and cages.”

Investigative journalists have also noted how the USAID grants for the BRBDP can in certain instances be considered a form of “tied aid.” According to a 1991 article titled “US Grants: How Free are They?” by Marie Avenir, Lucia Palpal-Iatoc, and Ma. Lourdes M. Reyes of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, USAID provided a grant/soft loan in 1979 to the BRBDP to train “400 barangay health aides in Camarines Sur and Albay to help improve health and nutrition among residents, maintain population growth at a desirable level, and achieve local governments’ self-reliance in health services.” But the financial assistance was not driven entirely by altruistic motives. The journalists noted that the project “virtually became a market for US goods through stipulations that vehicles be bought from the US and drugs and health kits procured for the program be subject to approval of USAID.”

C.P. Filio, in an article published in Manila Standard on Sept. 7,1987, wrote that the BRBDP caught the interest of Americans “because of their desire to showcase their highly successful experience in the Tennessee Valley Authority” in the 1930s. Filio noted the USAID’s 1983 assessment of the program’s agricultural contributions was favorable (and self-serving), but the farmer beneficiaries thought otherwise; Filio claimed that 1985 regional indicators showed that poverty incidence—“73.2 percent of families living below the poverty line”—was highest in the Bicol region, “no thanks to the Bicol River Basin Development Program.”

According to a declassified US State Department cable from 1982, titled “Ambassador’s Visit to the Bicol Region, November 15-16,” officials of the Philippine government—including the BRBDP director and the governors of Albay and Camarines Sur—“were especially receptive to [US Ambassador Michael Armacost’s] proposal that the scope for possible U.S. agribusiness investment in the Bicol provinces be explored.” But this possible penetration of the Philippine agricultural market was seen to be hampered by the “peace and order situation” in Bicol, i.e., the communist insurgency. Another cable, dated Sept. 17, 1982, implied that the insurgency was less present in the “lowland area between Naga and Legaspi” that was covered by the BRBDP, but the “Quezon-Bicol Triangle” between Lucena City and Naga, including the entirety of Camarines Norte, was a hotbed of insurgency and criminality. In short, the US’ focus on the “Bicol River Basin experiment” contributed to uneven development in the region, possibly exacerbating the insurgency in underserved areas right beside the priority areas.

BRBDP did not fold up simply because Marcos Sr. was deposed

Again, even if there were numerous reasons to discontinue the BRBDP after the program’s main sources of funding dried up, or at least to reevaluate it, it definitely did not fold up simply because Marcos Sr. was deposed. In fact, the continuation of the BRBDP after the EDSA revolt was crucial to the political career of Jesse Robredo, husband of former Vice President Leni Robredo, twice a political rival of Bongbong.

According to Takeshi Kawanaka, in his article “The Robredo Style: Philippine Local Politics in Transition,” Jesse Robredo was appointed as Program Director of the BRBDP after the EDSA Revolution. Kawanaka noted how being in the BRBDP helped Robredo gain political capital, with the development planning of Naga City as his last project as director. Robredo rose to become Naga City mayor in 1988.

PIA plagiarizes Jeanne Frances I. Illo

Again, did Bongbong really have to lie about the BRBDP? It is interesting to note that on the same day as the Naga City briefing, the Philippine Information Agency published an article titled “PBBM’s Bicol Visit Injects Fresh Ideas into Old Dev’t Project.” Without citing any sources, it described the BRBDP as a “$46.8-million [foreign-funded] package” that was criticized because of “its heavy focus on physical infrastructure,” but resulted in “notable development of rural organizations and institutions.” Benefits were supposedly noticed during the “mid-1980s,” specifically because of BRBDP road projects, “as manifested in greater mobility, travel time savings, improved access to markets as well as to medical, educational, and recreational facilities, and trade.” The article noted that despite these long-term benefits, “certain problems linked to the program and the natural geography of the river basin still persist.” It then listed three IAD projects in Camarines Sur—without detailing their current status—closing with a call for better project design, transparency, and people’s participation in decentralization. PIA asserted that BRBDP needs to discard its “centralized, top-down approach, which limits local input and ownership, affecting sustainability.”

All of these are traceable to Illo’s article. The “greater mobility, travel time” line is lifted almost word-for-word from Illo. PIA’s article plagiarizes Illo’s work, down to the recommendations. As can be gleaned from the title of the article, PIA even lies about when these recommendations came about. “The discussion on the BRBDP has drawn out some reflections, ideas, and recommendations from Cabinet Secretaries present during the Camarines Sur briefing,” the government information agency stated. Absolutely not—these were Illo’s “reflections, ideas, and recommendations,” written over a decade ago, citing sources as far back as the 1970s.

Thus, while the PIA article does not reiterate the claim that the BRBDP ended in 1986, it still supports it, first by copying the claims of a credible source without attribution, making sure to exclude content from that source that refutes the president; then by making it appear that Marcos Jr.’s statements were the only reason for stirring up the program’s “revival.”

Since Bongbong took office, government propagandists have a track record of amplifying his and his family’s line that all went downhill after 1986, so it is necessary for a Marcos to course-correct the country. For instance, they publish articles claiming that Marcos Sr. pushed for genuine land reform, and that Bongbong will fulfill that dream; or that Marcos Sr. himself conceptualized a subway for Metro Manila in the early 1970s, and that Bongbong is now, finally, turning that plan into a reality. It is as if the time between 1986 and 2022 was a dark age, best forgotten, when absolutely no developments related to these programs and projects happened—contrary to fact.

Distorting history, cherry-picking and plagiarizing sources to support a false claim—why do they have to lie? This is how Marcos myths are formed and sustained. Falsities are, with a straight face, presented as facts, affirming the Marcosian Grand Narrative—all was well, golden even, until the Edsa “power grab.” A government propaganda agency supports the claim, while mainstream media uncritically reiterates it.

The lie can be uttered in various settings, such as political rallies or post-disaster briefings. Perhaps the lies are even particularly effective during tragic situations: should we not rejoice, actual competency and commitment to fact-based decision-making aside, that a Marcos is in Malacañang during trying times?