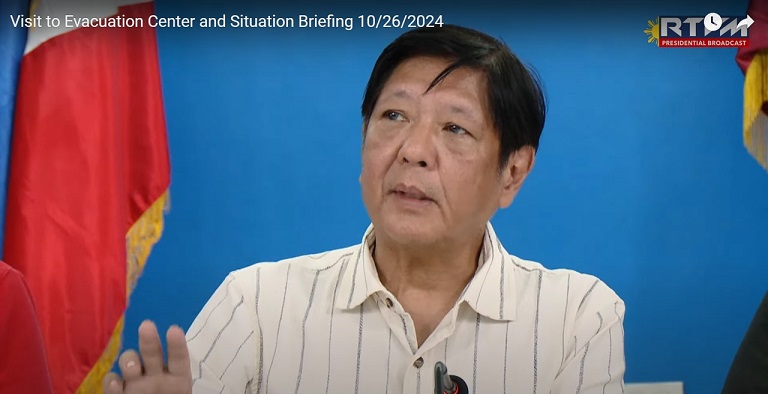

Unlike Sara Duterte, Carlito Dimailig issued no threats and just did it.

Imelda hacked

Fifty-two years ago this month, with martial law eleven weeks in effect, at around five in the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1972, Carlito Dimailig lunged at then First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos with a 12-inch bolo.

Conspicuous in a dark suit, Carlito went up the stage where Imelda was awarding the winners of the 1971-72 contest of the National Beautification and Cleanliness Council at the Nayong Pilipino in Pasay City. Carlito went with the South Cotabato delegation that won the first prize as a model province. He was the last in line. When he was just about three feet from Imelda, Carlito pulled the bolo from his left sleeve and stabbed her.

Imelda parried Carlito’s attack until she fell on the stage. Carlito kept on hacking at Imelda as other people on the stage tried to subdue him while others were shielding Imelda and they tried to pick her up from where she fell and get her off the stage.

In that melee, Technical Sergeant Clemente Tadena of the Philippine Army shot Carlito first. He shot him in the cheek. The shot did not stop Carlito. Technical Sergeant Julio Jaymalin of the Philippine Marines tried to kick and tackle him. Jaymalin missed and landed on his back near Carlito. As Carlito was hacking at people surrounding him, Jaymalin shot him twice in the body. Carlito, 5 feet in height and of slight build, weakened by his wounds, was finally wrestled to the ground, facing down even as he was still holding his bolo. Several men pinned Carlito on the stage floor as he still struggled to let loose. Petty Officer 2 Bagnos Magno of the Philippine Navy drew his firearm, leaned on Carlito, and shot him in the head. In about twenty seconds, the assassination attempt was over. Carlito was dead.

It terrified the audience at Nayong Filipino and it was all caught on live television via the Kanlaon Broadcasting System, Channel 9. It was replayed so often in the succeeding hours.

It was also through television that Marcos, then playing golf at the Malacañang grounds, learned of the attack on his wife. “Fortuna [Marcos’s sister] and her children came running out of the Pangarap crying out in sobs that ‘Imelda has been stabbed in Nayon Pilipino’,” Marcos wrote in his diary on that fateful day.

A helicopter rushed Imelda to the Makati Medical Center.

As Marcos hurried to the hospital, he ordered that Nayong Filipino be put on lock down “and to apprehend all the participants (in the attack).” Imelda was already at the operating room when Marcos reached her after a ten-minute drive from Malacañang.

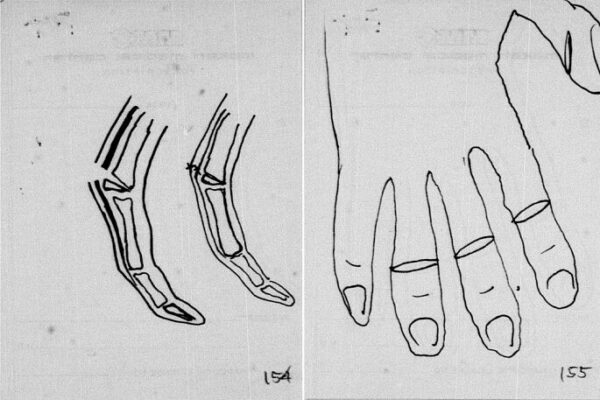

“She was on the operating table with ugly lacerations in both arms still oozing blood and her right hand cut on the second joint of the fingers so deep that I could see the bone and the cartilage of the middle finger severed. The tendon of the right forearm was obviously cut. It was a white protrusion in the bloody muscles that were being cleaned.”

Associated Press reported that “a team of surgeons took more than three hours to repair deep wounds in both hands and a one-and-one-half inch cut in her right arm which severed tendons. She also suffered several broken fingers shen she fell to the stage.” She had 50 to 75 stitches.

Shortly before 7:00 in the evening, Information Secretary Francisco “Kit” Tatad, in a press conference, announced that Imelda was out of danger according to her doctors. Tatad was with Dr. Constantino Manahan, the director of the Makati Medical Center. Dr. Manahan said that though Imelda lost a lot of blood, she was not in shock. Her wounds in her arms and hands were not serious but she would have to remain in the hospital.

Tatad also mentioned that two other people were wounded in the attack. Jose Aspiras, then congressman and eventually Marcos’s tourism minister, was hacked in the head, and Linda Amor Robles, secretary of the National Beautification and Cleanliness Council, was stabbed in the left side of her back, near her rib cage. Both were attended to by the doctors at the Makati Medical Center. They survived their injuries.

On Dec. 9, 1972, Dr. Robert A. Chase of Stanford University School of Medicine came to check on Imelda. When US President Richard Nixon called on Marcos and offered his commiseration right after the attack, he also told Marcos that he will be sending over Dr. Chase. He gave Imelda a neurology exam to see if her arms and hands were working after the surgery. Imelda passed the test. Dr. Chase admired the work done by Imelda’s physicians. He left the same day he arrived.

Imelda was released from hospital on the night of Dec. 10, 1972. She returned to Malacañang to recuperate.

Who Was Carlito Dimailig?

They never seem to get his name right—or simply did not bother to. Press reports right after the attack, once his name was released to the media, identified him as Carlito Dimaali, Carlito Dimmali, and Carlito Dimahilig. In Katherine Ellison’s Imelda: Steel Butterfly of the Philippines (1988), he was not even identified. Beatriz Romualdez Francia, in Imelda: A Story of the Philippines (1988), merely copied the name given to him by Remedios F. Ramos, E. Arsenio Manuel, Florentino H. Hornedo, and Norma G. Tiangco in Si Malakas at si Maganda (1980): Carlito Limailig.

James Hamilton-Paterson in America’s Boy (1998) is another example of these authors who do not let a name get in the way of their story. “His name was later given variously as Carlito Dimaali or Limaili, believed to be either a Moslem from the south with a grievance or a resident of Batangas with no personal motivation.”

But Marcos knew exactly who Carlito Dimailig was in less than 24 hours after his attempt on Imelda’s life.

When Marcos wrote in his diary about the assassination attempt on Imelda, he made a marginal note on the upper-left hand corner of his diary that he was writing the Dec. 7, 1972, entry “at 5:30 PM Dec. 8, 1972 at the Makati Medical Center, Room 904 where Imelda stays and where I slept.”

“While the assailant—a Carlitos [sic] Dimailig geodetic engineer of Calaca, Batangas, working in Davao may have been alone in the attack I believe he was only an instrument of vengeance or assassination.”

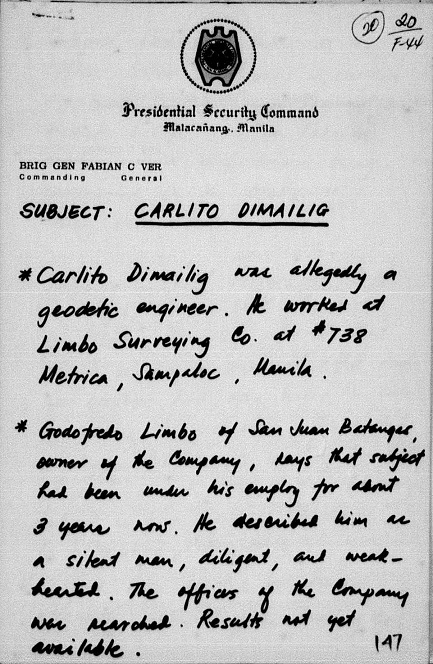

Marcos’s knowledge of Carlito could have come from Brig. Gen. Fabian C. Ver, the commanding general of the Presidential Security Command.

Among the digitized files of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) are Ver’s notes on Carlito written on the Presidential Security Command’s notepad.

Carlito’s sister, Dr. Thelma Dimailig, was a psychiatrist at the Veteran’s Memorial Hospital. She saw on television what Carlito did. Ver reported that she “rushed to Nayon Pilipino to identify the body” since “her brother had been under her care.” The Dimailigs were from Brgy. Puting Bato, Calaca, Batangas.

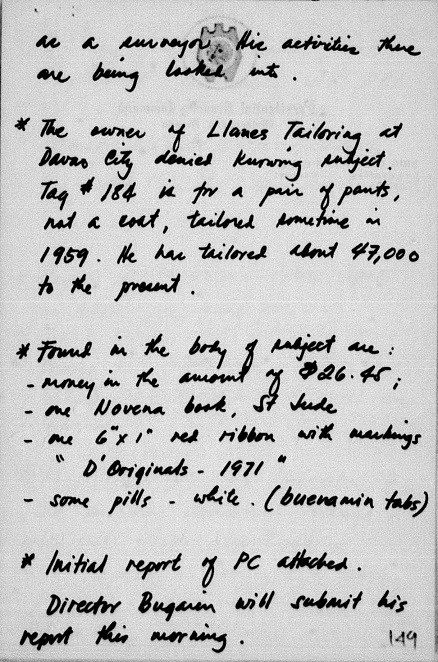

From Nayong Pilipino, Carlito’s body was brought to the NBI morgue. Found on him, according to Ver’s notes, were PHP 26.45, a St. Jude novena book, a 6 by 1 inches red ribbon bearing the marking “D’Originals-1971,” and some white pills (that Ver identified as “buenamin”).

In the PCGG files, next to Ver’s notes are two sheets of paper. The first one is a stationery marked “Office of the President of the Philippines.” It has these jottings: 1965 Mandaluyong—,

Hosp patient—, Geodetic Eng—, Godofredo Limbo—, Metrica, Sampaloc—. The second one is a torn slip of paper with the following notes: [possibly a four-digit number, a year, and a first name now unreadable for this was where the paper was torn] Dimailig, Carlito Dimahilig [the “h” scratched out], Calaca, Batangas—, Sister – a doctor working in Vet Memorial Hosp, schizophrenic. Written at the lower portion of the slip were possibly telephone numbers. These were scratched out. Both are in Marcos’s handwriting.

With Ver’s and Marcos’s notes are other reports on Carlito’s profile.

A licensed geodetic engineer

Carlito was indeed a licensed geodetic engineer. A graduate of the Manuel Luis Quezon School of Engineering.

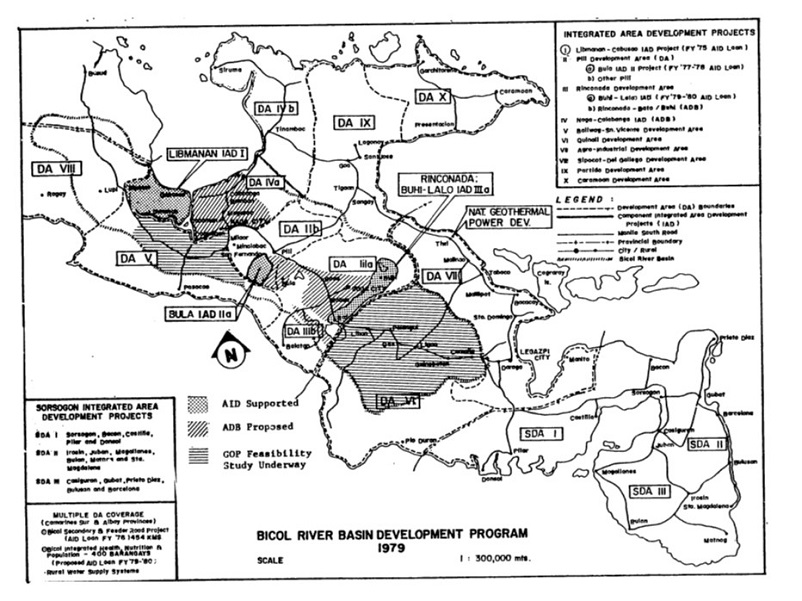

On March 21, 1969, he was hired as head surveyor at the Masara Project of Samar Mining Co. On September 1, 1969, a work supervisor reported Carlito to the main office of Elizalde & Co., Inc. as he was “acting very queer and it seems that he is mentally and emotionally disturbed” suggesting that “he be recalled to take a rest for about a month.” The supervisor feared that “he might hurt himself or others.” The following day, the supervisor noted in his report that Carlito had “returned to normal senses” and with a colleague was going back to Manila. Another supervisor attributed his “disturbance” to his “excessive drinking.” While in Manila by the end of September 1969, he promised “not to drink anymore . . . on his word of honor” and wanted to go back to work. Elizalde’s company refused. From then until that tragic day on Dec. 7, 1972, he was employed at Limbo Surveying at Metrica, Sampaloc, Manila.

Ver noted that Godofredo Limbo, his immediate employer, described Carlito as “a silent man, diligent, and weak-hearted.”

On Dec. 9, 1972, the Marcos-controlled press reported that authorities identified the assailant, but his identity was not to be mentioned in news reports yet. The foreign press was not as keen to follow this restriction. The next day’s Sunday Express almost bragged about a scoop as if it mattered in the censored press. “The Express learned from unimpeachable sources in the military the identity of the slain assailant and his other personal circumstances just a few hours after the attempt on the life of the First Lady was made.”

But just like the journalists and historians who wrote about the attempt on Imelda’s life, Marcos and his men proceeded to craft a more devious tale that made Carlito Dimailig’s identity irrelevant on who the Marcoses must punish and why.

Turning a threat into a tortured tale of conspiracies

Malacañang’s initial statement right after the attack on Imelda was matter-of-factly. In twelve sparse sentences it reported what happened, that “the president was shocked beyond words at the news.” It did not speculate on anything since “an investigation is in progress. The identity and motive of the assailant will be made known after the proper investigation has been made.”

In the morning of Dec. 8, 1972, after a thanksgiving mass at the Makati Medical Center, Marcos gave a few remarks to the press. He said he wished that he was with Imelda when the attack happened. That he should have been able to defend her.

“All I can say is that we are more determined than ever to remove all causes of criminality and disorder in our society.”

“I am all the more resolved, she and I, to proceed with the program to eradicate and eliminate all the threats against the stability of our society and to push through the reformation program.”

“When we undertook this experiment, we knew we would pay a price but I cannot forgive myself that it had to be her to pay such a price.”

But a few hours later, Marcos would be writing in his diary that the attempted assassination on Imelda was, in fact, all about him.

“Carlito Dimaila [Dimailig] of Calaca, Batangas, the assassin, was reported to have asked his sister, ‘How is it to kill the President.’ So he must have been after me.”

Kit Tatad, his public information secretary, mirrored Marcos’s mental calisthenics.

In his press briefing on the night of Dec. 7, 1972, notwithstanding Malacañang’s official statement, Tatad started peddling the story that the assassin’s real target was Marcos and not Imelda.

“Tatad said telephone callers had asked the Presidential Palace if Marcos was to be at the ceremony, perhaps indicating that he might have been the intended target,” the United Press International wrote in its Dec. 8, 1972 dispatch. The Times Journal of the same date continued Tatad’s tale on why anonymous persons were calling Malacañang and were keen to know the Marcos’s itinerary for the day. Because “up to the hour of departure for the Nayong Pilipino yesterday, it was not known to Malacañang aides whether the President would attend the affair.”

In an interview given an hour later to that of Tatad, Lorenzo J. Cruz, assistant secretary of public information, rung again the telephone tale. “It can be said now that since 3:30 this afternoon the study room of Malacanang has been receiving inquiries as to whether the president was going to Nayong Pilipino, although it was clearly announced that only the First Lady was going there in connection with the award ceremony for the beautification project.” It must be mentioned also that a printed program and a brochure for the awarding ceremony were made bearing only Imelda’s name.

With the media sicced on its way, it was only a matter of time before they dug up stories that suspiciously resembled what Marcos wrote in his diary.

From the Reuter-United Press International, Dec. 8, 1972: “Government investigators said the assailant apparently attacked Mrs. Marcos as a substitute for the president. Authorities identified him as Carlito Dimaali and said he lived about 60 miles from Manila. Capt. Ricardo Villanueva, heading the investigation into the attack, said Dimaali’s two sisters and a man tentatively identified as a brother were arrested and being questioned. Dimaali made statements to his sisters before the attack, investigators said, which indicated that he wanted to kill President Marcos. Investigators said Dimaali apparently thought Marcos was going to hand out prizes at an outdoor ceremony near Manila. His wife went to the ceremony instead.”

In the martial law-era crony press, there was no mention of Marcos enjoying a game of golf in the palace grounds while his wife was getting stabbed. What it reported was more of what Tatad told them to. Bulletin Today, Dec. 8, 1972: “What appeared very clear, according to Tatad, was that the assailant was able to go up the stage. He said that for the assassin to reach close to the First Lady required ‘some sort of cover.’ This would indicate, according to Tatad, that the assailant was not alone.”

The facile conclusion was: if the assassin was not alone, then it’s a conspiracy. Or even better: conspiracies.

In the same Dec. 7, 1972 evening press briefing, the Agence France-Presse reported that the government, through Tatad, “blamed a rightist conspiracy” for the failed assassination attempt. He “told newsmen this was borne out by confessions made by persons under martial law detention.” According to Tatad, these persons were “previously linked to an alleged plot to kill Mr Marcos ultimately leading to a rightist coup d’etat . . . the inclusion of Mrs Marcos as an object of assassination was not previously divulged . . . in order not to duly alarm the people.” The supposed confessions notwithstanding, “the plot continues, it is still active, and elements connected with this plot are still in Manila, Mr Tatad added.”

The next day, Dec. 8, 1972, Tatad delivered a speech at the opening of the conference on “Business Prospects” at the Plaza Restaurant in Makati. Here he laid out what the story must be. This mainly fed into the reports of the international press.

An assassin’s attempt on the life of Mrs. Marcos, the First Lady, put our nation on notice that we have not entirely subdued the political passion, the bitterness, and the violence that have long sought to claim the life of our President, in the hands of his enemies.

“The undertaking we began on September 21 will continue to mobilize the enemies. They will persist in the belief that their goals can be achieved by putting an end to the lives of our leaders. They will persist in the belief that their control of government can only be founded on the death of the President.”

“So until the conspiracy against the leadership—the conspiracy that began in December 1969—is fully liquidated, it can only be expected to continue. For we can dispossess all men of their weapons, but we can never completely purge all men of their hate. Seven times the

conspirators made an attempt on the life of President Marcos from early 1970 to this date; the plot not having succeeded and not having been fully terminated, continues.”

“Why then this attack on the First Lady at this time? . . . They perhaps believed that having been hurt where the essence of a man’s life lies, he would now be deranged as a leader, and would blindly loose an anger that would destroy everything in its path; that would ultimately make his life and office meaningless to the very people who have given him support. None of these will come to pass.”

Media lapped up conspiracy angle feed

In Marcos’s diary entry for Dec. 9, 1972, there is a sentence fragment: “And the story of the confessions on the rightist coup d’etat.” Marcos did not become deranged with anger, he was back to his old calculating self, spinning tales that will enhance his dictatorial powers.

Tatad worked both the crony and the foreign press on the conspiracy angle.

The Associated Press posted on Dec. 9, 1972: “A joint military operation was also reported to have rounded up 85 persons in the greater Manila area in connection with the attempt on Mrs. Marcos, Tatad announced. No details about Dimaali were released and it was not reported if he was connected with the alleged conspirators, whose arrest was announced today. Tatad identified the conspirators as Eduardo Figuerras, Antonio Arevalo and Manuel Crisologo. Other than describing Crisologo as an ‘explosive expert,’ Tatad did not give any more details. Tatad said: ‘Because of incriminating evidence’ linking them to the conspiracy, the following were also detained by the military: Sergio Osmeña, III, oldest son of former Sen. and incumbent Cebu Mayor Sergio Osmeña Jr. The young Osmeña is a grandson of Philippine Commonwealth President Sergio Osmeña. Jesus Cabarrus Jr., executive vice president of the Marinduque Mining and Industrial Corp., who is married to the young Osmeña’s oldest sister. Eugenio Lopez Jr., publisher of the Manila Chronicle and president of its radio and television network. He is also a vice president of Meralco, the power company whose management is controlled by his family. He is nephew of incumbent Vice President Fernando Lopez.”

Not to be outdone, the blaring headline of the Dec. 10, 1972 issue of the Sunday Express said it all: “Osmeña, Cabarrus, Lopez scions held on slay-FM plot; Eddie Figueras, two others confess.”

In three days, Marcos and Tatad managed to shift the narrative away from Imelda and now almost solely on Marcos and those conspiring against him.

Marcos had been talking about threats to his life. On Dec. 27, 1969, a month after he won reelection to the presidency, United Press International quoted him as saying that death threats were “standard hazards of the presidency.” Yet after declaring martial law, Marcos’s propaganda harped on the attempts on Marcos’s life and how all these have failed. The important point being conveyed was the naming of enemies that the dictatorship must go after having threatened the president’s life. On Oct. 18, 1972, the Associated Press reported that “four attempts to kill President Ferdinand E. Marcos this year failed and a fifth was frustrated by alert security men.”

“I am amazed at the plot to assassinate me and its intricacies,” Marcos wrote in his diary on December 2, 1972. “They were even going to use a grenade inside a mike (microphone) I was going to speak through in public and a model plane loaded with liquid explosives to be bumped against me or my helicopter or plane. I attached copies of the sworn statements of Eugenio Lopez Jr., Sergio Osmeña III.”

No such verifiable statement was ever written and sworn to by either Lopez and Osmeña. Without a warrant and any charge, Marcos had the two of them arrested on November 27, 1972. Two years later, on November 18, 1974, they staged a hunger strike. On its ninth day, they were verbally informed by their jailers that in August 1973, charges were drawn against them for conspiring to assassinate Marcos. How could Lopez and Osmeña confess in writing about anything on December 2, 1972 when it was not until two years later were they informed on why they were taken into military custody?

The jailing of Lopez and Osmeña was a squeeze play by Marcos designed not only to do away with his political opponents, but more so to extract from them their wealth and give them away as bonanza to his cronies. This is particularly true in the case of the Lopezes.

But the attempt on Imelda’s life was not only made an excuse to go after the oligarch that he hated, Marcos also used it to implicate the communist insurgents. Marcos had a conspiracy on the right, a conspiracy on the left, and everyone in between was also fair game.

Ver, in his notes, mentioned that on “080825 Dec, Sgt Balmoha of the San Juan detachment received a tel call which was taped—‘Papatayin namin sila lahat.’ A similar call was received by Sgt Sta Cruz at Calixto Dyco detachment.” Ver recommended “that all members of the First Family and immediate relatives be cautioned to undertake precautionary measures and avoid unnecessary public exposure until the situation has stabilized.”

A Dec. 11, 1972, United Press International report had Tatad saying: “The conspiracy included a plan to kidnap Ferdinand Marcos Jr., to force the release of political prisoners and the resignation of President Marcos.”

In the “Eleventh Progress Report re Attempt Against the Life of the First Lady” by the CIS [Criminal Investigation Service] on Dec. 16, 1972, there was already an insinuation that there were people, if not a group, behind Carlito.

On 16 Dec 72, Mr Francisco Dimailig, with her two daughters, Dra Thelma Dimailig and Mrs Sonia de Ala, gave to the CIS an opened letter postmarked ‘Manila 12 Dec 72’ addressed to Mrs Josefa Dimailig in Calaca, Batangas, which they received by mail in Calaca on [15] Dec 72, the contents of which is a poem in Tagalog and Carlito Dimailig is the subject. Efforts will be exerted by the CIS, in coordination with ISAFP, to trace and arrest the author and sender of said letter.

The six-stanza poem tells Carlito’s mother to be proud of what her son did. “Huwag kang malungkot, pahirin ang luha / Itaas ang noo, huwag mahihiya / Ang iyong Carlito’y magiging dakila / Sa kasaysayan ng ating inang bansa.” The poem talks about killing not only Imelda, but also Marcos. “Si Imelda’t Marcos, ugat ng hilahil / Masakit man sa loob, dapat na putulin.” The poem concludes that with Carlito’s sacrifice, “Ang pakikibaka ay muling lalawak.” In between stanzas are crude rendering of the hammer and sickle. Opposite the name of the poem’s author “Commander Ruel Necy” is a raised arm holding an upturned rifle.

Assassination attempt story morphed into revolution in the making

On Dec.14, 1972, a United Press International report citing “official government sources” disclosed that the attempt on Imelda’s life “was part of a Communist urban guerilla plot to attack the presidential palace and other strategic installations. Sources said the plot fizzled out when the knife-wielding attacker failed to kill Imelda R. Marcos . . . Evidence gathered by government investigators, the sources said, indicated that Mrs. Marcos’ assassination was to have been the signal for simultaneous Communist attacks on Malacanang Palace, military installations and vital public utilities. They said the raids were mapped out to take advantage of the ensuing confusion after her killing.”

On Dec. 15, 1972, the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, carrying another United Press International report, had it headlined: “Philippine revolution plot foiled.” “Sources said government evidence on the plot was bolstered by the discovery of a cache of more than 300 high-powered firearms, several rocket launchers, more than 65,000 rounds of ammunition, nine drums of fragmentation grenades and voluminous Communist propaganda materials. The arms, buried in strategic places in metropolitan Manila, were to be used by Communist urban guerillas ‘at a given signal from their leaders’.”

Four years later, on March 29, 1977, Marcos decreed it a crime punishable by death to “attempt on, or [conspire] against the life of the chief executive of the Republic of the Philippines, any member of his cabinet or their families.” Which he further expanded on Nov.11, 1980 to include members of “the Interim Batasang Pambansa, the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Commissions, general officers of major services and commands of the Armed Forces of the Philippines or any member of their families, or who uses any firearms or deadly weapons against the person of any of the government officials enumerated herein, or any member of his family.” Cory Aquino repealed these Marcos edicts saying that the “crime of Lese Majeste has no place in a democratic society.”

It was never proven that Carlito Dimailig was part of any conspiracy.