Originally published by Vera Files on October 24, 2024

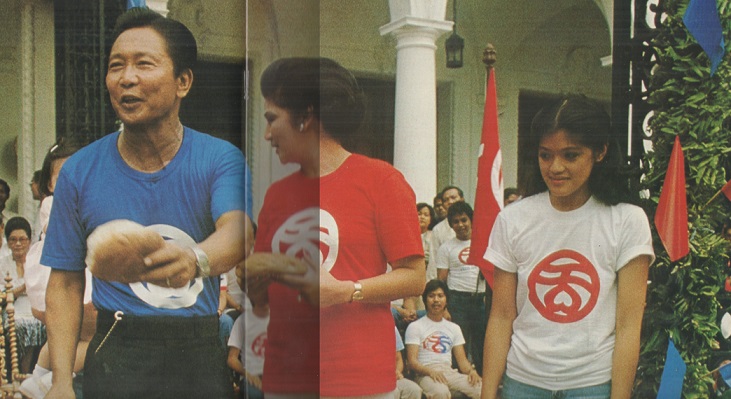

There she was again, wrapped in a red shirt emblazoned with the Kabataang Barangay (KB) logo.

Last October 10, 2024, Sen. Imee Marcos spoke with the media for more than an hour in a forum. She was asked questions mainly about her efforts to get reelected to the Senate and the work she is doing there. No one remarked on why she was wearing that shirt. By now, it has become a part of her political brand: the eternal head of Kabataang Barangay, or KB.

But why was Imee in Kabataang Barangay in the first place?

The last time somebody questioned Imee’s association and leadership of the Kabataang Barangay, that person was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by Imee’s security personnel.

Archimedes Trajano

Archimedes Trajano was a 21-year-old engineering student at the Mapua Institute of Technology (now Mapua University). On August 31, 1977, in a forum supposedly geared toward organizing “school-based Kabataang Barangays,” and with Imee present as head of the Kabataang Barangay, Trajano asked why Imee had to be the person who wielded such power.

This prompted Imee’s bodyguards to drag Trajano away. Imee’s thugs were military intelligence personnel under the command of Gen. Fabian Ver, then director-general of the National Intelligence Security Authority. Ver was Imee’s distant uncle. He was a cousin of her father, the dictator, President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

Trajano “was taken to the presidential palace for interrogation under torture.” This was what Trajano’s mother, Agapita, told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser on March 23, 1986. “Trajano was tortured from 12 to 36 hours.” This was what a pathologist testified before the court, as reported by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin on March 26, 1991. Trajano was later found dead in his boarding house; he sustained multiple fractures and a crushed skull.

One is hard-pressed to find extant news articles regarding his death published around the time that it happened. The only one easily accessible today is in the digitized version of a Singaporean daily. The Sunday edition of the Singapore daily New Nation carried an Agence-France Presse story, dated September 4, 1977, headlined “Student Kills Family of Three,” which cited claims made by the police that Trajano inexplicably killed his neighbors and, inexplicably still, “fell to his death from a third floor ledge while apparently trying to escape.” The article noted that Trajano was the same student who was “picked up” for questioning “for creating a disturbance during a recent public rally in Manila where President Marcos’ eldest daughter, Imee, was guest speaker.”

Agapita Trajano recalled that “government newspapers reported that her son ‘ran amok’.” But she was told a different story: that her son was “in a dormitory fight.” Both she did not believe. For her, the three other people killed in the boarding house were witnesses to what Imee’s men actually did to her son. On September 2, 1977 Agapita retrieved her son’s mutilated body in a Manila funeral parlor.

On March 20, 1986, Agapita filed a civil case in Hawaii against Ferdinand Sr. and Imee. Both Agapita, as an immigrant, and the Marcoses, as exiles, happened to be in that US state then. Evading an earlier federal grand jury subpoena in Virginia, Imee “left the United States just after the Marcoses arrived in Honolulu in February 1986.” Using a fake Bolivian passport, she and her family fled to Morocco, then to Europe. She ignored the Trajano case until a judgment was entered and she was cited as being in default. On appeal, Imee, through her lawyers in the US moved for the dismissal of the case. She lost the appeal in the federal court.

The court found that Trajano was “kidnapped, interrogated, and tortured to death by military intelligence personnel” who were acting under the authority of Ferdinand Sr., Imee, and Fabian Ver. Given the facts as appreciated by the court, the claim that Trajano died after running away from the scene of a crime was evidently a cover-up. Imee was held liable for damages amounting to USD 4.1 million, but due to certain maneuverings, she never paid a cent to Trajano’s mother.

Such is how Imee and the KB are remembered among victims of human rights violations during the Marcos dictatorship. Imee would rather we remember her time as KB head much more fondly, though obscuring precisely when and how she became chair of the youth organization. As with many things in her life of autocratic privilege, Imee’s leadership of Kabataang Barangay was a consolation bequeathed to her by her parent’s conjugal dictatorship.

There is an early profile of Imee in the September 17, 1971 issue of the Asia-Philippines Leader. At 15, Imee claimed that “she will never run for any political post in the future.” She was nevertheless opinionated regarding the decisions of her father. She agreed with her father’s suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in the wake of the August 21, 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing. It was the “last straw,” she said, further stating that the “suspension had long been coming.” In a September 21, 1971 letter to Imee, Ferdinand Sr. called her as his “sweet adorable scramble-brained eldest daughter who claims the temperament of a prima donna and the objectivity of an Oxford Don.”

According to the article, Imee was then in the “5th Form (equivalent to [Philippine] fourth year high school) at the Convent of the Holy Child Jesus in Old Palace, Mayfield, Sussex, England.” A little over a year after that article came out, the Philippines was placed under martial law. Imee was still abroad, a student at the Santa Catalina School in Monterey, California. She later transferred to the International School in Makati and graduated on May 11, 1973 with her father as the commencement speaker. In September 1973, she was enrolled at Princeton University.

Imee failed all of her courses in Princeton

Her ascent toward becoming a well-credentialed daughter of a dictator, supposedly with no political ambitions, hit a snag in mid-1976. In his June 16, 1976 diary entry, Ferdinand Sr. said, “Imee arrives tomorrow [from Princeton.] We have a problem with her as she has lost interest in her studies in Princeton.” Indeed, based on a letter from Paolo Cucchi, assistant dean of the College, West College, Princeton University, dated June 11, 1976, Imee failed all of her courses during the 1976 spring term.

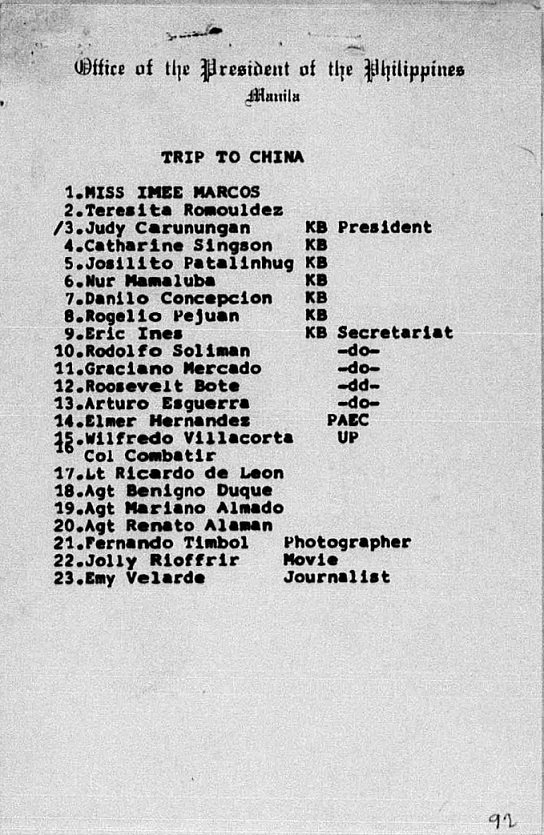

We may send her to Peking,” Ferdinand Sr.’s diary entry continued; “The Chinese will think we are trying to get into their good graces. But she will be there when Mao dies and a violent factional conflict develops.” She was indeed sent to China, but about a year later, after Mao Tse-tung had died. She left for China on June 21, 1977 and returned to Manila on July 18, 1977. Afterward, she was briefly enrolled in the University of the Philippines (UP) as a non-degree student, acted in local theater productions, and, most importantly, given her first public position: a leader in the KB. Oddly, in a list prepared by the Office of the President of KB members who went to China for the study tour, Imee was not even identified as an officer of the organization.

Overage for KB

Imee’s official biography claims that she chaired the KB from 1975 to 1986. She did not. The KB was indeed established on April 15, 1975, via Presidential Decree 684. The first KB elections were held on May 1, 1975. Those eligible to be part of the organization “shall be at least fifteen years of age or over but less than eighteen.” Imee was then 19 years old, Bongbong was 17.

Imee was not associated with the KB prior to her return from abroad in 1976, nor was she immediately made one of its leaders. Ferdinand Sr. may have even been considering another political heir to rule over KB. On July 20, 1975, in a leadership training graduation of around 800 Kabataang Barangay members in Mt. Makiling, Ferdinand Sr. spoke of how “the New Society will be handed down as a noble legacy to the young” through the Kabataang Barangay. Bongbong, yet to start his failed attempts to obtain a Philosophy, Politics, and Economics degree in Oxford, was the one with him.

As Imee was failing in Princeton University and slouching towards Malacañang, the first President Marcos issued Presidential Decree 935 on May 15, 1976. It suspended the age limit (below 18) of members in youth organizations “to allow the Kabataang Barangay officers to continue in office.”

And then on February 28, 1977, Imee’s father, as a dictator ruling by decree, issued Presidential Decree 1102 specifying that only those “twenty-one years of age or less” can be a member of the Kabataang Barangay. Imee was then 21 years, 3 months, and 16 days old. (Note that Ferdinand Sr. also enacted Batas Pambansa 52 in 1979, lowering the age requirement from 23 to 21 for local candidates to accommodate Bongbong’s ascendance to the vice-governorship in Ilocos Norte on January 4, 1980)

But there remained nagging questions on Imee’s KB takeover. From which barangay was Imee a member of KB of and from which KB council was she elected to? Which municipal or city federation voted for her to lead the provincial federation? Which provincial federations voted for her to lead the regional federation? Which regional federations voted her into the national one and finally who voted her into office as KB’s national chair? If you have a father as dictator, such questions are superfluities.

An article in the November 25, 1976 issue of the Philippine Collegian noted that Imee was in UP partly “to observe the Kabataang Barangay unit [there],” but did not refer to her as a KB leader. The article quoted Imee as saying that she was unhappy about “‘many things’” regarding the implementation of martial law, such as “the state of civil liberties, the treatment of labor strikes, and the muzzled press.” If that made her sound like a critic of her father’s rule, that is precisely how she wanted to appear; “My relations with the President is surprisingly frank, verging on rudeness. My father once said, referring to me, that the greatest subversive is in Malacañang.”

Imee as KB national chairman?

The supposed subversive was formally given a role in the KB sometime in 1977. A 1978 UNESCO working paper on the KB by Dr. Wilfredo Villacorta—who was with Imee and the KB leaders during their China sojourn—claimed that after she “involved herself more actively in the movement,” Imee “officially became [KB’s] national chairman” in 1977. Villacorta also noted that KB, which was under the Ministry of Local Government and Community Development, then became a body under the Office of the President. Another source, a profile of Imee in The Straits Times, published on June 5, 1977, notes that her involvement in the KB, “of which she is currently national chairman, has been recent.” “Asked how she became involved with the movement…[Imee said]: ‘My father thinks very highly of the KB. He used to keep telling me about their wonderful achievements….If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. So there I am.”

A less flippant version of Imee’s rise within KB is told in the pages of We Forum, particularly its June 16-30, 1977 issue. Written by Chuchay Molina, the article titled “Who is really running the Kabataang Barangay?” noted that Imee had referred to herself as a “‘mascot’” of the KB, an “‘honorary everything,’” not the KB’s national chairman. But the article also noted that at that time, the national chairmanship of the KB was vacant, since the elected national chairman had resigned in February 1977, and its national vice-chairman had been suspended. Imee was seemingly the de facto head of the organization.

A declassified US Department of State cable, dated September 20, 1977, subject: “Weekly Status Report – Philippines,” makes reference to a “young Filipino who was national president of the Kabataang Barangay (youth organization) until supplanted by Imee Marcos.” According to Molina’s 1977 We Forum article, the KB national chairman who resigned earlier that year was Bernardo Tensuan.

Molina wrote a follow-up article, “Who’s Really Running the KB?—Part II,” published in the May 6-12 issue of We Forum. She noted that a year after her last KB article, and shortly after the April 1978 Interim Batasang Pambansa elections, which included the election of youth representatives, Tensuan told her that “since he resigned last February 14, 1977, there has been no recognized chairman in his stead.” Tensuan claimed that the national KB was run by its National Secretariat (NASEC), which Molina noted was run by “much, much older coordinators,” and that the “NASEC” was only supposed to be an implementing body. In his paper, Villacorta noted that the Secretariat supports the regional KB federations and “grass-root membership.”

KB Foundation, not KB

Reliable sources show clearly why it has never been entirely factual to state that Imee was the chairman of the KB national organization—she chaired what was called the Kabataang Barangay Foundation, Inc. The decree creating the KB does not mention a KB Foundation. The first statute to define the role of the foundation, in relation to what was called the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Kabataang Barangay ng Pilipinas or PKKB, was PD no. 1191, enacted on September 1, 1977. The decree gave some measure of autonomy to the PKKB, as the earlier KB-related decrees charged the Secretary of Local Government and Community Development to “promulgate such rules and regulations as may deemed necessary to effectively implement the provisions [of PD no. 684].” Whereas the PKKB chairman was elected from among the presidents of regional KB federations, the law was silent on the selection of the KB Foundation’s Board of Trustees. The foundation released and administered the funds annually appropriated for the PKKB. Effectively, as KB Foundation chair, Imee had the power of the purse over the most significant source of KB funding.

And as noted by Jose L. Burgos Jr. in his “Now and Then” column in the March 1, 1986 issue of Ang Pahayang Malaya, Imee was indeed her parents’ daughter. “I am not a bit surprised that the Marcos children were able to accumulate wealth of their own during the regime. I remember that early during the martial years, after the Kabataang Barangay [Barangay Youth] had been established, then Imee Marcos used to collect money from the cities and towns of Metro Manila by the millions. Quezon City, Manila, Makati and perhaps Caloocan and Pasay used to give her checks for millions of pesos which were never accounted for. I used to see some of those checks given her by Quezon City.”

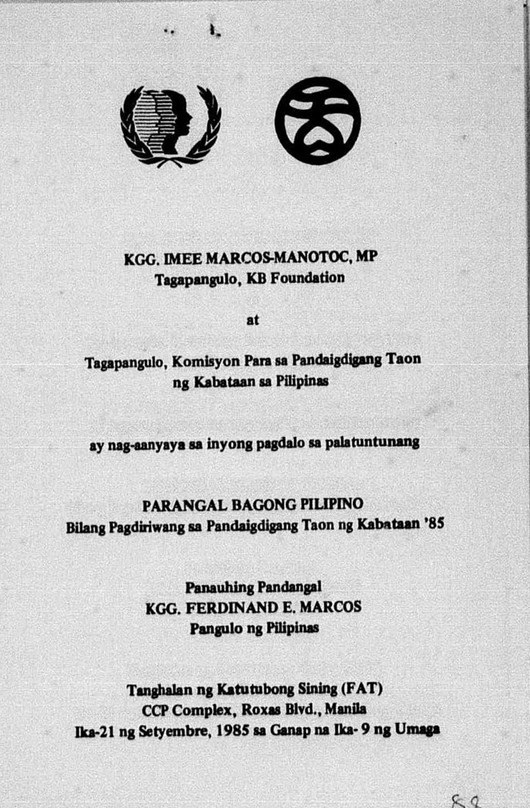

Marcos Sr. expanded the roles of his daughter’s KB Foundation via executive orders. For instance, EO no. 887, s. 1983 made Imee, as chairman of the KB Foundation, the head of the Philippine Commission for the International Youth Year. That EO amended an earlier one, EO no. 795, s. 1982, which named “the Chairman of the Kabataang Barangay”—without “Foundation”—as head of the subject commission. A 1981 order, EO no. 734, tasked the KB Foundation to handle the release of government funds for the Kilusan sa Kabuhayan at Kaunlaran ng Kabataan program.

In the late 1970s until the early 1980s, despite her command of the KB, Imee continued to claim that she did not want to follow in her father and mother’s footsteps. Her June 1977 Straits Times profile quoted her as saying, “My ambition is everywhere except in politics. I think I want to be a lawyer of sorts when I return to Princeton in September.” She did return to Princeton in September 1977, but went home in 1979 without having completed a bachelor’s degree.

Her Princeton failure had no effect on her leadership of the KB (Foundation). She became synonymous with KB, even when certain leaders of the movement appeared opposed to certain government thrusts. A burning issue in 1978-1979 was the extension of the US-Philippines Military Bases Agreement. Imee was among the signatories of an August 1978 open letter from the KB against the renewal of the agreement. According to news accounts, the letter included lines such as, “[these] military bases are clear evidence of our being American stooges because they represent foreign interests.”

According to a declassified US Department of State cable, dated August 9, 1978, US Ambassador Richard Murphy talked to Marcos about the letter. Marcos said that he “asked his daughter…what she thought she was doing signing such a letter, asserting that he had been unaware it was in works. Imee replied that she had signed the letter, which she recognized reflected [the] sentiment of [the] radical wing of KB on bases, because in her opinion it was better to hold KB together and keep radicals within [the] organization rather than drive them to agitate outside of KB.”

Using KB as leverage in bases negotiation with U.S.

It was all for show though and a seeming bad one at that. Ross Marley, an associate professor of political science at Arkansas State University, writing for the journal Pilipinas in 1985 pointed out what it was all for. “Marcos is also capable of flirting with the U.S.S.R., but as Filipinos say, it is only palabas (for show), as when he told reporters that if the U.S. Congress didn’t want to pay the rent he was asking for the air and naval bases, he might offer them to the Soviets. American diplomats understand that this is only for the newspapers. Another ploy was to have daughter Imee lead the Kabataang Barangay youth corps in a demonstration against the presence of the bases, an exercise which did little to move the American negotiators or to legitimize the KB in the eyes of Filipino nationalists. The campaign was soon dropped.” When the new basing agreement was signed in Malacañang on January 7, 1979, who else was standing behind President Marcos as he inked the pact but the “subversive,” Imee.

A profile of Imee, written by Marra PL. Lanot for the March 7, 1982 issue of Philippine Panorama, continued to call her “head of KB,” a role for which she “rode helicopters and visited schools and youth centers in white T-shirt and blue jeans, her Farrah Fawcett hair flying in the wind.” The piece also mentioned that she was studying law in the University of the Philippines and headed the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines. Despite her many hats and public visibility, she continued to claim that she would not be gunning for an elected position in the future. Lanot asked if she would she go into politics. In response, Imee said, “Well, that’s a bit redundant. I mean, being Marcos and all that sort of thing. Nakakaantok na.”

It might have been something to yawn about for Imee, but in her father’s machinations to never loosen their family’s grip on power, Imee was always a valued pawn.

The August 16, 1982 issue of the Official Gazette, in its “Official Weeks in Review” section, reported that on June 8, 1982, “President Marcos said he liked the idea of letting leaders of the Kabataang Barangay sit on rotation basis as observers in the executive committee which runs the government on a day-to-day-basis. The Kabataang Barangay, in its national congress held in Malacañang’s Maharlika Hall, had asked for permanent representation in the seven-man executive committee, proposing that KB Chairman Imee Marcos be the representative. The President replied that this could not be done because he would be accused of setting up a dynasty.”

Again, as with the US bases, it was all for show. As reported by Agence France-Presse, in an article that appeared in the the July 13, 1982 issue of the South China Morning Post, Imee was designated “a member with observer status of the country’s seven-member cabinet executive committee.” The article noted that the committee was meant to be a “‘collective successor’ should anything untoward [happen] to the President.” However, according to another SCMP article, in September 1982, Imelda said that Imee “resigned all her Government posts” in order to “finish her law studies.”

At the time, unknown to the public, Imee was pregnant. Seven months later, on April 9, 1983, she had her firstborn at Kapiolani Children’s Medical Center in Hawaii, Fernando Martin “Borgy” Marcos Manotoc. Imee married Tomas “Tommy” Manotoc in a civil ceremony in Arlington County, Virginia on December 4, 1981.

Fake graduation ceremony

Fifty days after giving birth, on May 29, 1983, a ceremony was staged to make it appear that Imee graduated from the UP College of Law. Imee did not and could not graduate from UP with a law degree. Having failed Princeton University, Imee has no college degree. Yet the UP College of Law allowed her in as a regular law student despite its supposed stringent admission requirements. The University of the Philippines, however, could not simply gloss over this glaring deficiency and grant her a law degree in the end.

In October 1982, Marcos issued another KB-related order, EO no. 841, which created (or perhaps formalized or redefined the roles of) a Kabataang Barangay National Secretariat, intended to “serve as the staff support” for the PKKB. The KB secretariat was headed by an “Executive Director who shall be appointed by the President of the Philippines”; Imee was not the secretariat’s director, but she continued to be head of the KB Foundation, the one position she is known to have never relinquished.

Nurturing patronage politics

According to an article by Margarita Logarta, which appeared in the October 26, 1983 issue of the magazine Who, the KB executive director was a Miles Millena. An Edward Chua of the KB National Executive Committee told Logarta that “Imee still heads the movements which includes the elderly leaders in the community who could support the organization in the attainment of our objectives.” Roger Peyuan, then a member of parliament and a former KB federation president, added, “[Imee] has taken the cudgels many times in our behalf. She would personally write officials asking that our proposals be granted or to cure some anomaly.” It thus seemed that Logarta was justified in calling Imee the KB’s “most tireless campaigner,” even if it remained difficult to show where she was exactly in the KB’s organizational structure.

Or viewed differently, like a fungal spore that latched on a moist, dark place, Imee, through the KB, spawned her own kingdom of petty corruption and patronage. Those that benefited from it, those who gained their leadership skills through the Kabataang Barangay, or even those who would like to look back on their KB days as days of youthful joy and camaraderie, these are the people that Imee hopes to still endlessly lure into voting her brand. The very same generation who thought that Imee and KB became one and the same—which clearly, they were not.

Of those who thought of Imee as KB boss during the dictatorship, many have gone on to hold prominent government positions. These include former Quezon City Mayor Herbert Bautista, current Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro, former University of the Philippines President Danilo Concepcion, and Marilyn Barua-Yap, recently appointed by Bongbong as ad interim chief of the Civil Service Commission. Next year, just before the elections, they will likely commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Kabataang Barangay, with their senate reelectionist “founding chair.”