Originally published by Vera Files on October 3, 2024

After hearing the harrowing story of a survivor during last month’s national summit on combating online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (OSAEC), a visibly-moved President Marcos said he could not help but shed a tear.

“Accompanying those tears that I just shed,” he said, “was a deep sense of shame because we have not done enough for the Philippines to now be considered the epicenter of—let us not shorten it into a clinical term, OSAEC—it is sexual abuse and exploitation of children.”

The president’s sense of shame should be deeper because his parents, former president Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and former first lady Imelda Marcos were the originators of sexual tourism in the country.

Burgeoning sex trade

In the 1970s, the Philippines had a population of around 40 million, of which, “20,000 [were] rest and recreation entertainers and the rest of the 300,000 hospitality girls, massage and bath attendants, performers in sex shows, hostesses and waitresses,” a third of whom worked in Metro Manila, Pennie Azarcon-de la Cruz wrote in Filipinas for Sale (1985).

These numbers were known because the Marcos government, through changes in the Labor Code and in the functions of the Bureau of Women and Minors, kept tab of those engaged in sex work. Hence the Marcos administration knew exactly what it was doing.

Azarcon-de la Cruz pointed out that, “despite the government’s reluctance to admit a burgeoning sex trade, a Manila ordinance requires these girls to submit to periodic health check-ups before they are issued government permits as employees of the hospitality industry. Hostesses, hospitality girls and massage attendants are required to secure the Mayor’s permit, NBI and police clearance, professional license and health certificate before they are allowed to work (Ordinance 2961 and 3000).”

The annual tourism receipts in the hundreds of millions of dollars hardly made a dent on the enormous debt that the government incurred in simultaneously building 14 luxury hotels that Marcos cronies benefitted from. The list of new resorts, golf courses, museums, and “beautification” projects was both for flaunting political patronage as it also became the record of the urban poor’s and the indigenous peoples’ dispossession and loss. Marcos’s reliance on the tourism industry for cash and legitimacy would later on invite fires and bombings from those opposing his regime.

This seamy past was brushed away during the Department of Tourism’s (DOT) 50th anniversary on June 27, 2023 at the Manila Hotel’s Tent City where Tourism Secretary Christina Frasco handed the president a “ginintuang pasasalamat at pagpupugay,” for his late father’s “instrumental contributions to the Philippine tourism industry, primarily the creation of the Department of Tourism 50 years ago.”

For his part, the president affirmed in his speech his father’s vision in creating the DOT. “Indeed, the potential of the tourism industry as an economic pillar was well seen by my father when he established the Department of Tourism in 1973,” he said.

Joe Aspiras, father of Philippine tourism

As he continued his speech, Marcos ad-libbed to acknowledge “the family members of Manong Pepito, Joe Aspiras, who was the first secretary of tourism upon the creation of the department.” The only former DOT secretary that the president mentioned by name in his speech.

Aspiras served as Marcos’s tourism secretary (later minister, when Marcos shifted the form of government to partly parliamentary, semi-presidential in 1978) from the time that the DOT was established on May 11, 1973 until the Marcoses fled to Hawaii on February 25, 1986 as they evaded the People Power Revolt. At almost 13 years, he is the longest-serving DOT secretary. Before that, he was press secretary during Marcos’s first term as president (1965-69). Aspiras ran for office in 1969 and became the representative to Congress of La Union’s second district until 1972. He was also a member of the Interim Batasang Pambansa. After Marcos, he continued to represent La Union in Congress from 1987-1998. He died in 1999.

Given Frasco’s and Marcos’ lofty recollections, what did Aspiras and Marcos Sr. actually do for Philippine tourism during the martial law years? Was it something deserving of a plaque, “golden in tribute and gratitude”?

Narzalina Z. Lim, writing in Women on Fire (1997), recalled that she “used to march with my women friends past [the Ministry of Tourism] on T.M. Kalaw Street and Rizal Park to protest the organized sex tourism which flourished in the late Seventies and early Eighties, which was clearly condoned, if not encouraged, by the ministry.”

For Lim, the tourism ministry that Marcos Sr. formed, and Aspiras led, “was used by the Marcoses to window-dress the stench and corruption of their regime.” Lim would later serve as DOT secretary in the Aquino and Ramos administrations. She was not at the DOT’s 50th anniversary event.

When Marcos Sr. formed the DOT via Presidential Decree 189 on May 11, 1973, of the four whereas clauses, the reasons for the decree, three were on issues of administration and governance and one stands out which in due course would be the main concern of the DOT—it’s the whereas clause that is all about the money. There must be a DOT because “the tourist industry will represent an untapped resource base toward an accelerated socio-economic development of the Philippines.”

Gregorio Araneta II, commissioner of the pre-DOT Board of Travel and Tourist Industry, reported in the 1972 Fookien Times Yearbook that in 1971, there were 144, 321 visitors to the Philippines. “Americans have, as usual, been our No. 1 arrivals totalling 64, 740 . . . with the Japanese taking second place at 23, 539 arrivals. Ranking third are the Australians totaling 12, 415.”

Araneta attributed this dismal record to the Philippines’s negative image abroad, limited flights per week to Manila, and the high cost of airfare. For the first factor he attributed this to “peace and order, unfavorable publicity overseas, sensational reportage of crime, dirt and poverty, sanitation, garbage collection, bad state of roads, lack of information on the Philippines abroad due to budgetary limitations.”

It was as if the whole tourism industry was just waiting for Marcos’s martial law for it to take off, the same way that the martial law regime’s New Society needed tourism’s “Where Asia Wears A Smile” slogan to mask its depravities.

“What has happened since the declaration of martial law to stimulate tourism arrivals from 144,321 in 1971 to over one million in 1980,” Linda K. Richter argued in her book Land Reform and Tourism Development (1982), “simply cannot be explained as a response to artificially suppressed demand. Rather it reflects a political program of the utmost seriousness implemented with an almost cavalier disregard for the economic costs of such an endeavor. That tourism was chosen as one of the most important props of the new order is indicative of the imagination as well as the vanity of the New Society.”

One of the regime’s own publications, The Philippines (1976), said political program was translated into the following: “Hotel-room taxes have been abolished. Crimes against tourists are now tried by a military tribunal. An ‘open-skies’ policy allows airlines with reciprocal agreements with the Philippines to operate an unlimited number of flights to Manila. Visa requirements for a stay of up to two weeks have been lifted and special entry privileges now await visiting businessmen and investors.”

Dollars at the expense of reputation

A year into office as DOT secretary, Aspiras, wrote in the 1974 Fookien Times Yearbook that “the Philippine tourist industry today is in an unprecedented high state of stimulation, animated by a dramatic surge of growth in 1973 and keyed up even further by visible signs of a promising future . . . Measured in terms of visitor arrivals and their expenditures, last year’s increase was phenomenal. The 242,800 tourists who visited the Philippines in 1973 represented an increase of 46 percent over 1972—against an average annual growth rate of 10 percent in the preceding ten years . . . . In 1973 tourism ranked as the fourth largest dollar earner for the Philippines, next only to such traditional exports as logs and lumber, copper and sugar.”

At its peak in 1980, with one million annual visitors, tourism’s receipts for that year amounted to USD 420 million. It was third in terms of earning dollars for the country, the tourism ministry would claim.

But Aspiras himself provided a caveat in their computation. In his report in the 1979 Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook, he conceded that the Central Bank “calculates strictly on the basis of what goes through the banking system while the MOT bases its own estimate on the assumption that each tourist spends about $49 daily on average stay of eight days.”

Aspiras may not be wholly certain of how much money the tourism industry was making for the country, but whom to credit for such an appearance of success he was without doubt.

“[T]he active participation of President Marcos and the First Lady, Metro Manila Governor and Minister of Human Settlements Imelda Romualdez Marcos in world affairs gained for the country an international stature . . . The heavy influx of foreign visitors to the Philippines has become virtually the expression of acceptance and endorsement of the political, economic and social reforms brought about by martial law,” Aspiras wrote in the 1981 Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook.

To earn this much dollar and beckon this many tourist meant trading Filipino bodies for cash—and this Aspiras knew. Two years into his post as secretary of tourism, Aspiras had to battle the sordid reputation that Manila gained as the “flesh capital of the Orient.”

In a March 9, 1975 Associated Press (AP) report in the Hawaii Tribune-Herald, Aspiras, was quoted complaining about “malpractices in the hospitality industry,” by which he meant “‘free wheeling sex’ in some hotels and other tourist establishments.” If Aspiras would only have his way, he wanted to “change this growing negative image. It is time we emphasize the cultural, historical, scenic and other attractions aside from base pleasure.”

Because of Aspiras’s supposed displeasure, the police, from January to March 1975, “have rounded up 600 suspected prostitutes and pimps in the tourist belt.” The last raid “resulted in the arrest of 206 suspected call girls and their procurers.” The AP report noted that “in 1973, the first full year of martial law, only two girls were arrested on charges of prostitution.”

Proliferation of Japanese sex tours

The link between tourism and the flesh trade was made plain by the police. The AP report extensively cited Capt. Vicente G. Vinarao, then chief of Manila Police Special Operations Division. “Vinarao said pre-paid tours, which some local travel agencies negotiate with foreign partners, particularly Japanese, usually included ‘a night with a girl’.”

“He said under the arrangement, a tour agency would send about 50 tourists to a cocktail lounge. ‘There they pinpoint any girls they want. These girls are booked in the hotels as guests or friends of the tourists.”

“We have informants in hotels so we know who to pick up. But we usually arrest a girl when the tourist-customer is not around. We don’t want to embarrass our visitor. Oftentimes, we pick up a girl emerging unescorted in a hotel lobby in the early morning hours.”

Vinarao’s qualm in offending lecherous foreign tourists and the intermittent police action that it led to was characteristic of the ways the Marcos’s dictatorship condoned and profited from prostitution until it was no match to what by then had become mass sex tourism.

One particular incident showed clearly how complicit the tourism industry was in the sex trade.

Ikuo Anai of Reuters reported in the July 1, 1979 issue of the San Francisco Examiner: “The sex tour business achieved a new prominence in Japan after a respected national newspaper [Yomiuri Shimbun] published a report detailing a ‘sex auction’ at a Manila hotel [Ramada Hotel]. According to the paper about 200 Philippine ‘hospitality girls,’ each one wearing a number, were offered to 100 visiting Japanese at the price of $60 each.” The event involved dealers for the Japanese electronics company, Casio Computer.

Of the $60 price, “she gets a little more than $5 of the fee,” A. Lin Neumann penned in the February 1984 issue of Ms. magazine. The rest of the money was divvied up among the “club owner, the tour guides, and the tour operator, with a few dollars thrown in for police protection.”

A November 11, 1979 Associated Press story quoted a “former Philippine tourism ministry official,” that an estimated “2,000 prostitutes in Manila are catering solely to the Japanese.”

Japanese publishers that specialize in adult content, like Sanwa Publishing Co., came up with Tengoku Hyoryu (Drifting in Paradise). The subtitle tells all: “Guide for the Night Life of Nymphomaniac Filipinas.”

Additional numbers can be gleaned from an August 5, 1979 Times News Service report: “Travel agents offer packages at $300 to $400 for four-day excursions to Manila, which drew 172,000 Japanese visitors last year, of whom well over 80 percent were men. The overwhelming majority went ‘for pleasure,’ according to immigration bureau records, not business.”

“It is called baishun tsuaa,” Donald Kirk wrote in the November 4, 1979 issue of San Francisco Examiner. “Or a prostitution tour by Japanese travel agencies and is one of the most popular packages they offer. Almost any travel agent here will book a tourist for three to five days in Seoul, Taipei, Manila, Hong Kong or Bangkok for a fixed fee that includes an evening with an ‘escort’ hired to keep the customer satisfied for the rest of the night . . . Charges of ‘sexual imperialism’ often appear in the newspapers of Seoul and Manila, and government officials occasionally pledge to stop the more blatant forms of whoring. The fact is, however, that the bait of young flesh at prices a third or a quarter the going rate for similar services in Tokyo has done wonders for the tourist trade throughout the non-Communist countries of Asia.”

As Kirk had noted, the government mouthpiece in the censored press, like the Philippine Daily Express, would indeed pontificate against Japanese sex tours in Manila but would undercut such bluster with a remark that maybe the Japanese tourists should just pay more. In an excerpt of their editorial reprinted in The Pacific Daily News in its November 1, 1980 issue: “There is no denying that the country needs as many tourists as our facilities can accommodate. But if it means turning Manila into one sprawling sex haven for them, then a re-examination of our tourism policies is clearly imperative. While we howl over obscene billboards and lewd shows in some of our eateries, the tourist belt is being transformed into one big sex market where sexual favors are nightly sold, and for a pittance at that.”

Filipino and Japanese women jointly campaigned to stop sex tourism

It was the women, both Japanese and Filipino, who in solidarity campaigned to shame the Japanese men and the Japanese government to put an end to mass sex tourism.

“A Japanese government clamp-down on for-men-only, prostitution-pornography package tours to Southeast Asia has resulted in a drastic decline in the number of visitors to the Philippines,”

Andrew Horvat wrote for Southam News on June 29, 1981.

“Japanese tourists, whose numbers had increased from 22,000 in 1972 to 260,000 in last year, dropped 25 per cent in one peak month alone.”

As a consequence, Aspiras wrote in the 1982-83 Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook that “the Ministry of Tourism and the private sector in the industry saw it fit not to rely heavily on the Japanese market.” Despite the downturn, Aspiras noted that the “Japanese continued to dominate the number of tourists who came to the country in 1981 with 193,146 arrivals, chalking up a 10.57 per cent share of the aggregate market.”

The Japanese men who continued to come for their sexual gratification learned to skip Manila and went to other locales, like Cebu. Those who claimed to have clout with Marcos himself even tried building their own sex colony.

Plan for a nudist colony in Mindoro

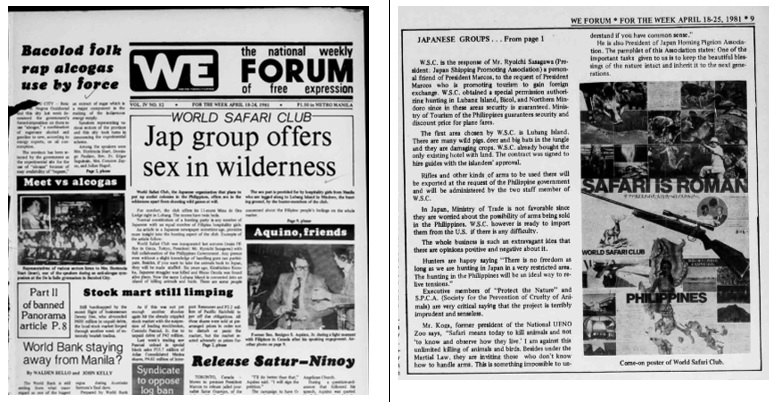

The April 11-17, 1981 issue of the We Forum broke the news that the World Safari Club in Lubang Island in Mindoro, a hunters’ club exclusive to Japanese tourists, was planning to put up a nudist colony.

We Forum, quoting from a brochure in Japanese advertising the World Safari Club, reported that the club “was organized by . . . President Ryoichi Sasagawa at the request of President Marcos who is eager to promote tourism in the Philippines!” As profiled by the Central Intelligence Agency, Sasagawa was a convicted war criminal that managed to rehabilitate himself by becoming a “gambling (legal) czar, right-wing leader, political broker and a modern philanthropist.”

In its brochure, the World Safari club hinted at selling sex to its patrons, of it being able to provide “private companions,” which the Japanese tourists may decline if not to their liking.

A week later, in its April 18-24 issue, the We Forum’s frontpage headline was as forthright as it could be: “Jap group offers sex in wilderness.”

Citing an article in an unnamed Japanese newspaper, We Forum gave more details to what the World Safari Club was doing in Lubang Island. “The sex part is provided for by hospitality girls from Manila who are tagged along to Lubang Island in Mindoro, the hunting ground, by the hunter-members of the club.” And the would-be Japanese members need not even be an actual hunter. “Any person without a slight knowledge of handling guns can participate.”

As if the sex and the hunt were not enough, the article quoted by We Forum also appealed to the prospective member’s sense of history. “Six years ago, Kinshichiro Kozuka, [a] Japanese straggler was killed and Hiroo Onoda was found alive there. Now the same Lubang Island is converted into an island [for] killing animals and birds.”

The article was quick to add that the World Safari Club’s activities had the “full collaboration of the Philippines Government.”

Pedophile capital of the world

By the 1980’s, as stories of mass sex tourism faded from the foreign press, a new blight emerged. News reports identified the town of Pagsanjan in Laguna as the “pedophile capital of the world.”

In November 1983, the Australian police busted a pedophile ring in Melbourne, the Australian Pedophile Support Group. Among the illicit items confiscated from the group were “obscene pictures of Philippine children and discovered plans to bring Philippine boys to Australia,” William Branigin wrote in his December 29, 1983 Washington Post Service report.

A later report from the Australian newspaper The Age on August 22, 1985 indicated that the Australian police informed Philippine diplomatic officials in Melbourne that the pedophile group in Australia was “internationally linked with groups in Sweden, West Germany, the US and Canada.”

“Pagsanjan’s infamy is far flung.” Another report in The Age on March 30, 1985 noted that “paedophile journals throughout the world; journals like the Australian Support Group for Paedophiles newsletter, the French paedophile ‘Desert Patrol’, and its Dutch counterpart ‘Spartacus’,” were all carrying accounts of sexual exploitation of Pagsanjan’s children.

As a tourist site, the Marcos government promoted Pagsanjan for its falls and white-water rapids. But as The Age reported on March 30, 1985, the foreign tourists it hosted (500 on weekdays, 2000 on weekends, for a town with 29,000 inhabitants) “have come for another reason: Pagsanjan’s children.”

The Age reported in August 22, 1985 that “children can be procured for sex for $25 and girls as young as nine have been treated for herpes and other sexually transmitted diseases.”

Nigel Smith of The Age wrote on March 30, 1985: “[Child] prostitution is so widespread in Pagsanjan that it has become the town’s main industry. Its opponents estimate about 3000 children, mainly boys, are regularly sold for sex: a staggering proportion of the juvenile population. More than half the townspeople are dependent on the income generated by the traffic in young bodies that has dominated economic life there for more than a decade. Known locally as pom-poms, the paedophiles’ objectives, some as young as four years old.”

The Marcos government did try to combat child prostitution. When Australia handed it a list of known pedophiles, it promised to bar the entry to the Philippines of anyone on the list. It also enforced a ban on “unauthorized travel by minors who are not accompanied by parents or legal guardians,” William Branigin reported.

In general, the Marcos government simply wouldn’t want to be reminded of the problem. According to A. Lin Neumann, “a series on the phenomenon was slated to appear in a prominent Manila daily. It was killed, reportedly, after the First Lady made the editor aware of her displeasure with the first installment of the exposé.”

Sweeping under the rug a shameful past does not ennoble the present acts even when washed with tears.