Originally published by Vera Files on April 1, 2023

It was an April Fools’ day story that played out in the pages of the Bangkok Post 50 years ago, but the ending lies buried among the papers that the Marcos family left behind when they fled Malacañang in 1986.

It was a farce where the dictator, Ferdinand E. Marcos, put to work government officials and members of the country’s diplomatic corps to refute what was already an open secret: his sexual dalliance with American actress Dovie Beams.

There were three items related to the Philippines in the April 1, 1973 issue of the Bangkok Post. On page 14 was a whole-page profile of Marcos written by the editor-in-chief, Theh Chongkhadikij, with a sidebar on how Filipinos were faring under martial law. So far so good, Chongkhadikij reported, calling Marcos “a deep thinker with fair visions.” Just a page over was a report on Manila’s burgeoning underground press, “reflecting the Filipino’s frustration with stringent press controls after (the) declaration of martial law.”

The Dobbie Beams story

But what would get Malacañang’s goat was an article on the last page with the headline, “Actress Promises Raw Intimacies, Lurid Facts of Oriental Love.” Written by Gerry Coffey, it recounted the supposed efforts of “American actress Dobbie Beams” to publicize in Thailand an upcoming book on her “tempestuous affair” with Marcos.

The piece was accompanied by a picture of a woman, who could have been the real actress, posing as the “Dobbie Beams” that Coffey was referring to in her piece. It hewed so close to tales about the philandering president —as close as Dobbie to Dovie or Dovey— that the bricolage Coffey wrote could have been, to the humorless, mistaken for a report on an actual sex and political scandal.

Later, Coffey would describe her piece as an April Fools’ gag.

In the article, Coffey made it appear that “Dobbie Beams” was doing a promotional tour of the imaginary book in Bangkok “because of its importance in the Southeast Asia region and the impact of her story on the lives of the Asian people.” It seemed a subtle way of saying that the whole region was already in on the gossip about the Marcos-Beams affair — at a time when the president was trying to project his nearly seven month-old martial rule as a steadying factor in the Philippines and a welcome development in Southeast Asia.

By this time, the Bangkok Post had already earned Marcos’s ire when the newspaper published a three-part series, from February 21-23, 1973, of the scathing condemnation of the Marcos regime by Ninoy Aquino, the dictator’s arch political rival. The Aquino Papers, which were smuggled out of the former senator’s prison cell, forced Marcos to answer the tirade with an 8,000-word cable to the Bangkok Post, which the broadsheet also published.

Coffey, who had press access to Marcos and his wife, Imelda, at least twice before, had caricatured the first lady for a bizarre denial of her husband’s alleged long-time affair with Beams.

The incident was obviously preying on the mind of Mrs. Marcos too, for when I interviewed her, she seemed compelled to mention it although I would never have broached the subject myself.

She decried the villainous smear on her husband’s morals and said that their ambitious enemies would stop at nothing to lower her husband’s image in the eyes of the country.

The tape recording, which allegedly had been hooked up under a bed during a clandestine meeting between the President and Miss Beams, reportedly has President Marcos whispering sweet nothings, singing love songs, and reciting poetry.

In actual fact, said Mrs. Marcos, tears threatening to spill down her cheeks, it is an imitation of her husband’s voice taken from his many campaign speeches. The singing, she admitted, is actually that of her husband’s, but any Filipino would immediately recognize that he is singing the national marching anthem—hardly a love song.

Marcos’s men were quick to sense the damaging implications of Coffey’s attempt at humor at the expense of the first couple.

Cleaning up the mess

Four days after April Fool’s day when Coffey’s article came out, the Malaysian newspaper Berita Harian carried an article about Manuel Yan, Philippine ambassador to Thailand, lodging a diplomatic protest at the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs because of the Bangkok Post’s “false story”.

Why Yan, still under 10 months in his posting in Thailand, thought a formal protest was a proportional response to Coffey’s article is unclear. He had a long and distinguished military career, capped by an almost four-year stint as the youngest chief of staff of the Armed Forces at 48. Yan’s diplomatic assignment, however, was largely seen as a way of easing him out from the president’s inner circle for publicly saying that Marcos had no clear reason to impose martial law.

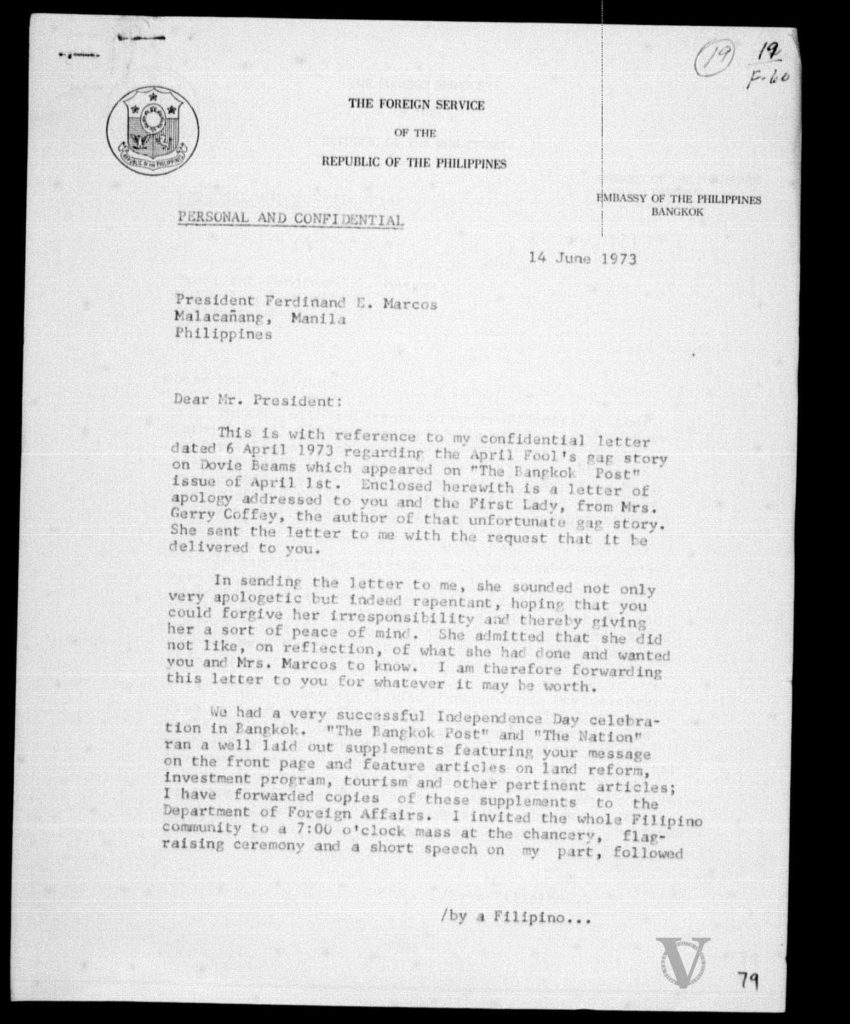

In a June 14, 1973 personal and confidential letter to Marcos, Yan mentioned another letter he wrote to the president on April 6 that same year “regarding the April Fools’ gag story on Dovie Beams which appeared on ‘The Bangkok Post’ issue of April 1st.”

At least, the envoy had brought the matter directly to Marcos. Unlike Gen. Fabian Ver, then commanding general of the Presidential Security Command, who only mentioned Chongkhadikij’s profile of the president in an April 11 letter to Marcos. Of the four pages (13, 14, 15, 16) of the Bangkok Post that Ver had attached to his letter, none had Coffey’s piece which was on page 20.

Was Ver, ever the loyal and solicitous Marcos henchman, trying to shield the president from Coffey’s dark humor? But Ver was neck-deep in the whole Marcos-Beams affair, arranging the lovers’ trysts.

Figure 2. Amb. Manuel Yan’s June 14, 1973 letter to Pres. Ferdinand Marcos bearing Gerry Coffey’s apology to the First Couple.

Yan’s June 14 letter, carried the desired ending to the Coffey story: an apology. Three months after publication of her article, Marcos’s diplomatic agents got the apology from Coffey.

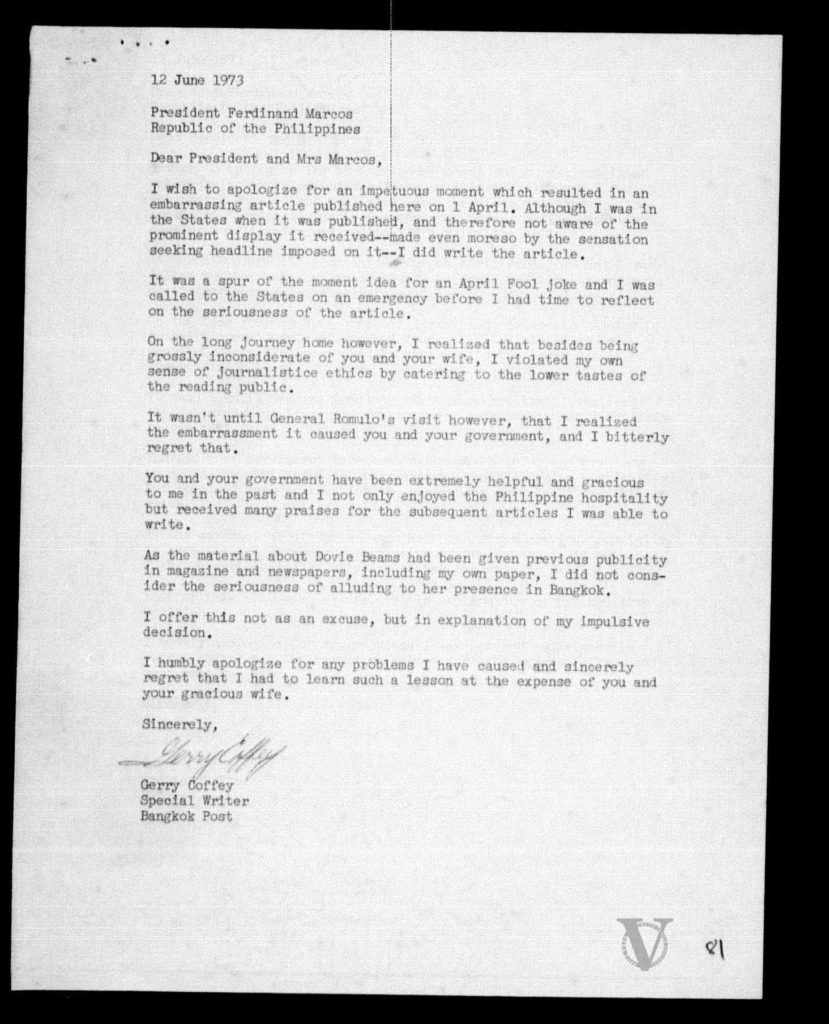

“It was a spur of the moment idea for an April Fool joke and I was called to the States on an emergency before I had the time to reflect on the seriousness of the article,” Coffey explained in a June 12, 1973 letter to Ferdinand and Imelda.

“On the long journey home,” she continued, “I realized that besides being grossly inconsiderate of you and your wife, I violated my own sense of journalistice [sic] ethics by catering to the lower tastes of the reading public.”

“It wasn’t until General (Carlos) Romulo’s visit however, that I realized the embarrassment it caused you and your government, and I bitterly regret that,” Coffey finally wrote.

The visit she was referring to, based on the Foreign Service Institute publication Philippine Diplomacy: Chronology and Documents, 1972-1981, is likely the one that took place on April 13-21, 1973. Romulo, as foreign affairs secretary, attended the Sixth ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting in Pattaya, southeast of Bangkok.

There is no indication that Coffey wanted her apology to be published or for the joke to be spelled out for everyone, and no one in Marcos’s propaganda corps probably felt the need to bring up Beams again in the state-controlled press in the Philippines.

In her apology, Coffey stated, “As the material about Dovie Beams had been given previous publicity in magazine and newspapers, including my own paper [referring either to the Post or the now defunct Bangkok World, where she served as “women’s editor”], I did not consider the seriousness of alluding to her presence in Bangkok.”

The real Dovie Beams affair

By the time Marcos received Coffey’s letter, he had been “dealing with” Beams for a little over four years.

Well before the actress became a household name in the Philippines, Marcos’ penchant for women was already an open secret. As has been detailed before, Imelda wasn’t even the first “Mrs. Marcos”; the story of Carmen Ortega was already well-disseminated by 1969, thanks to Carmen Navarro Pedrosa’s The Untold Story of Imelda Marcos.

That same year, news of an alleged affair between Marcos and the wife of a United States Navy made the rounds among American diplomats, as reported by Jack Anderson in an article carried by newspapers such as the Indiana Gazette and the Great Bend Tribune in September.

Former U.S. Embassy Consul General Lewis Gleeck Jr. wrote in his book President Marcos and the Philippine Political Culture that it was not actually a naval officer’s wife. He said the “actual offended party [was] bent on making a public scandal,” but was dissuaded after getting a “stern lecture” on the dignity of the Office of the President by Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor.

“There is no doubt that Ferdinand, to put it vulgarly, screwed around,” James Hamilton-Paterson wrote in America’s Boy, adding that “there is reason for thinking that mere sexual encounters were not by any means the only thing he wanted, and it was the emotional seriousness of his unexpected relationship with Dovie Beams that caused all the problems.”

Between late 1968 and early 1969, Beams was cast as one of the leads in the film Maharlika, an American-Philippine co-production based on Marcos’s war years. According to Beams, as relayed by Hermie Rotea in his book Marcos’ Lovey Dovie, her travel to the Philippines was arranged by Marcos crony Potenciano “Nanoy” Ilusorio as the movie was filmed on location.

But Maharlika was never publicly screened anywhere save in Guam, where an unfinished version had a brief theatrical run in August 1970. A bootleg version appeared in the 1980s, retitled Guerrilla Strike Force.

It is unclear when the decision to shelve the film was made. Letters purportedly from Beams, dated October 29 and November 6, 1970 and currently in the custody of the Presidential Commission on Good Government, state that it was she who asked the Philippine production company to stop the film from being shown as it was still unfinished and she had not been fully compensated. After Maharlika’s screenings in Guam, Beams was described in American newspapers, including The Los Angeles Times, as the head of the Manila-based production firm Creativity Films, and was casting for a film titled Aftermath.

It was on November 11, 1970 that Beams rose to infamy. In a press conference at the Bayview hotel in Manila, she divulged the details of her torrid affair with Marcos and played a snippet of one of their secretly recorded sexual encounters.

According to scholar Caroline Hau, “[the] airing of Marcos’s bedroom antics—from the most intimate of conversations to the most intimate of acts—exposed him to public hilarity and humiliation, effectively chipping away at his own carefully crafted public persona as devoted husband and heroic statesman.”

Washington naturally was concerned. Telegrams were sent from the U.S. embassy in Manila, then headed by Ambassador Henry Byroade, on Beams’s disclosures and movements. Shortly after her press conference, the actress was escorted out of the country by American consul Lawrence Harris, with immigration associate commissioner Victor Nituda, several other immigration officers, and press secretary Francisco Tatad.

Philippine officials made clear that Beams was not being deported; in a November 14, 1970 article titled “No Pressure, Miss Beams,” in Guam’s Pacific Daily News, the actress said she had been “assured by immigration authorities that she could come back anytime she wanted.”

At least that was what the Philippine News Service stressed.

There is no record of Beams ever returning to the Philippines. Her prospects of coming back were likely further dimmed after a failed assassination attempt in Hong Kong a few days after she left the Philippines. Former Hong Kong Standard editor Kevin Sinclair recalled witnessing a standoff between local police and “five killers with Philippine diplomatic passports” at the hotel where Beams was staying.

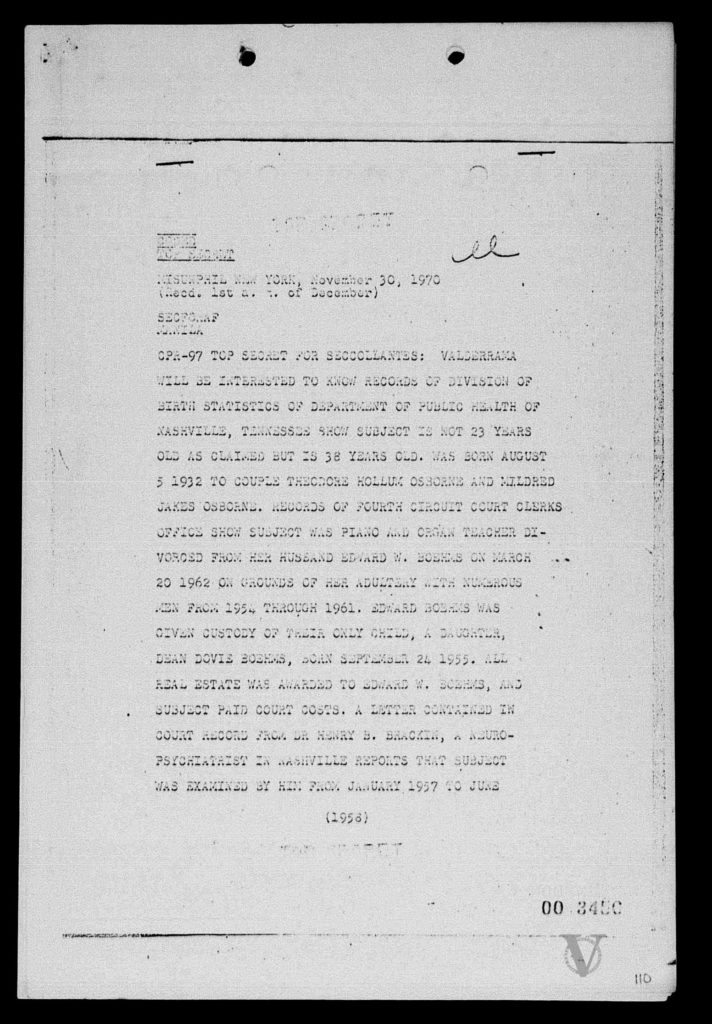

Seeing the impact of the Beams revelations on Marcos’s image, his regime’s diplomatic corps in the U.S. was put to work in an effort to dig up dirt on the private life of the American actress. In a cable sent from the Philippines Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York to acting foreign secretary Manuel Collantes dated November 30, 1970, Romulo relayed privileged information about Beams from birth statistics records of the Department of Public Health of Nashville, Tennessee (revealing that she was older than she claimed) and records of the Fourth Circuit Court Clerk’s Office detailing her divorce from her ex-husband Edward Boehms.

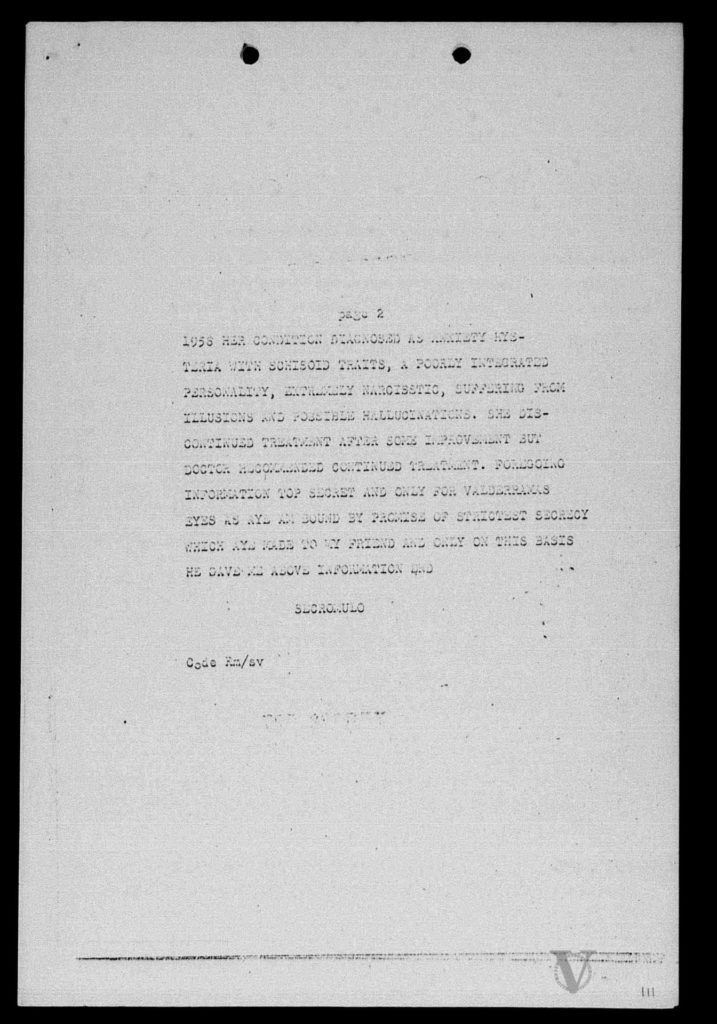

The divorce papers included a report from psychiatrist Dr. Henry B. Brackin, who diagnosed Beams with “anxiety hysteria with schisoid (sic) traits, a poorly integrated personality, extremely narcissistic, suffering from illusions and possible hallucinations.”

Figure 3. Foreign Affairs Sec. Carlos P. Romulo’s cable to Manuel Collantes, November 30, 1970.

Romulo emphasized that the information was “top secret” and only for the eyes of Nicasio Valderrama, then first secretary and press officer of the Philippines Permanent Mission to the UN. Still, the information in Romulo’s letter made national news.

In a December 10, 1970 diary entry, Marcos wrote that Roberto Benedicto, Juan Ponce Enrile, and Supreme Court justices Antonio Barredo and Claudio Teehankee “all agree that [their] idea of filing a case of blackmail or libel” against Beams was “not wise” and “recommend[ed] that we meet the Dovie Boehms attack with silence and not descend to her level.”

By January 1971, Marcos seemed to have weathered the crisis. According to a Memorandum of Conversation detailing a meeting of U.S. President Richard Nixon with Ambassador Byroade, and diplomat John H. Holdridge,

[Nixon] wanted to know how Marcos was getting along with respect to the Dovey Beams case. [Byroade] said that the case hadn’t really caused Marcos all that much difficulty, since Philippine mores were quite different from our own. The only criticism of Marcos appeared to be over the fact that he got caught out. Whatever he did, he shouldn’t have let Miss Beams make tapes of his liaison. According to [Byroade], Miss Beams was still trying to keep something of a hold over Marcos.

But a few months later, in a March 12, 1971 entry, Marcos wrote that he had directed Potenciano “Nanoy” Ilusorio to “push through the extortion case against Dovie Beams who is still intimidating everyone by false publications, this time in the Detroit Free Press.” In an article in that newspaper on February 28, 1971 with the headline “The Scary World of One Dovie Beams,” the actress said she turned down a $2 million bribe to stop talking about her affair with Marcos. An article in Government Report, a publication of the National Media Production Center, dated May 10, 1971 confirmed that a case against Beams for blackmail was “pending in the Pasig court of first instance.”

It is not known if the case was ever dropped.

Alongside the blackmail case, a character assassination project also took its course in print. As recalled in Hermie Rotea’s Lovey Dovie, the magazine Republic Weekly, a known Marcos publication, released a 10-part series on Beams entitled “The Real Story” which ran from February 26 to April 30, 1971.

Each story, accompanied by nude photographs of Beams, painted her as “an obscure Hollywood bit player who had come to Manila to extort money from President Marcos and from certain businessmen who claim to be close to the President.” A certain “A.E.,” the anonymous contributor who wrote the series, described the love affair as “a figment of Dovie’s imagination,” and detailed her alleged psychiatric diagnosis. Referencing the divorce proceedings earlier alluded to by Romulo, “A.E.” proceeded with a malicious description of Beams’s supposed past.

In 1971, Maharlika was shelved indefinitely on orders of the first lady. In a letter to Imelda dated November 10, 1980, producer Luis Nepomuceno stated that the first lady had entrusted to him “the responsibility of safeguarding the film [Maharlika] which we shelved from exhibition.”

Two years later, Beams said she would reveal details of her love affair with Marcos in a forthcoming book entitled Dovie Beams by Me. She made the announcement in a March 11, 1973 Parade magazine article that featured a picture of her with Marcos autographed by the president. Parade was distributed by hundreds of newspapers across the U.S.

But the tell-all book Beams kept saying she was writing was never released. Rotea’s Lovey Dovie was released in 1983 and is the only book-length treatment of the Dovie Beams affair. It includes information the author gathered from “marathon” interviews with Beams in Beverly Hills in 1973, transcripts of some of the recorded lovemaking sessions, and small unreadable reproductions of the Republic Weekly series where one can make out Beams’s “X-rated” photos.

There is no way of knowing if Marcos still cared about the issue from 1973 onward. There is no mention of the Dobbie-Coffey fiasco in Marcos’s diary entries between April and June 1973. However, various accounts — such as Pedrosa’s Imelda Romualdez Marcos: The Verdict and Beth Day Romulo’s Inside the Palace — claim that Imelda never forgot.

The other women

If their marriage had become more professional than romantic by the time Beams first made her disclosures, Ferdinand and Imelda didn’t show it. Instead, there were public displays of affection, lavish birthday and wedding anniversary celebrations complete with infrastructural “gifts,” and repeated allusions to him as Malakas and her as Maganda.

It was all a hoax, of course.

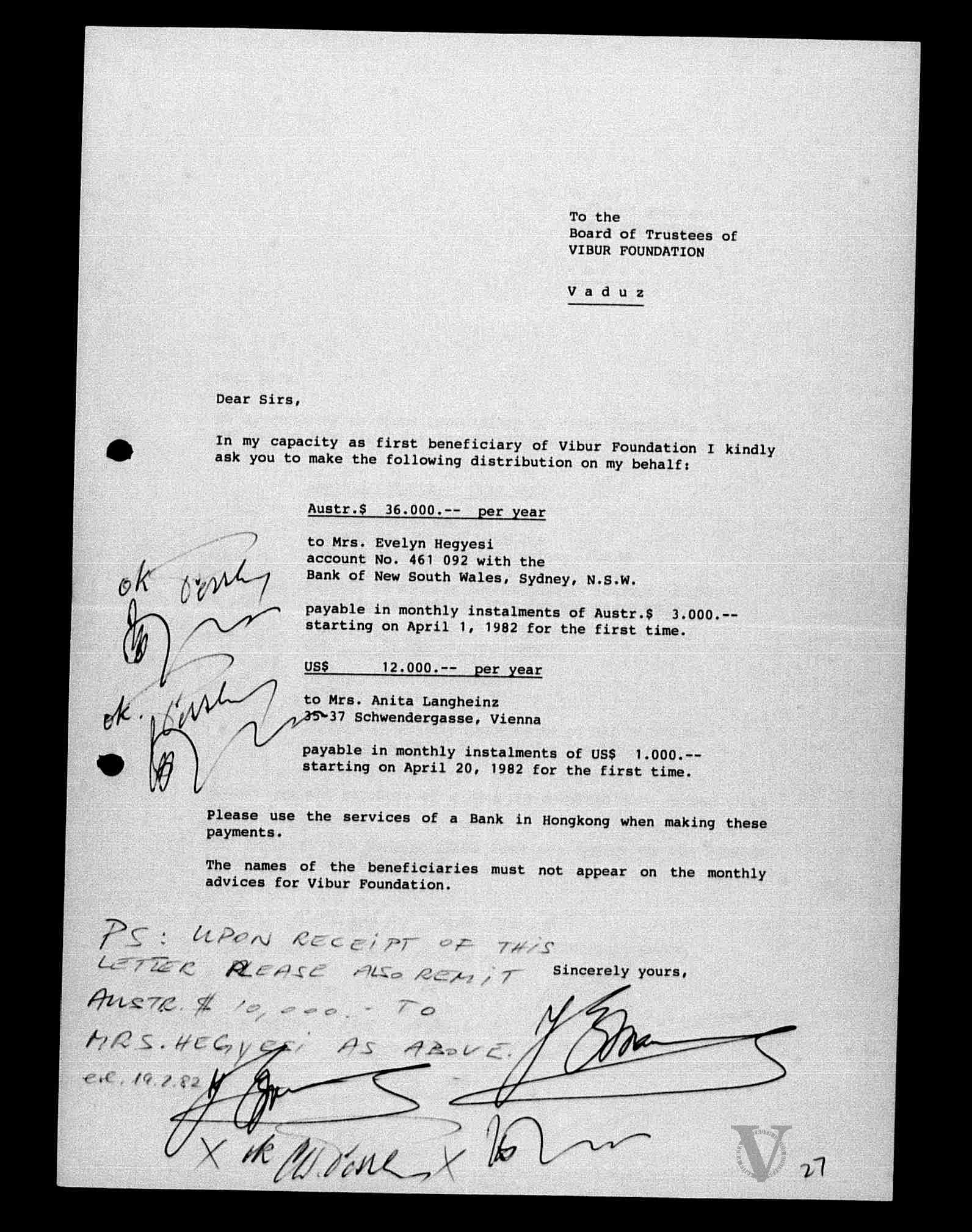

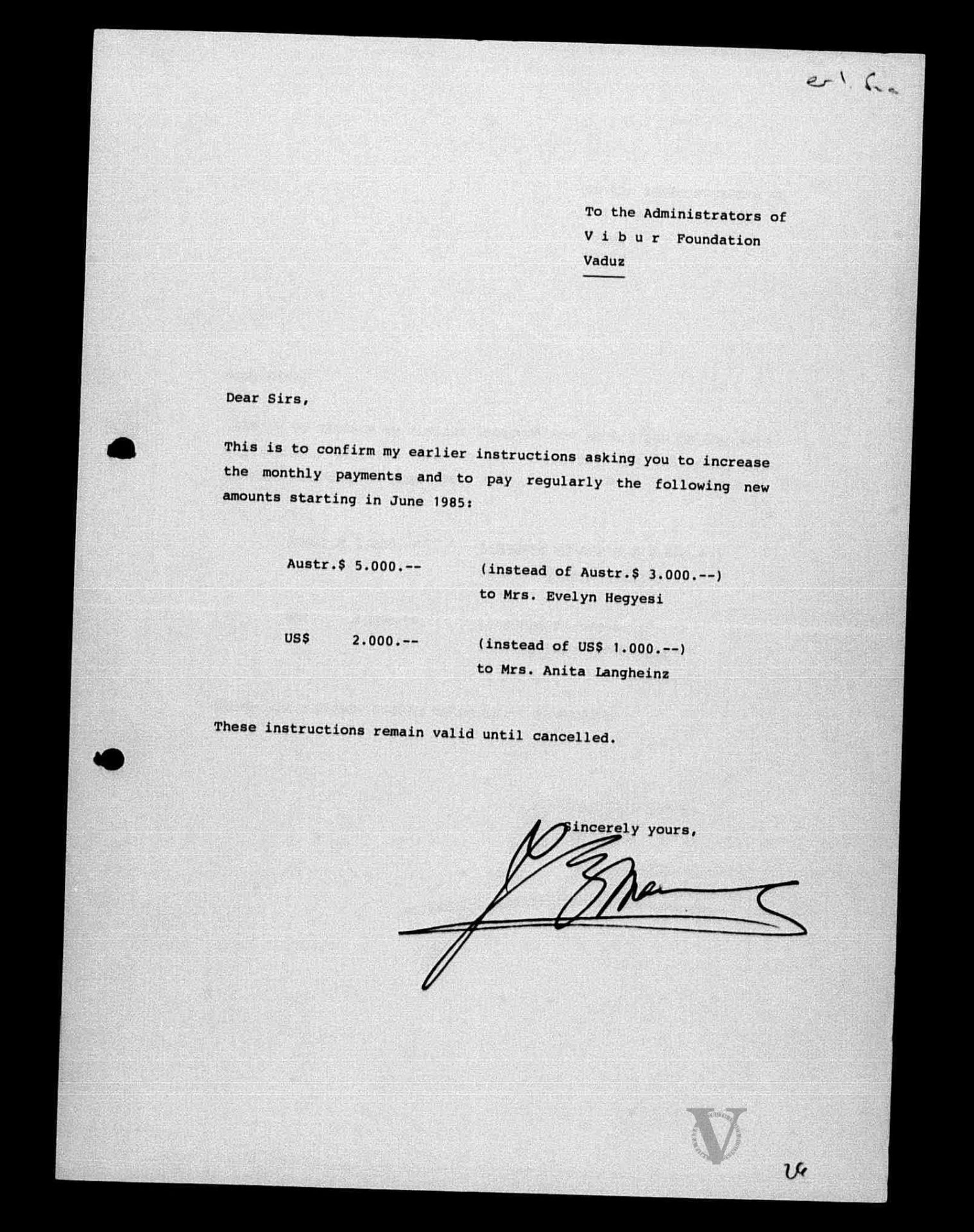

Documents on the transfer of ill-gotten funds from the Swiss bank accounts of the Marcoses to the Philippine treasury show that among the beneficiaries of the couple’s “foundations” were two women: Evelin Hegyesi in Sidney, Australia and Anita Langheinz in Vienna, Austria.

It remains unclear who Langheinz is, but Hegyesi, a model whose photos appeared in Playboy and Australian dailies and weeklies, is now best known as the mother of President Bongbong Marcos’s alleged half sister, Analisa Josefa (as in Josefa Marcos, the late dictator’s mother). Analisa was reportedly born in April 1971— five months after Beams left the Philippines and two years before Coffey’s article came out.

A February 1982 order from Marcos, in his “capacity as first beneficiary,” to the Board of Trustees of the Vibur Foundation, directed the “distribution” of Australian $3,000 a month to Hegyesi and U.S. $1,000 also monthly on his behalf.

Hegyesi’s deposits were to start on April 1, 1982, but the order was no April Fools’ joke.

In fact, it included a remittance of Australian $10,000 to Hegyesi “upon receipt of this letter.” Marcos amended his order in 1985 stating that beginning June of that year, Langheinz was to receive U.S. $2,000 per month and Hegyesi, Australian $5,000.

Coffey’s prank article stated that Dobbie Beams met Marcos through a “fast-rising former senator of the Philippines who allegedly lost favor with the First Lady because of his unlimited supply of young beautiful starlets who were placed at the beck and call of government officials.”

Clearly, as with all jokes, Coffey’s April Fool piece had a grain of truth in it —or better yet, an entire sackful mixed with crystalline crap.