Originally published by Vera Files on January 28, 2021.

Toting long firearms and with the media in tow, without any coordination with either the proper authorities of the University of the Philippines (UP) or barangay officials, the military trucks rolled inside UP Diliman to the Materials Recovery Facility in Pook Amorsolo and the gardens in Pook Village B and Pook Arboretum noontime of Jan. 20, 2021.

That was five days after Defense Secretary Delfin N. Lorenzana informed UP President Danilo Concepcion that he is terminating the 1989 agreement between UP and the Department of National Defense (DND) on military and police operations in the premier state university.

Members of the 7th Civil Relations Group of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), said they were visiting their urban farming project in UP Diliman.

Barangay UP Campus chairperson Zenaida P. Lectura, however, belied in a statement that the AFP has an urban farming project in UP Diliman. “The Sangguniang Barangay “maintains that our barangay projects does not involve AFP,” she said.

Lectura said Barangay UP Campus’s “Urban Garden Project” has been around “for a number of years now, even before this present administration.”

In July last year, the AFP did give Barangay UP Campus some seedlings for its project. The plants that grew out of those seedlings have long been harvested. Out of that token gesture, the AFP, as reported by Danilo J. Arceo, a council member of Barangay UP Campus, “went inside the garden and put up a marker indicating it was their project.”

Lectura said she is “appalled that Barangay UP Campus was used for whatever intention of the AFP to justify their presence within our barangay and for the issue on the abrogation of the UP-DND Accord of 1989.”

In his letter, Lorenzana said the agreement is “a hindrance in providing effective security, safety and welfare of the students, faculty, and employees of UP.”

Using the Anti-Terrorism Council’s (ATC) designation of the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) as a terrorist organization, Lorenzana alleges that “there is indeed an ongoing clandestine recruitment inside U.P. campuses nationwide for membership in the CPP/NPA and that the ‘Agreement’ is being used by the CPP/NPA recruiters and supporters as a shield or propaganda so that government law enforcers are barred from conducting operations against CPP/NPA.” The law that created the ATC is being questioned before the Supreme Court by 37 groups.

Lorenzana tried to reassure Concepcion that he will not be stationing troops within campuses and that his only intent is “to reach out to the youth and provide them with another perspective on our nation and society. We want them to see their Armed Forces and Police as protectors worthy of trust and not fear.”

ALMOST A THREAT

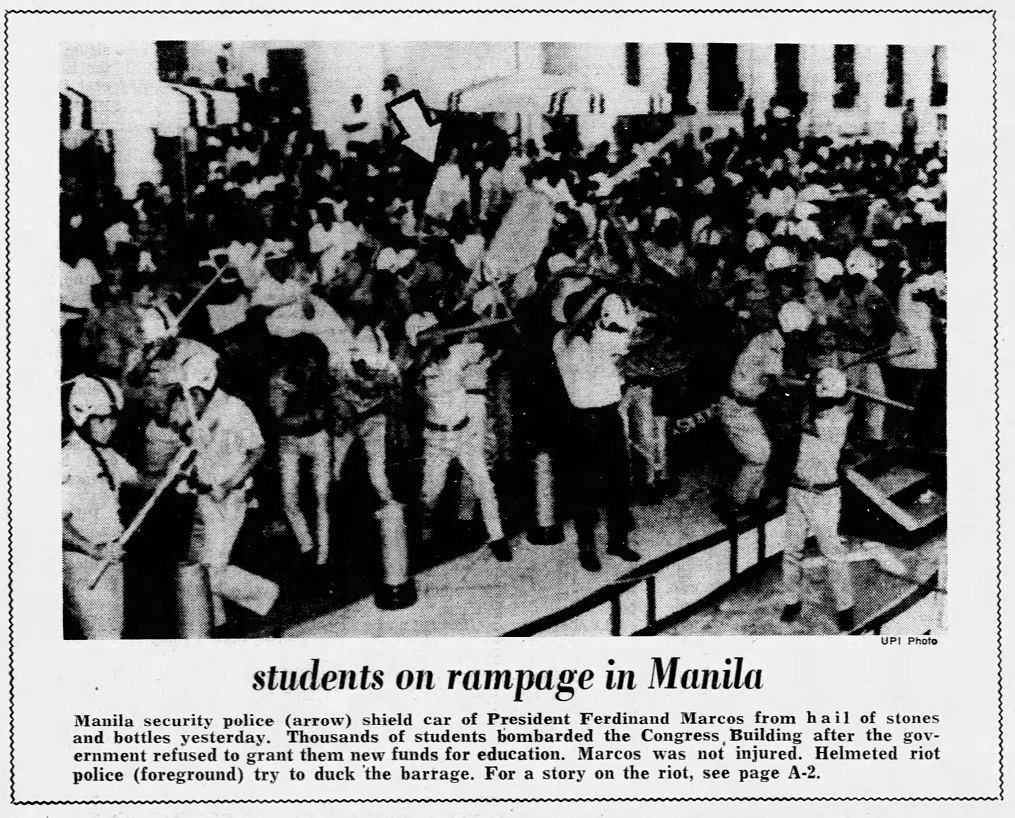

If the history of the presence and influence of the police and the military in UP is any indication, this is almost a threat. Fifty years ago, after the First Quarter Storm and the Diliman Commune, with the full force of the martial backing it up, the military and the police tried what Lorenzana wanted. Their intervention ranged from planting spies to rigging a university student council election and other psywar ops. Those efforts failed to rid UP of what the Marcos regime then considered as “radical” elements.

When former president Ferdinand Marcos assumed dictatorial powers with his declaration of martial law on Sept. 21, 1972 (made public only on Sept. 23 after the enemies of his regime were rounded up), the Philippine Collegian and the student council were banned.

“The campus was teeming with civilian agents,” Marites Sison and Yvonne Chua wrote in Armando Malay’s biography, A Guardian of Memory (2002). Malay was UP’s Dean of Student Affairs from 1970-1978. “Many more were arrested from UP … Some UP cadets were apparently used to identify wanted professors like [Petronilo Bn.] Daroy.”

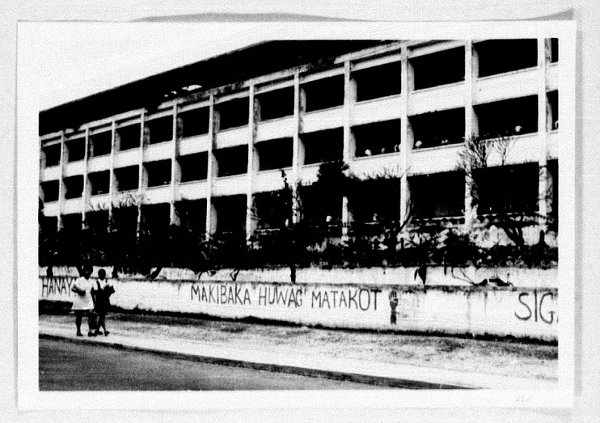

Activists’ slogan scrawled in front of the Palma Hall in the ’70s.

When the classes eventually resumed, military agents were sitting in on classes. According to a former UP professor cited by Sheena Chestnut Greitens in Dictators and their Secret Police (2016), during martial law, there were students that he “did not recognize, in plain clothes but with military haircut and demeanor, arriving to sit at the back of his classes.” Such acts were, in the words of Prof. Randy David, as quoted by Greitens, demonstrations of “the capacity of the government to monitor,” to “intimidate [one] more than to gather information.”

In Marcos’s diary entry on Sept.19, 1970, he said he has “finalized the instructions on intelligence work to continue. Directed Col. Fidel Ramos J-2 to assign men to all universities to collate information and infiltrate all organizations even on a ten year basis.”

The military’s boldness in making their presence known and felt in UP was rooted in a more extensive operation that had the full blessing and participation of Malacañang. And, needless to say, utilized taxpayers’ money.

RIGGING STUDENT COUNCIL ELECTIONS

In 1971, two parties were contesting the university student council elections in UP Diliman: Sandigang Makabansa (SM) and the more moderate/fraternity-backed Katipunan ng Malayang Pagkakaisa (KAMP/KMP). The standard bearer of SM was Reynaldo “Rey” Vea, an engineering student who had served as an editor of the Collegian. KMP’s candidate was Manuel “Manny” Ortega, a law student who was a member of Marcos’s fraternity, Upsilon Sigma Phi.

Both campaigned using black propaganda and acts of violence, including the use of weapons and explosives. Joseph Scalice, in his 2017 dissertation on the communist parties of the Philippines, mentioned a pillbox thrown during an election convocation during the tail end of the campaign. Ortega won the chairmanship by a little under 400 votes. KMP also won the vice chairmanship and half of the university council seats.

During the campaign, SM and allied groups repeatedly claimed that Ortega and KMP had the backing of Malacañang and the military, or at least were aligned with the government’s anti-communist drive. Scalice recounted the contents of pamphlets released by the “Secret Victor Corpus Movement” which claimed that the violent university convocation was part of “Operation Good Friday,” the “code-name of a highly confidential project being undertaken by Malacañang and the Armed Forces of the Philippines and being executed under the command of top psy-war expert and undersecretary of home defense, Jose Crisol,” which was aimed to “muzzle the militancy of UP as a preparatory step for the silencing of the national student movement.”

Former student leader Jaime Galvez Tan, in an interview quoted in the 1986 dissertation of UP professor Alexander Brillantes, stated that “goons were brought in (by the government)” during the 1971 convocation as agent provocateurs. In his blog, subtitled “Memoirs of an Anti-Martial Law Activist in the Philippines,” Roberto “Beto” Reyes wrote that when Ortega won, SM “quickly branded his victory as the result of ‘red scare’ tactics employed by the opposing party.”

Retrospective accounts, however, generally characterize Vea and SM’s defeat not as a product of government/military machinations, but as a tacit denunciation of the violence that happened during or sprung from the Diliman Commune. According to Scalice, “more than anything else, the UP students in 1971 were voting against the Diliman Commune and the conduct of the KM leadership of the Student Council.” Beto Reyes claimed in his blog that graffiti proclaiming “Long Live the Diliman Commune” and “Mabuhay ang mga Barikada,” among others, on the walls and blackboards of the College of Arts and Sciences building were among the reasons that the student voters, especially “uninitiated freshmen,” swung toward Ortega’s party.

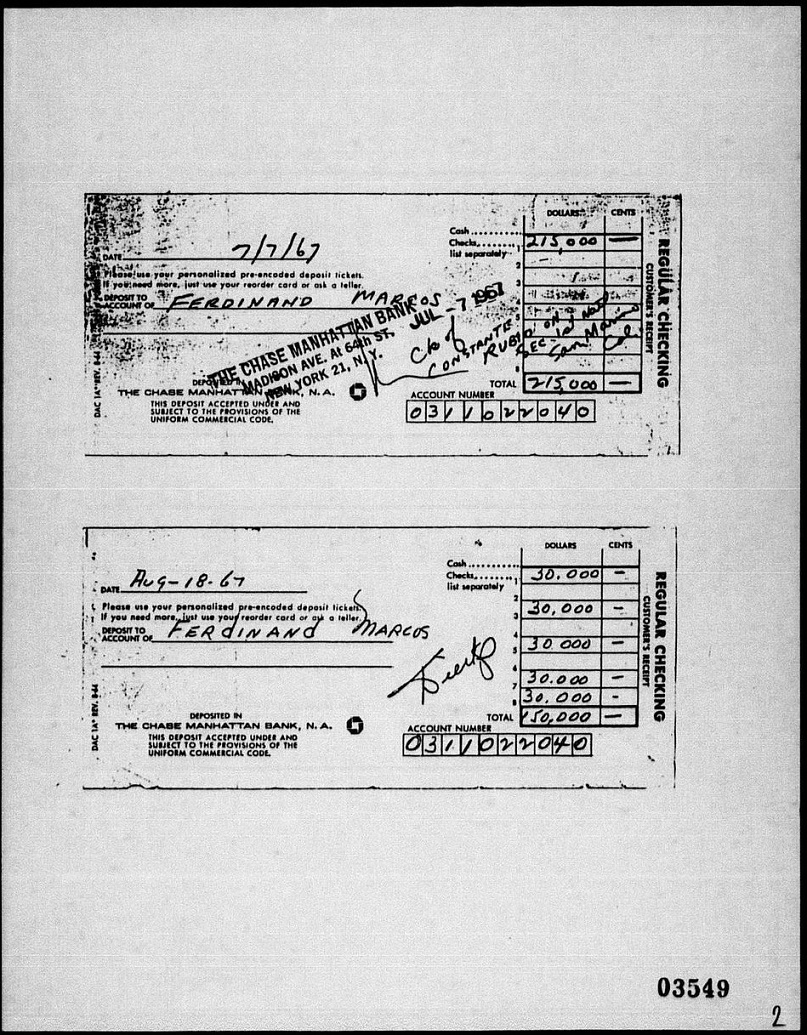

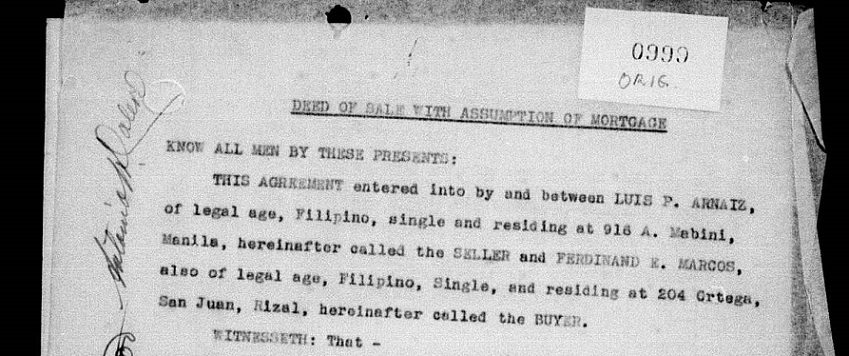

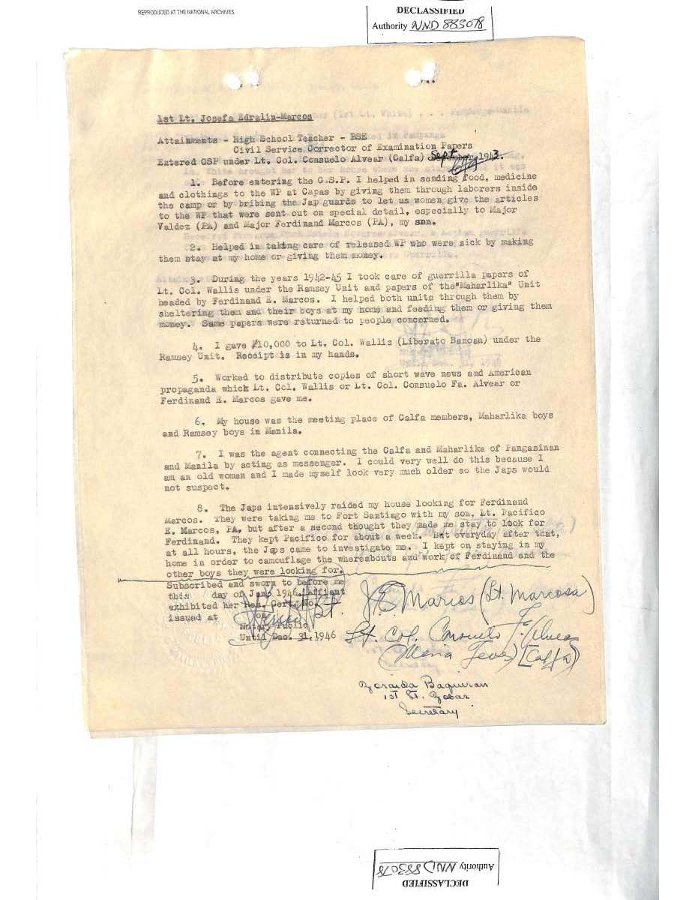

Among the papers left by Marcos in Malacañang after he was deposed were pieces of evidence that give credence to the accusations against Ortega and KMP. In a confidential letter to Marcos dated Aug.10, 1971, Crisol stated that to ensure Ortega and KMP’s win, a total of P17,600 -a considerable sum in 1971 – was spent by various agencies. According to Crisol, a total of P10,000 was given directly to Ortega by Malacañang (via then assistant executive secretary Roberto Reyes); P2,500 came from General Headquarters (GHQ)-AFP; P2,500 came from NICA [National Intelligence Coordinating Agency]; P1,000 came from the Office of Community Relations (OCR) GHQ (via “Col. Pecache”); and another P1,600 from NICA (via “Col. de la Fuente”).

Letter of Undersecretary of Home Defense, Jose Crisol to President Marcos

Crisol noted that the P2,500 each from GHQ AFP and NICA were “funneled through Lt. Col. [Benjamin R.] Vallejo in conducting the four broad psychological warfare activities that required expert, centralized and detailed implementation,” which included printing (counter)propaganda, “black propaganda vs SM organizations and personalities,” and “final persuasion of voters for friendly [organizations] and candidates.” Crisol further noted that “the key to victory was the positive commitment of the ROTC-based organizations in favor of the moderate coalition.”

Toward the conclusion of his letter, Crisol said: “Our student apparatus in Laguna succeeded in getting the Council Chairmanship in the Laguna Institute at Calamba.” That was, he added, “a forerunner of what we intend to do in contesting radical leadership in UP Los Baños by next year.”

Crisol’s “victory” lasted only until the next election. SM regained the council’s chairmanship in the 1972 elections (medical student Jaime Galvez Tan was SM’s standard bearer), but that council’s term was brief, since Marcos suspended all student councils and organizations upon imposing martial law throughout the Philippines in September 1972.

UNDERMINING CAMPUS PRESS

Not content with controlling the outcome of student council elections, military operatives also tried to undermine the free campus press.

Gravely concerned about the rhetoric of the student activists, Marcos’s military operatives placed UP’s student publications under close scrutiny. In the same memorandum written by Crisol to Marcos about the 1971 UP student council election, he outlined four psychological warfare activities jointly funded by Malacanang, the AFP GHQ, OCR, and NICA. One of these was the printing of the Free Collegian, a student tabloid designed to “counter the radical propaganda through the Collegian or other printed means.”

The Free Collegian cost these government agencies P1,500. A separate confidential report analyzing the “leftist radical defeat” in the campus election says that “[t]he FREE COLLEGIAN of the KAMP was disseminated at a right psychological moment. The SM had a panic reaction by forcibly confiscating the paper from student [sic] which served to alienate the radicals.”

The black propaganda rag also targeted university officials. As noted by Sison and Chua in Malay’s biography:

“Copies of The Free Collegian mysteriously appeared on the UP campus. One article, headlined “Malay Bankruptcy Assailed,” stated: “If you want to be the future vice president of the University of the Philippines, all you have to do is lick the boots of S.P. Lopez, submit to the imperial orders of the Student Council chairman, and kowtow to all the demands of the KM-SDK . . .” It described Malay as “old, decrepit, and senile.”

Because the military’s relatively small investment paid off quite handsomely in the UP campus election, in an assessment it was resolved to “[e]nhance [the] unity of direction of moderate student organizations” and to “intensify psyops in all schools affected by radical activism.”

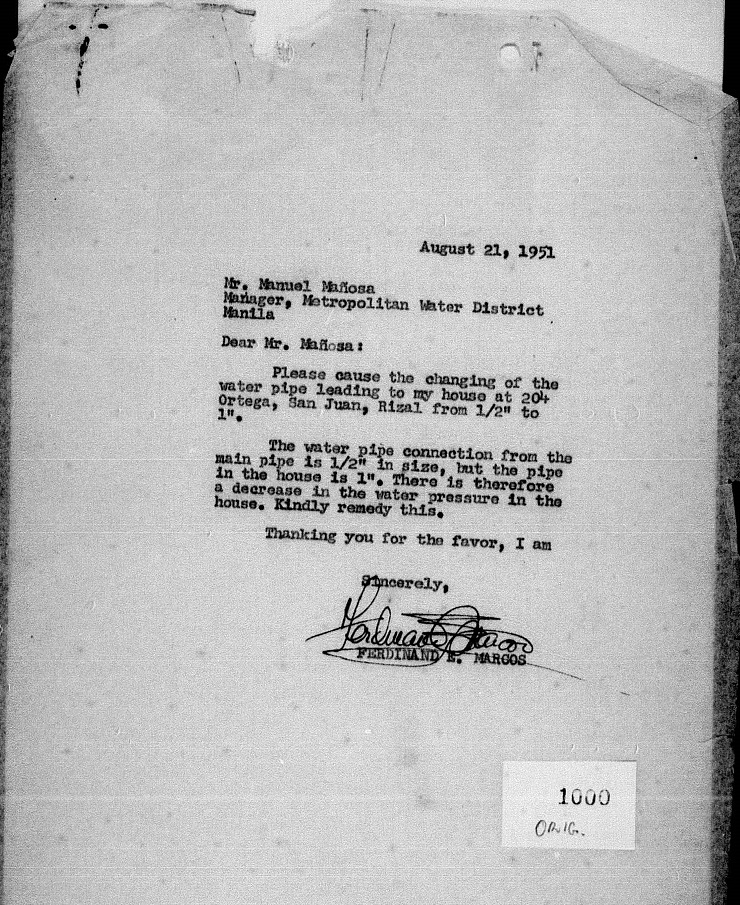

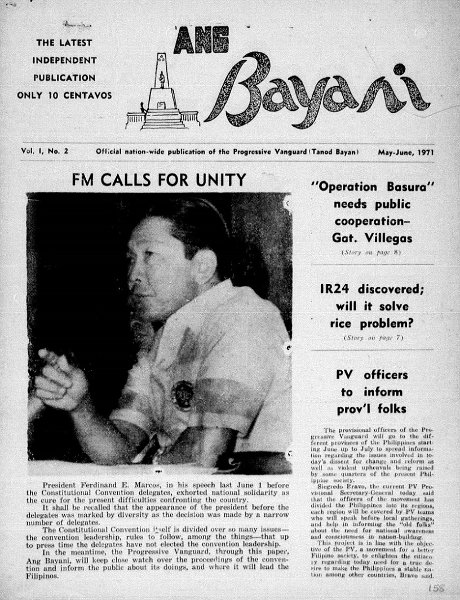

With the firm belief in the effectiveness of this sort of psychological ops, the minister of Public Information Francisco Tatad gave Marcos a copy of another student tabloid entitled Ang Bayani: Official nation-wide publication of the Progressive Vanguard (Tanod Bayan). The title seems to be a play on Ang Bayan, the official organ of the CPP. In a memorandum dated Aug. 9, 1971, Tatad wrote Marcos: “[t]he attached copy is a project of our university boys. They plan to use this extensively during the campaign, particularly during the school mock elections. Can we extend to them some modest support? It will be worth it.” The phrase “modest support” was underlined and annotated with the amount “P2,000.”

Frontpage of Malacañang -funded tabloid Ang Bayani, a play on the CPP-NPA’s official news organ, Ang Bayan.

Ang Bayani, which started circulating as early as March 1971, visibly lauded government programs and vilified student protests. The writers of the tabloid expressed tacit support for the ongoing Constitutional Convention and to the effort of the state’s security forces to suppress dissent. They featured a letter to the editor from the president of the Kapisanan ng Malayang Pilipino (KMP), congratulating Philippine Constabulary chief Gen. Eduardo Garcia “for his decision to enforce laws on subversion and sedition.” The letter continued: “Lately, we have observed that our country has assumed an anarchic atmosphere as a result of the indiscriminate holding of rallies and demonstrations and the consequent use of abusive and venomenous [sic] language by so-called self-styled reformers, who prefer rabble-rousing techniques and destructive criticisms rather than undertake positive actions.”

Five years later, psyops turned visceral with the actual arrest of UP campus journalists and activists.

For writing an editorial that was highly critical of the Marcos regime, and refusing to heed a warning of then minister of Defense Juan Ponce Enrile to tone down their anti-government content, Philippine Collegian editor-in-chief Abraham “Ditto” Sarmiento was arrested at his house in January 1976. Before his arrest, on Jan. 23, 1976, news that other students, including the Collegian’s managing editor, had been detained resulted in a swiftly organized protest march in the Diliman campus. According to a declassified US Department of State cable dated Jan. 28, 1976, the demonstrators numbered between 500 and 1,000. The protest was broken up by campus police. Ten were arrested in UP, but were released on the same day.

In another declassified cable, dated Feb. 2, 1976, US ambassador to the Philippines William H. Sullivan stated that “about 17 or 18 persons from the UP community have been picked up by [the] military over [the] past two weeks and are still being detained,” including Sarmiento. According to Sullivan, during a university council meeting on January 31, then UP president Onofre D. Corpuz, Marcos’s former education secretary, stated his view that “students engaged in protest movements must be prepared to bear consequences of their actions,” and that the “university could do little officially to help the students.” Corpuz nevertheless said that “he had discussed [the] matter privately with government officials” and that believed Sarmiento would be released in a week’s time.

Sarmiento was released more than seven months after his arrest. He died of a heart attack in November 1977, believed to have been a consequence of his poor health that deteriorated while in detention.

Corpuz’s callousness can be contrasted with the clear interest in the welfare of student prisoners taken by his immediate predecessor, SP Lopez. According to Oscar Evangelista, in his history of the Lopez presidency in University of the Philippines: The First 75 Years (1985), Lopez “went out of his way to protect the students, even visiting the city jails to look after those arrested by the police for participating in riotous demonstrations.”

EXPANDING CONTROL

Then the drive for control turned institutional.

“PCAS Infiltrates the [UP] System,” wrote Evangelista. The Philippine Center for Advanced Studies (PCAS), as candidly admitted by Jose Almonte in his memoir, Endless Journey (2015), was a think tank for Marcos.

PCAS was an autonomous UP unit that came into existence in 1973 via Presidential Decree 342. Its finances, as provided for by Marcos, “shall not be subject to the procurement requirement and restrictions imposed by existing law.”

For PCAS to have its own building in UP Diliman, Alejandro Melchor Jr., then Marcos’s executive secretary, as told by Almonte in his memoir, “saw an item for a hospital or school somewhere. He cancelled the budget for that hospital or school and transferred the funds to the PCAS for the construction of a building.” That building still stands on campus today, the Romulo Hall.

For Evangelista, “the creation of the PCAS established an empire within an empire…particularly vexing to the UP community was the fact that it was imposed from above without consultation or agreement.”

Though said to have been given P20 million by Marcos, PCAS ended up siphoning off funds from UP. The finances of the then existing Asian Center was transferred to PCAS. And UP, starting 1974, had to give PCAS P1.5 million from its own budget.

PCAS formulated policies and provided some of the ideological underpinnings for the continued imposition of martial law. Or as Marcos puts it in PD 342, its members were to “address themselves to the examination of issues of central concern to the government, such as problems of national integration, social technological and cultural change, social effects of national policy, international developments and their impact on our national life, as well as security and strategic problems.”

Almonte, then a colonel, claims to be the main Marcos man who ran it. “I was the vice chancellor and at the same time, dean of the Institute for Strategic Studies. Ruben [Santos Cuyugan, PCAS chancellor] also designated me professor of social engineering . . . I get a good laugh whenever I remember this because nowhere in UP or perhaps other universities in the region was there such a discipline. In the military, there was no such academic field.” What Almonte was, in fact, laughing at was how PCAS trounced the established meritocracy in UP.

But in the end, PCAS’s own activities made it suspicious even to Marcos. One particular program stood out, as pointed out by S. Lily Mendoza in Between the Homeland and the Diaspora (2002):

“Another effect of the travel ban was that government officials and employees (both military and civilian) who did manage to secure special permission to travel abroad were now mandated to first undergo training with the [PCAS], a semi-autonomous unit within the University of the Philippines System commissioned (commandeered?) by the Office of the (Philippine) President to service its policy research and strategic needs . . . . Rumor has it that it was from the threat of its pre-departure seminars “placing brains in men with guns” that finally did it in, referring to what was noted as the potentially subversive effect of the program’s nationalist orientation on military officers undergoing training.”

On Aug. 9, 1979, Marcos ended PCAS through Letter of Instruction 908 in favor of his other creation, the President’s Center for Special Studies. Almonte recalled that “Marcos abolished the PCAS in 1979 when he sensed that we no longer conformed to his idea of strengthening the nation.”

From saving UP students from the clutches of communism to “strengthening the nation,” stories abound of other cases of surveillance, interference, and even violent intrusion in UP by elements of the Armed Forces throughout the Marcos dictatorship. In addition, among other draconian measures implemented during Marcos’s rule, an anti-subversion law was, in effect, making mere membership in the CPP illegal. Finally, by November 1977, both CPP founder Jose Maria Sison and NPA founder Bernabe Buscayno had were captured by state forces. With such tools, techniques, and developments — and the absence of an enforceable explicit agreement like the 1989 UP-DND Accord — was the CPP-NPA successfully suppressed?

BEST CPP-NPA RECRUITER

It has become a cliché to state that the best recruiter of the CPP-NPA during the Marcos regime was Marcos. Indeed, in Proclamation 1081, or the martial law proclamation, Marcos stated that by July 31, 1972, the NPA had a total strength of 7,900, of which only 1,028 were regulars. In the last book authored by Marcos, A Trilogy on the Transformation of Philippine Society, Marcos stated that by 1985, his final full year in office, the NPA had 16,000 regulars.

In his 2006 thesis, “An Analysis of the Communist Counterinsurgency in the Philippines,” submitted to the US Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Antonio Parlade Jr. — now Lt. Gen., head of the Southern Luzon Military Command, and spokesperson of the NTF-ELCAC (National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict) — gave the following description of how the poor, particularly the peasantry, were driven to join the NPA during what he called Marcos’s “reign of terror”:

“[Marcos] had to expand the military organization and patronize the generals to buy their loyalty. Further dampening their morale was the lack of combat equipment and essential organizational requirements to perform their job. Corruption became rampant in the ranks and improving the state of discipline of the troops was hardly a priority. As a result, human rights abuses by the troops became rampant, which further alienated the disadvantaged poor who were caught in the fight between the NPA and government forces. As life being experienced by peasants in the hills was getting harder, they saw the communist party as an option to realize their simple dreams. Uneducated as they were, they became easy prey to the propaganda campaign of the insurgents … When they became suspects for harboring the insurgents in their homes and were beaten by an abusive constabulary on patrol, it was only a matter of time for them to run to the hills and join the NPA.”

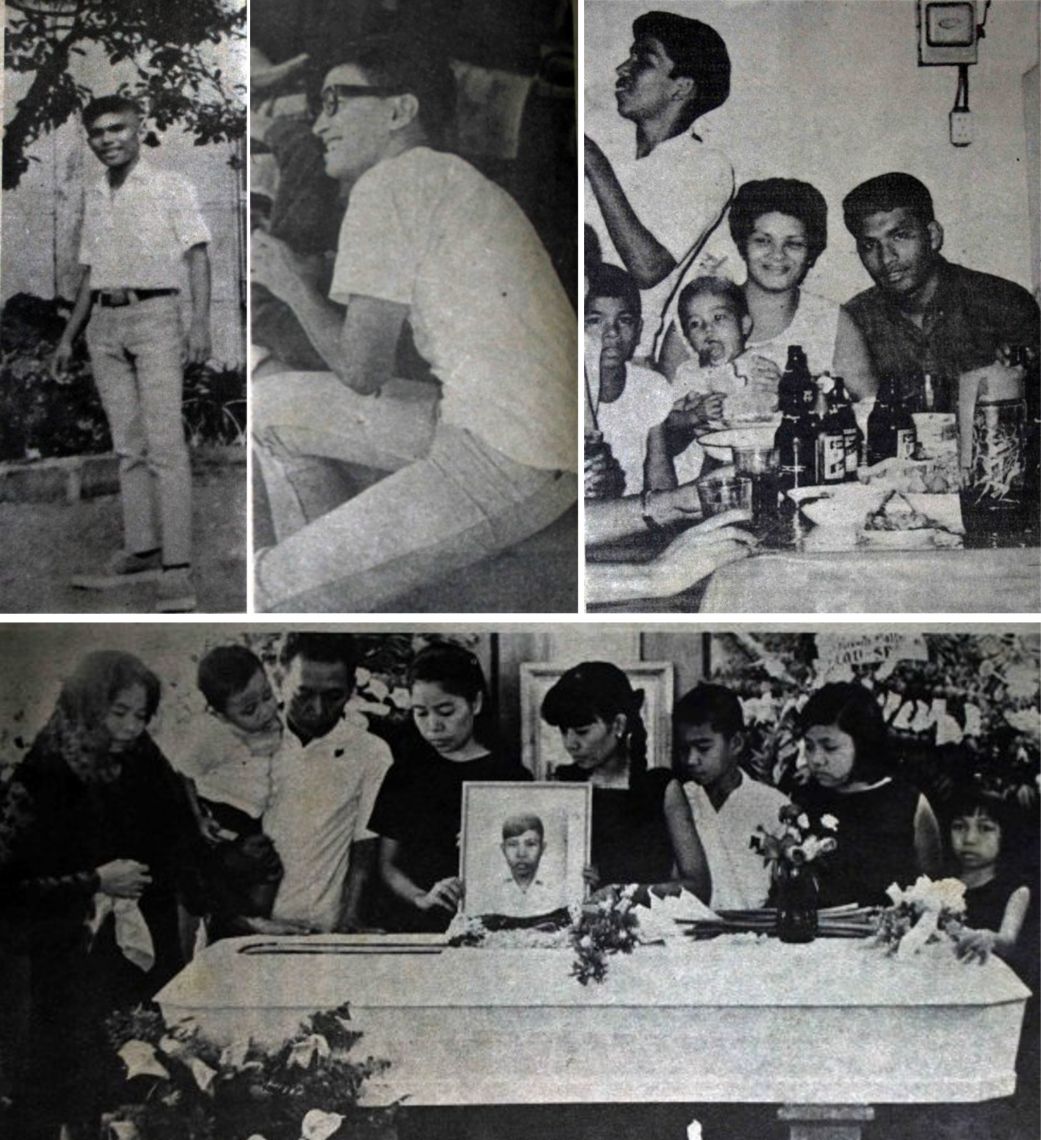

The claim that people were driven to join the NPA because of military abuse recalls the claims about why UP graduate student and activist Maria Lorena Barros went underground. Barros was among those charged with subversion in the wake of the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus following the Plaza Miranda bombing in 1971. From teaching and studying in the university, she went to the countryside, where she joined the armed struggle. After being captured in 1973, she was able to escape from incarceration a year later. She was killed during an encounter with the military in 1976 at the age of 28.

Today, Parlade and the rest of the NTF-ELCAC are insistent that CPP-NPA recruitment hubs can be found in UP and dozens of other institutions of higher learning, though it seems that he requires further information of such alleged recruitment. “Mas mapag-aaralan ang nangyayaring recruitment ng CPP-NPA sa UP matapos maibasura ang UP-DND accord (The CPP-NPA recruitment in UP can be studied further after dispensing with the UP-DND accord),” he was quoted as saying in a recent interview.

The NTF-ELCAC and Lorenzana are insistent that they are only looking out for the children. In the propaganda materials they release, they frequently include Barros, stating that she was one of the youths who joined the NPA because of deceptive recruitment practices, resulting in her death. Many online supporters of the NTF and Lorenzana have taken to stating that UP is either complicit in the alleged recruitment, or has been very negligent in exercising substitute parental authority over their students.

But history tells us that the parental metaphor can apply both ways. The AFP’s obsession with UP reminds one of a doddering, whiny, and abusive father who, though hard up to provide for his family, is often under the influence of alcohol and other drugs. To hide his impotence in securing his family a decent future, he just shuts them up, beats them up, and locks them up.