Originally published by Vera Files on February 22, 2022.

At 9:05 in the evening of February 25, 1986, as the multitude of Filipinos in revolt closed in on Malacañang, the Marcoses scurried out of the palace with their 22 crates of loot on board four helicopters from the United States embassy. It was believed that the deposed dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos had taken everyone dear to him and everything of immense value into exile.

He did not. Marcos abandoned his own mother.

“It wasn’t until a month later,” Nick Joaquin wrote in The Quartet of the Tiger Moon: Scenes from the People-Power Apocalypse, “that Doña Josefa was located at the Philippine Heart Center (PHC) in Quezon City, a patient there, it turned out, for the last eight years, running up bills amounting already to over a million pesos when her son fled the country, his mother’s hospital bills still unpaid. President Cory Aquino has announced that her office will pay those bills.”

Then PHC director Dr. Esperanza Cabral placed the bill at $57,333, about P7 million today. Josefa was later transferred to the Veterans Memorial Medical Center, where she died on May 4, 1988 at age 95.

This seems to be an unlikely parting for mother and son who used to be thick as thieves. Ferdinand is known to have cherished his mother, a high school teacher in Manila before the Second World War, as he found roles for her in consolidating his financial and political powers.

After the 1986 EDSA revolt, as Josefa languished in the government hospital, the public would learn more of the part she played in her son’s kleptocratic regime.

On June 6, 1966, in a ceremony at the then Independence (now Quirino) Grandstand, Ferdinand awarded his own mother, and 23 others, with a Presidential Merit Medal for campaigning for women’s right to vote which was won in 1937. Josefa’s role in the Philippine suffrage movement, however, is unclear.

Making suspect claims in a grand manner seemed to be a practice both mother and son indulged in. While Ferdinand’s exaggerated and criminal claims about his supposed heroism in World War II are now well documented, Josefa’s efforts in the conflict are not so well known.

Ferdinand’s war time ignominy are found in File No. 60, “Ang Mga Maharlika Grla Unit” and File No. 140, “Allas Intelligence Unit” from Record Group (RG) 47 of the Philippine Archives Collection. Physical copies of these documents may be viewed at the US National Archives in Washington and are freely accessible via the Philippine Archives Collection website of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office.

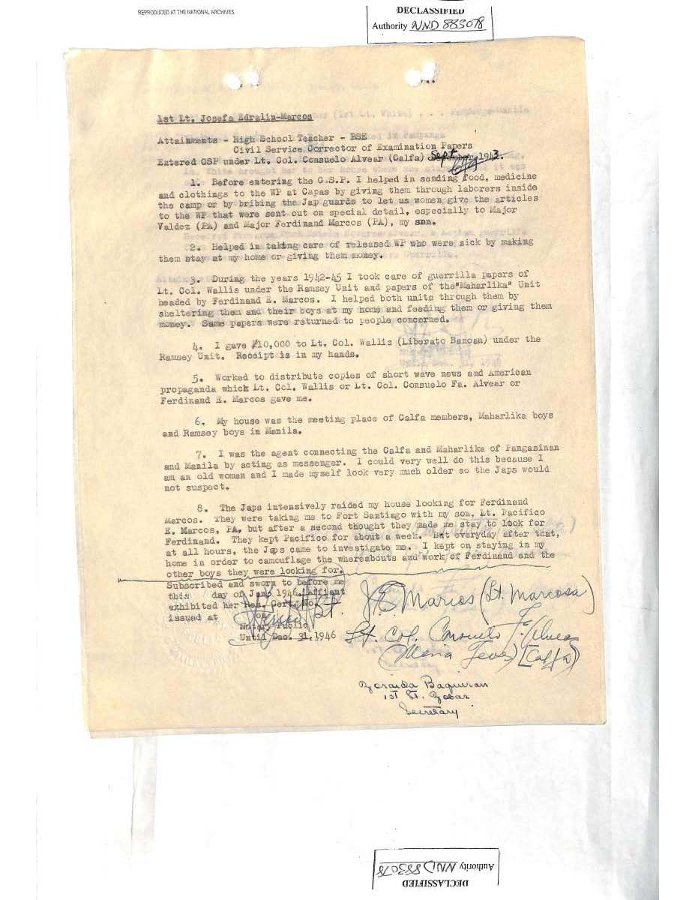

Josefa’s record is in File No. 253, “Guerrilla Special of the President (GSP)”

ANOTHER FAKE GUERRILLA IN THE FAMILY

Purportedly led by Consuelo Fa. Alvear, also known as “Maria Teves,” a teacher who claimed the rank of Lt. Col., the “GSP” counted among its roster “1st Lt.” Josefa E. Marcos. Both Alvear and Josefa graduated with degrees in education from the University of the Philippines in 1935.

GSP’s members were supposedly mostly women. Based on a profile of herself that Alvear included in her submissions, the “GSP” acronym also stood for another group to which she belonged, the Girl Scouts of the Philippines. Another name for GSP was Calfa, derived from Alvear’s name.

But Alvear made claims about activities unsupported by evidence. She stated that she joined a national oratorical competition where she placed second and that she attended Japanese language classes at the Nippongo Senmon Gakko to gather intelligence and was elected secretary of the student council in March 1944.

In a letter to Alvear dated February 26, 1947, Captain R.E. Cantrell wrote that GSP was “not favorably considered for recognition as an element of the Philippine Army” for lack of evidence that the unit existed as a sustained, structured, and cohesive group. Assessors also noted that “the number of officers, commissioned and non-commissioned, was excessive and not reasonably proportionate to the (U.S.) Army or to pre-war Philippine Army tables of organization.”

Indeed, the submitted GSP rosters listed over 60 persons with ranks ranging from 3rd Lt. to Lt. Col., although the unit only had 200 supposed members. Cantrell’s letter noted that many of these purported members were civilians, with some only claiming to have contributed money or supplies to the war effort. Their affidavits showed that some highlighted the roles of their relatives in the resistance effort. Josefa Marcos was one such “soldier.”

Josefa was not, based on a signed affidavit included in Alvear’s submissions, a gun-toting commando. She certainly was not, as implied by Ferdinand and his allies, a veritable one-person army. Josefa herself stated that before joining the GSP, she “helped in sending food, medicine and clothes to the WP [war prisoners] at Capas [Tarlac] by giving them through laborers inside the camp or by bribing the Jap guards to let us women give the articles to the WP that were sent out on special detail, especially to Major [Simeon] Valdez [her husband’s cousin] and Major Ferdinand Marcos…my son.”

Ferdinand was not a major when he was in Capas. He was a lieutenant.

She then claimed that she took care of released WPs at her home or gave them money, specifically mentioning giving P10,000 to Liberato Bonoan. Josefa described Bonoan as a member of the Ramsey Unit, or the East Central Luzon Guerrilla Area. Marcos’s mother further claimed that she distributed intelligence, served as a messenger between Calfa and Maharlika, and “took care” of Ramsey and Maharlika papers, returning them “to the people concerned.”

Josefa stated that her house on 1555 Calixto Dyco Street in Paco, Manila was “the meeting place of Calfa members, Maharlika boys and Ramsey boys in Manila.” That role apparently ended when the place was “intensively raided” by the Japanese who were supposedly looking for Ferdinand.

According to Josefa, both she and her younger son, Pacifico, were going to be sent to Fort Santiago, but she was allowed to stay home “to look for Ferdinand.” When Pacifico was released a week later, “at all hours, the Japs came to investigate [her; she] kept on staying in [her] home in order to camouflage the whereabouts and work of Ferdinand and the other boys they were looking for.”

By most accounts — generally by those who wrote favorably about Marcos’s wartime heroism — Pacifico’s arrest and release happened in August 1944.

Josefa executed her affidavit in January 1946, the same date as many of the other affidavits in Alvear’s submission. That was about five months after Ferdinand first filed the necessary paperwork to have Ang Mga Maharlika recognized by the U.S. Army. Ferdinand’s unit was not favorably considered (NFC) by the U.S. Army in June 1947, four months after GSP was also “NFC’d.” Ferdinand appealed, but the stories of Ang Mga Maharlika being a significant guerilla force was affirmed to be completely fake by the U.S. Army in March 1948.

Some claims in Josefa’s affidavit and Ferdinand’s documents do not add up. One document with the title “Ang Mga Maharlika: Its History in Brief” was submitted to U.S. Army assessors in December 1945. The most glaring deficiency in Ferdinand’s tales of Maharlika’s exploits and the other documents is the absence of any mention of GSP, Alvear, or his mother’s role in the war effort. The “History in Brief” contained a section called “Liaison with Other Guerrilla Groups.” That too had no reference to Calfa or Alvear.

Ferdinand mentioned many other relatives — Pacifico, a number of uncles, and even a barely disguised reference to his father, Mariano — but never Josefa. When Ferdinand talked about the time Pacifico’s room “was raided by two truckloads of Kempei Tai,” he remarkably failed to note that his mother was also there.

Although the former dictator referred to the Marcos home in Paco, he never claimed that it was a meeting place for guerrillas. References to his “quarters” in the “History in Brief” presumably refer to where he slept in that house. According to Ferdinand’s biography For Every Tear a Victory, written by American Hartzell Spence, the Marcos brothers shared a room where, Liberato Bonoan “used to hide out.” Marcos further stated in a document submitted to the U.S. that papers of the Maharlika “were buried in the lot” where their house stood. If this were correct, one wonders why the papers were not discovered when “Japs intensively raided” the property, as per Josefa’s narration, or when they visited her “everyday…at all hours.”

This claim of frequent visits also contradicts a story in Spence’s biography and 77 Days in Eastern Pangasinan, published in 1981 by the Office of Media Affairs, under the Headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary Historical Committee. Both these books state that Ferdinand returned home, after spending some time recuperating and hiding out at the Philippine General Hospital, following Pacifico’s release from Fort Santiago. Before Ferdinand was supposedly smuggled out of his house wearing a constabulary uniform, Josefa allegedly took care of her son at home.

Notably, Spence wrote that Ferdinand was brought home specifically because it was “the safest since the Japanese had already raided it.” Only Josefa claimed that she had daily enemy callers.

Another set of documents among the Marcos papers collected under the administration of Ferdinand’s successor, Cory Aquino, simultaneously confirms a detail in Josefa’s affidavit while falsifying another.

The documents pertain to Josefa’s attempts to be reimbursed by the U.S. Armed Forces for the P10,000 she gave to Bonoan. Included in her claim was a receipt from “Col. I.J. Willis”—supposedly a code name of Bonoan—dated December 8,1944. By then, Ferdinand had long left his home in Manila to head north where he would join the 14th Infantry of the U.S. Army of the Philippines-Northern Luzon on December 12, 1944, based both on Marcos-approved narratives and more objective sources. How then was Josefa able to engage with guerrillas hiding from the enemy if she was under constant surveillance by the Japanese?

Josefa’s claim for reimbursement was filed in December 1947. Based on her written response to a 1953 claim by the Bureau of Internal Revenue that she owed the state over P100,000 in taxes, she did not get the P10,000.00 back. In the same response to the BIR, Josefa noted that her husband Mariano was a “practicing attorney” until his death, which she dated “February 1944.”

But Ferdinand, in one of the documents included in his submissions for Ang Mga Maharlika’s recognition, stated that “M.M.”—Mariano Marcos—was an active commanding officer in his unit as of July 1944.

However, there is compelling evidence—including an article published in The Tribune in 1943, an immediate post-war report on Ilocos Norte by an Ilocano war hero, the recollection of an American guerrilla commander, and Japanese war diaries—that Mariano was in fact a Japanese collaborator (a propagandist to be exact) executed not by the Japanese as Ferdinand claimed, but by Filipino guerrillas possibly in late 1944 or early 1945.

The historical marker beneath a statue of Ferdinand’s father in the Mariano Marcos State University in Batac, Ilocos Norte states that Mariano died in March 1945.

Pages From the BIR Letter t… by VERA Files

Pages From the BIR Letter to Josefa and Josefa’s Response by VERA Files on Scribd

At least two of Mariano’s siblings also engaged in aiding the Japanese. His sister Antonia, a writer, had at least one piece of pro-Japanese propaganda published in The Tribune. His brother, Pio, was mentioned in the pages of The Tribune as a prominent member of his district’s Neighborhood Association or Tonarigumi, which assisted the Japanese in propaganda distribution and enemy surveillance, among others. Ferdinand, however, would claim that Pio was actually an intelligence officer of the Maharlikas.

THE RANCH THAT NEVER WAS

In the same 1953 communication regarding her taxes, Josefa declared that among her family’s assets before the war was a ranch in Davao, valued at over P1.2 million (about P4.7 billion today). Josefa stated that “the cattle [in the ranch] was registered in the name of [her] son, Ferdinand E. Marcos, because the original animal stock of the ranch was purchased with money left as a legacy for him by his grandparents.” She said that the cattle had been commandeered by the U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East, and that a claim had been filed with the U.S. Court of Claims.

There are indeed records of the claim, the most readily accessible being the decision, Marcos v. United States, granting Ferdinand standing to sue the U.S. government. The doctrine established by that case was later overturned, but even before that, based on a list of judgements of the Court of Claims submitted to the U.S. Senate in January 1957, the Marcos cattle claim was denied in January 1956.

Ferdinand was unable to convince the Court that the Marcos Ranch cattle existed.

Spence would lie about this failure in his book. “During the war,” he wrote, “the Japanese stripped [the ranch]; afterward, veterans squatted on it, and Ferdinand refused to claim it from them.” Spence made no reference to the Court of Claims filing, which was premised on the allegation that American soldiers requisitioned Ferdinand’s cattle.

Through Spence and a foreword to the book titled The Young Marcos by Victor Nituda, Pacifico later claimed that his family was so lacking in funds in the late 1930s—they were spending a lot on legal fees for the defense of Ferdinand and Mariano for the murder of the Marcos patriarch’s political rival, Julio Nalundasan—that he had to stop his medical schooling and become a constabulary officer in Mindanao to make money. Pacifico continued to serve in Sulu until the outbreak of the war. If his older brother was sitting on a million pesos worth of cattle at the time, why did Pacifico need to temporarily quit his studies and earn a salary?

The 1935 Nalundasan assassination figures into the claims of both Ferdinand and Josefa about the ranch. Mariano ran against Nalundasan to be the representative of Ilocos Norte’s second district in 1934 and 1935, then against Ulpiano Azardon in 1936. Mariano lost all those elections, but had to have been a resident of Ilocos Norte to even run. In 1935, Mariano was one of the lawyers of the first person suspected of killing Nalundasan, Nicasio Layaoen, who was acquitted.

In December 1938, Mariano, Ferdinand, Pio, and Ferdinand’s uncle, Quirino Lizardo, were arrested for suspicion of murdering Nalundasan. They would be preoccupied with the case until October 1940, when all three had already been acquitted.

In the three years prior to 1934, Mariano was Deputy Governor-at-Large of Davao where the ranch was supposedly located. The dates of Mariano’s term are stated in a memorandum by Vicente Francisco, defense lawyer of the Marcoses during the Nalundasan trial, which was reproduced in the 1965 book, Was Ferdinand Marcos Responsible for the Death of Nalundasan?

The undivided province of Davao started having elected governors only in 1935. But one affidavit among the files left behind in Malacañang after the Marcoses left which likely offered as evidence in the Court of Claims case states that Mariano was Governor-at-Large of Davao until 1936, and that the importation of cattle happened between 1934 and 1940. The first is clearly false, and the latter extremely unlikely.

Another affidavit states that “all papers [regarding the registration of the Marcos ranch cattle] and other pertinent documents to such registration were lost or destroyed during the war.” All Ferdinand had were affidavits that contained false or unverifiable information.

Although the Marcos ranch was a lie, all other claims about Josefa’s finances were apparently accepted by the BIR. She stated that her net worth actually decreased instead of increased between 1947 and 1953, and that the property she acquired within that time was bought using proceeds from the sale of her assets or from numerous loans. On the other hand, Ferdinand, who was also being hounded by the BIR for paying insufficient taxes, settled his deficiencies after negotiating a significant reduction of what he owed.

Both mother and son may have failed in several attempts to profit from false war claims, but Ferdinand’s election to the presidency—and his retention of power for two decades—ensured that they could at least direct how their family’s wartime activities were chronicled in state-approved narratives.

Within their lifetimes, the Marcoses had public structures named after them. By hook or by crook, they made sure their country would consider them honored heroes.

A MOTHER’S INFLUENCE

Josefa’s notoriety in helping her son with his corrupt practices did not end with war time claims.

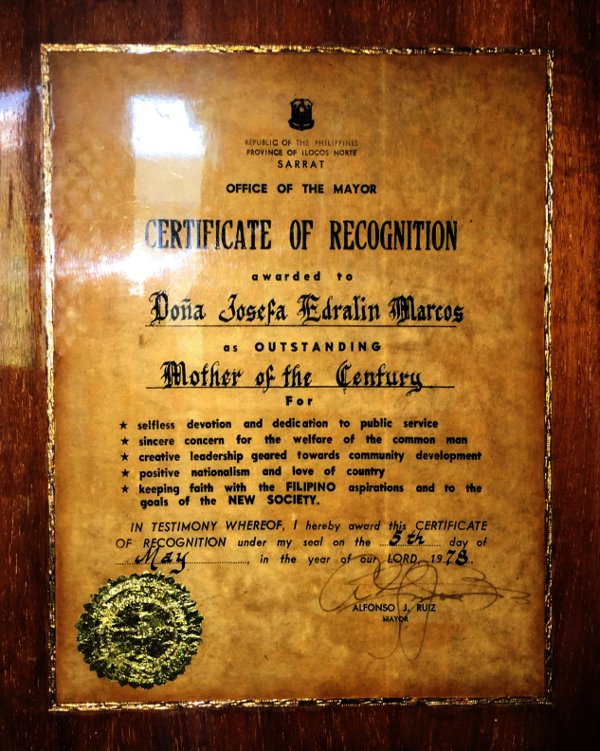

In the heyday of Ferdinand’s dictatorship, according to Ricardo Manapat in Some Are Smarter Than Others: The History of Marcos’ Crony Capitalism, Josefa “was quite active in business corporations and in other money-making ventures which capitalized on her special relationship with her powerful son.” During the ‘70s, she was already in her 80s.

“Doña Josefa,” Manapat continued, “headed the Doña Josefa Edralin Marcos Foundation, which was the financial holding group of the more than a dozen companies where she was chairman of the board. SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) records reveal that she was involved in many areas such as sugar, logging, shipping, and foods, Doña Josefa was helped by a core of close relatives who did the spade-work for her. By making contributions to her foundation, businessmen were able to ask her to intercede with various government officials for favors. All she had to do was to lend her name to corporations so that their business deals would be facilitated.”

An August 5, 1977 declassified cable from the US embassy mentions Josefa as the chair of the board of Intercontinent Minerals and Oil Corporation, “one of several small chromite producers presently trying to ride the crest of high chromite prices and short supply to promote foreign investment in its operations.” It adds that “Doña Josefa is often used in this capacity in the mining industry when marginal projects may benefit from ‘palace influence’.”

As early as 1967, with Ferdinand just in the second year of his first term as president, she started buying real estate in Cape Coral, Florida in the U.S. Josefa, as reported in the March 22, 1986 issue of the News-Press [Fort Myers, Florida], introduced herself as the widow of “a Supreme Court justice” and that her “family was obviously wealthy.” She is supposed to have said that her husband was “killed by a stray bullet when the Japanese fled Manila during the World War II.”

“I will know you by your fruits,”Josefa was quoted as saying in the July 14, 1978 issue of the Singaporean paper, New Nation. “The kind of children you give to the world shows the kind of mother you are.”

That statement, at least, is true — in her case.