Originally published by Vera Files on November 2, 2021.

So how did Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos, Jr. end up in a graduate program in business administration at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania without an undergraduate degree?

On November 25, 1978, Marcos swore in his 21-year-old son as special assistant to the president. In a press release on this, Malacañang stated that Bongbong held a special diploma in social studies from Oxford University.

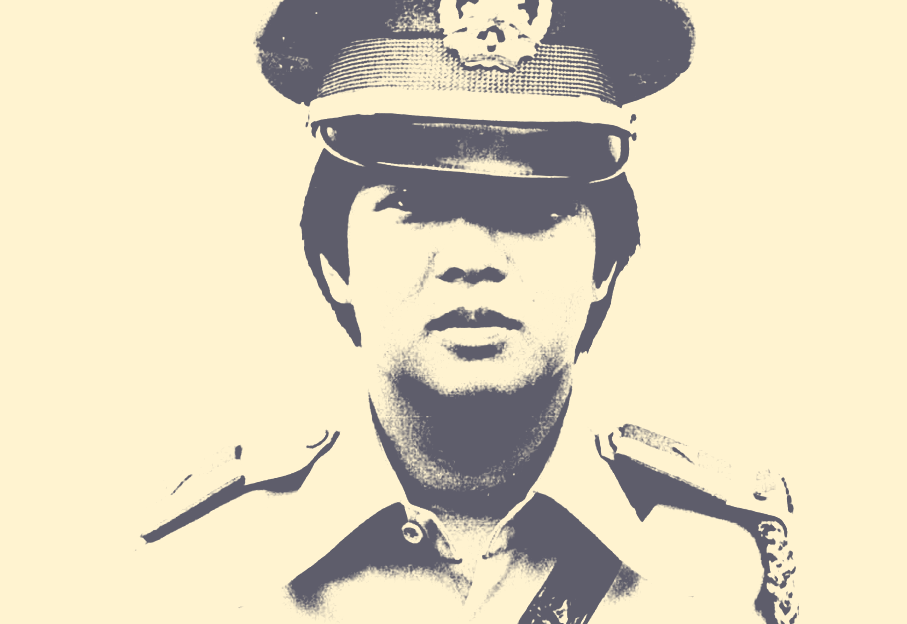

Two months later, Malacañang announced that while undergoing a six-month basic officer’s course at the Philippine Marine Training Center, Bongbong had been commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Philippine Constabulary. But as the Honolulu Advertiser noted, Bongbong “[did] not have to wear a uniform because he was sworn in last [November] as one of the president’s special assistants and will be detailed to the presidential palace.” A US Department of State cable noted that Bongbong “[had] been elected president of his officers’ class” and that a columnist “noted tongue-in-cheek that this class is now sure to produce a high percentage of generals.”

The papers left behind when the Marcoses fled Malacañang in 1986 describe the extent of the family’s efforts to ensure that Bongbong was accommodated in one of the most prestigious business schools in the United States, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

On January 27, 1979, Marcos received a confidential personal letter from Francis Ablan, then an executive of Caltex (Philippines), Inc., conveying a cable from Frank Zingaro, a vice president of the multinational oil giant Caltex Petroleum Corp. and once president of the Philippine-American Chamber of Commerce of New York. Both had personal ties to the Marcoses.

Ablan wrote that Zingaro “[had] some good connections with people of Wharton School of Business and with some other graduate schools of business. He also offered that if it is your desire, we can send Bongbong’s application through him and he will personally handle the submission of same to the right offices/people. By the way, Frank reminded me that his assistance is purely a personal matter between you and him. He welcomes the opportunity of being of help in return for the many courtesies extended to him during his visits with you and the First Lady.”

In his cable dated January 25, 1979, Zingaro explained to Ablan the admission process at Wharton and Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. He wrote that “Arjay Miller currently dean of the Stanford Business School and formerly once president of Ford Motor Company has been advised of applicant’s impending application submission and we’re hopefully confident he will use his good offices to assist.”

But then he hedged: “I must remind you that admissions committees of graduate schools and more particularly Stanford and Wharton are an unusual breed and they take pride in their independence to make evaluations of candidates without outside pressures or without regard to the applicant’s social or political status.”

Photo 3 1979 01 25 Privatel… by VERA Files

After initially considering Stanford, a decision seemed to have been made by May 1979 that Bongbong would attend Wharton instead. On May 3 that year, Jose A. Syjuco Jr., deputy chief of mission of the Philippine embassy in London, sent a telex to Malacañang to inform Bongbong that he must “rush Wharton forms to Ernie Pineda [Ernesto C. Pineda, Philippine consul general in New York] soonest. He will make [a] strong attempt to push it through but he needs the basic application.”

Photo 4 1979 05 03 Syjuco t… by VERA Files

With all the diplomatic efforts and muscle-flexing of business executives, it remains unclear how Bongbong got into Wharton without an undergraduate degree, extensive work experience, or what persuasive arguments Marcos presented that the school gave credit to. Bongbong would later give various reasons for why he was unable to finish his studies at Wharton.

And then there was the lie, of course, that he did complete the program.

Bongbong started at Wharton on or about August 10, 1979, which means that he was accepted by the prestigious business school within three months after two Philippine diplomats offered to “push through” his application. This is based on a Department of State cable dated August 7, 1979 stating that the young Marcos was to arrive in Philadelphia “to begin a two-year course of study at the Wharton School of Business” and that the state department had known about his study plans “for some time.”

The cable also noted that Marcos’ son, “with appropriate bodyguards,” had been earlier “accredited by the Philippine Mission to the United Nations as its ‘military advisor’ with the rank of attaché, with an assistant who also carries the rank of attaché.” The people who drafted the communication for the undersigned, US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, noted that the ‘nominal U.N. assignment is presumably intended to give Bong Bong diplomatic immunity while he is in [the U.S.]’.”

Why he needed to have diplomatic immunity and bodyguards who stayed with him in a house in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, is unclear. Bongbong, as Ferdinand Marcos II, continued to be listed as an attaché of the Philippine U.N. Mission in 1980, based on that year’s edition of Permanent Missions to the United Nations: Officers Entitled to Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities.

How did the “military advisor”—fresh out of months-long training— perform in Wharton?

Bongbong himself has provided a means for evaluating this. On his official website, a copy of his Wharton MBA transcript issued on April 2, 2015 is posted showing that the presidential aspirant in next year’s elections enrolled for four terms between the fall 1979 and 1981. He did not enroll for the 1981 spring term.

Looking at a course description of Wharton MBA program in the mid-1980s and Bongbong’s transcript, it appears that in the fall term of 1979, he failed to earn credit for a core subject: administration. He performed a bit better during the spring 1980 term, passing all the courses taken by Wharton MBA students regardless of their major. Of the five courses he took during the fall 1980 term, he earned credit in only two.

Bongbong did not pass any of the courses during the fall 1981 term; he received two incompletes, suggesting that he attended classes but failed to submit all prerequisites to earn course credit. Overall, he earned eleven credit units before withdrawing from the program. He was far from finishing his MBA; he retook administration in the fall 1981 term, but received a mark of NR (not reported) for the course. The transcript states that his major is “undeclared.”

It would have been necessary for him to declare a major and complete major courses before he could write a thesis or do a capstone/advanced study project. Yet in several biographic notes and at least one interview, Bongbong claimed that he was already writing his MBA thesis or dissertation when he had to cut his studies short because he was elected vice governor of Ilocos Norte.

Marcos Jr. was elected vice governor of Ilocos Norte not in 1981, as many online profiles of him claim, but on January 30, 1980 at the age of 22. Batas Pambansa Blg. 52, enacted on December 22, 1979, lowered the minimum age for governors and vice governors from 23 to 21. In fact, based on an Agence France Presse article dated December 20, 1979, Bongbong was originally being pushed to run for governor. His aunt, Elizabeth Marcos Roca, who had held the Ilocos Norte governorship since 1967, even stated that she was willing to give way to her nephew. But the article noted that Bongbong was “not enthusiastic about making politics a career.”

According to an article published in the Honolulu Advertiser on January 4, 1980, Bongbong had “told a crowd of well-wishers (in the Philippines) that he planned to complete his studies leading to a master’s degree in business administration in the United States.” Even with his election assured, he maintained that his focus was on his studies.

Bongbong ran uncontested and became vice governor of Ilocos Norte after the January 30, 1980 elections while still a student at Wharton. The foreign media reported that so as not to interrupt his studies, Bongbong chose to be sworn into office at the Philippine embassy in Washington D.C. on February 28, 1980. Eduardo Z. Romualdez, Bongbong’s uncle and then Philippine ambassador to the U.S., administered his oath.

Indeed, it seems that throughout 1980, or several months after he was sworn in as vice governor, Bongbong remained in the U.S. His transcript reflects that he continued to take classes. As reported by international media, such as the Ohio-based New Herald and Kyodo News, in November 1980, Marcos asked the U.S. government to give Bongbong additional protection because of purported threats to his life. The New Herald article noted that Bongbong was “an attache to the Philippine delegation to the United Nations in New York.” Marcos himself eventually beefed up security for his son in the U.S.

There is ample written, photographic, and audiovisual evidence that Bongbong was in the Philippines during the April 7, 1981 constitutional plebiscite, the June 16, 1981 presidential election, and the third inauguration of his father as president on June 30, 1981. This period coincided with the time he did not enroll in Wharton.

There is evidence though that he returned to the US in the fall of 1981 to attend classes again. But it seemed that besides attending classes, Bongbong was attending to other business as well. A November 25, 1982 article in The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that in 1981, a state trooper stopped Bongbong for driving over the speed limit at the New Jersey Turnpike. The article said, “The state trooper who pulled over the young Marcos, a student at the University of Pennsylvania, was startled to see a semi-automatic rifle at the backseat and a revolver strapped to the leg of a young woman in the passenger seat.”

Bongbong flashed a diplomatic passport and was let go. “Except,” the article concluded, “the State Department said, that young Marcos was not registered as a diplomatic agent of his country.”

Thus, for Bongbong and his people to say that he discontinued his studies solely because he was elected vice governor—a position that, based on Batas Pambansa Blg. 51, practically only required him to serve as the governor’s substitute or spare tire, the latter function that he would fulfill in a few years—is, to put it charitably, inaccurate.

THE LIES

On March 24, 1983, Bongbong assumed the governorship of Ilocos Norte after his aunt resigned for health reasons. It was around this time that lies about his university education were carried by the local press. The Religious of the Good Shepherd, Philippines-Japan, in an October 27, 2021 Facebook page post, showed a March 25, 1983 news clipping from an unidentified newspaper announcing that Bongbong was the new Ilocos Norte governor. The news item claimed that Bongbong “is a graduate of Oxford University in London, where he earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in politics, philosophy, and economics. He later attended the Wharton School of Finance in Pennsylvania.”

On March 31, 1983, a member of the Religious of the Good Shepherd wrote Oxford about what she read in the news report. A month later, on April 20, the university wrote back to her with a definite answer.

“Ferdinand Martin Romualdez matriculated in 1975 at St. Edmund Hall, University of Oxford, to read Politics, Philosophy and Economics. He did not however complete his Preliminary examinations, and is not therefore a graduate of this University. It follows that he does not hold any degree. He was however awarded a Special Diploma in Social Studies in 1978.” The emphasis was in the original.

After getting exiled in Hawaii with his family in 1986 as a result of the People Power revolt, Bongbong returned to the Philippines in 1991 and was elected as representative of Ilocos Norte’s second congressional district from 1992 to 1995.

In the featured profile in the 1993 Congressional Highlights Quarterly Report, Bongbong’s educational background not only indicated that he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in PPE, it also stated that he obtained a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Pennsylvania.

On February 24, 2015, Marites Danguilan Vitug writing for Rappler, once again raised the question of how truthful Bongbong was regarding his university education. A senator since 2010, Bongbong posted his resume in his official senate page indicating that he had a Bachelor of Arts degree in PPE political and a master’s degree in business administration from the Wharton School of Business. Vitug’s article belied Bongbong’s claims.

In a statement released in response to Vitug’s piece, Bongbong maintained that his academic records were “accurate,” that he “got a diploma” from Oxford but did not finish his studies in Wharton because he was elected vice governor of Ilocos Norte.

In an ambush interview on March 2, 2015, a reporter asked Bongbong if he had a degree. He replied, “I suppose. I got a diploma, kaya nga may diploma ako e.” This which is reminiscent of his sister Imee’s “sa pagkakaalam ko, nag graduate ako” (as far as I know, I graduated). Imee Marcos, now senator, also made false claims of having graduated from Princeton University, the University of the Philippines College of Law, and the Asian Institute of Management.

In the same interview, Bongbong admitted that he did not finish his MBA in Wharton, saying “I was writing my dissertation. I never got to. . . Pinauwi na ako e (I was asked to come home).” This was a reiteration of claims about his achievements at Wharton—which do not conform with his transcript—that can be found as early as the 2009 version of his official website and written profiles or recorded interviewee introductions that drew from such sources.

On October 28, 2015, he was asked once more about his academic degrees. In his interview with Julius Babao, Karen Davila, and Ces Drilon on ABS-CBN’s Bandila, he definitively claimed that he received a bachelor of arts degree from Oxford. Pressed by Davila that official records showed that what he got was a special diploma, Bongbong insisted that, “Yes, but it is still a bachelor of arts degree.”

In another interview on January 21, 2016, in a DZMM program, Marcos claimed that the certification he obtained from Oxford University in 2015 states, “This is to certify that Ferdinand Marcos has completed a BA degree in social sciences.” He further said that he transferred from PPE to politics, and that is the college degree he completed.

In response to the more recent questions about Bongbong’s education, his spokesperson Vic Rodriguez said on October 23, 2021 that Bongbong has “always been forthright” about his academic records.

This is akin to Imelda vouching for her son.

Cecilio T. Arillo, in his 2012 book Imelda: Mothering and Poetic and Creative Ideas in a Troubled World asked the former first lady, “Will Bongbong pursue the vision of his father?” Imelda replied, “He’s committed to that. Humbly speaking, his leadership qualities, his intellectual and managerial skills and moral and ethical upbringing, I am confident he will not fail. Bongbong was educated at Oxford University, England in 1978 with AB Political Science, Philosophy and Economics, and at Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, USA with a Master’s in Business Administration.”

His father, the dictator, lied about his son’s degree. His mother, the undead half of the conjugal dictatorship, flaunted the same lie. And the son, who now wants to be president, continues the lie. For the past 43 years, the Filipino people have been lied to.