Originally published by Vera Files on March 11, 2020.

The story of the two First Quarter Storm protests that ended with violent dispersals in January 1970 has been told repeatedly across five decades.

One particular narrative on the First Quarter Storm has achieved canonical status: Jose F. Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage. In that book, four students who died during the January 30 Battle of Mendiola are named: Feliciano (actually Felicisimo) Roldan of Far Eastern University, Ricardo Alcantara of the University of the Philippines, Fernando Catabay of Manuel Luis Quezon University, and Bernardo Tausa of Mapa High School.

Lacaba did not mention whether the protesters carried any type of firearms. They did not, according to findings released on March 12, 1970 by the Senate Special Committee that investigated the violent January rallies.

“Not a single firearm has been claimed to have been discovered on a demonstrator. How then justify the military’s resort to firepower, aimed at first upward but later directly at the ground a few feet before the crowd?,” the committee said.

Juan Ponce Enrile, who was in Malacanang at that time in his capacity as Secretary of the Department of Justice, stated in his 2012 memoir that claims that some of the demonstrators had Garand rifles—hardly concealable weapons—were “not verified.” Nelson Navarro, who edited Enrile’s memoir, said in his own autobiographical book that the protesters on that fateful night—himself included—had “crudely and hastily made sticks and pillboxes” as “the most serious weapons in [their] arsenal.”

Marcos always claimed the contrary. In his January 31, 1970 diary entry, he said “the rioters were sniping at the MPD, Metrocom& soldiers with .22’s.” The 1971 book Today’s Revolution: Democracy, ghostwritten for Marcos by writer-bureaucrat Adrian Cristobal, noted an “exchange of gunfire”between demonstrators and palace defenders.

Brig. Gen. Raval, the Philippine Constabulary chief who reportedly asked for Marcos’ permission to fire during the Battle of Mendiola (Marcos repeatedly said that he only gave permission to fire water hoses), was more conspiratorial than his commander-in-chief. On February 4, 1970, Raval was quoted by the Manila Times as stating that he had seen a worldwide pattern of “demonstrators killing some of their members to dramatize it and gain public sympathy,” and he was certain the gunshots did not come from his men.

His “false flag” insinuation drew widespread condemnation, even from then Armed Forces Chief of Staff Gen. Manuel Yan.

Raval tendered his resignation a few days after making such statements. In his February 6, 1970 diary entry, Marcos said that he had asked Raval to resign, though he found him to be “one of the most loyal of the officers in the Armed Forces.”

Raval was not among officers Marcos commended in his broadcast address to the nation on January 31, 1970. This, despite Enrile’s account that Raval was the only general to immediately respond to Marcos’s call for reinforcements.

The Senate Special Committee found that it was the arrival of such reinforcements—which increased the number of troops guarding Malacañang to almost 800—that re-agitated protesters who had already started to mellow down.

Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr., Marcos’s chief critic, lambasted the president for his praise of his military men. In a February 2, 1970 speech in the Senate, Aquino asked: “What has he done to bring the murderers of Alcantara, Catabay, Roldan and Tausa to justice? Instead of trying to locate them, he has paid tribute to their killers—and the Commander of the Metrocom, Colonel Ordoñez, has been promoted to General!”

Raval’s relief was the closest approximation of a law enforcer suffering as a consequence of the January 30 deaths.

As he had immediately decided, sans evidence, that the siege was a full-on attempt to forcibly wrest power from him and the demonstrators were armed for assault—all later countered by investigations, foreign observers, and recollections of Enrile and Gen. Ileto—Marcos may not have been particularly interested to know who among his men fired the fatal shots.

In fact, according to the Manila Bulletin, on February 1, 1970, Marcos, accompanied by his wife and children, met with the January 30 palace troops in Malacañang Park. He praised the “exemplary conduct of the soldiers …in successfully repelling, without firing a shot, the riotous students who tried to force their way into the Malacañang grounds.”

He contradicted himself in his January 30, 1970 diary entry: “I hear shooting and I am told that the MPD have been firing in the air.” It was just one of his several contradictory and unverified claims about the Battle of Mendiola.

It seems Marcos was severely rattled by the siege. Dozens of armed soldiers surrounded Malacañang days after the battle. But even the presence of his own army at the palace did not give Marcos comfort. In its April 25, 1970 editorial, the Philippines Free Press gave the reason why: “His mortal fear in that January 30 incident was not so much that the masses of students would succeed in storming and destroying the Palace as that the troops guarding the Palace would turn around and stage a coup.”

Money for Maulings, Cash for Corpses

In their February 2-3,1970 issues, newspapers in the Philippines and abroad noted that in the immediate aftermath of the January 30 Battle of Mendiola, Marcos had publicized setting up a fund for student activities. It was such a transparent attempt to appease student activists with money that even the CIA, in its April 3, 1970 memorandum, noted that “Marcos has tried to buy off and redirect the students rather than acknowledge and deal with their grievances.”

Expectedly, the radical left scoffed at the fund. Ang Bayan, the official organ of the Jose Maria Sison-chaired Communist Party of the Philippines, called it “one face of the counter-revolutionary dual tactic of the fascist regime to soften up their struggle against the reactionary state.”

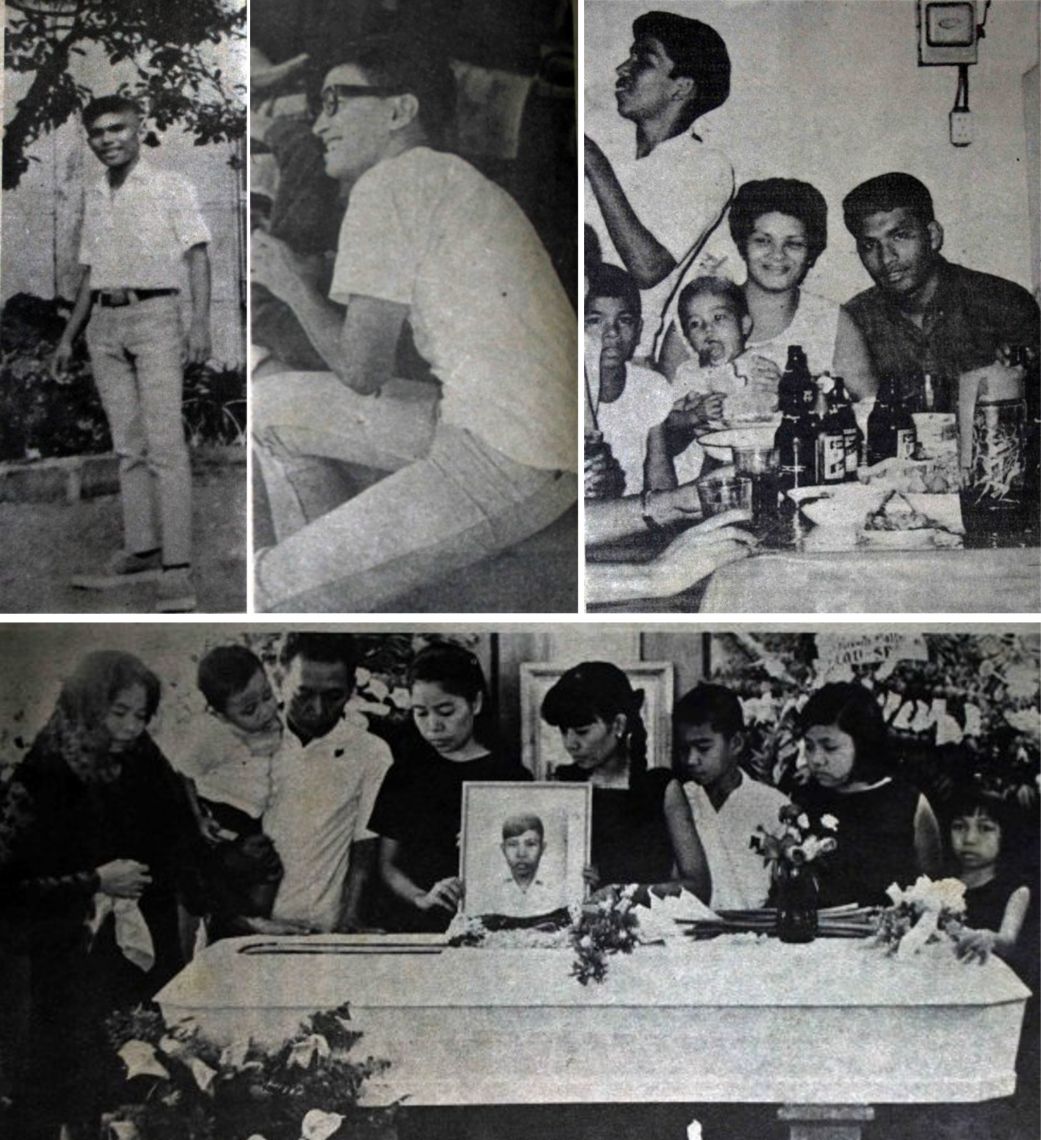

The first four fatalities of the January 30, 1970 Battle of Mendiola. Top photos (left to right): Bernardo Tausa, Ricardo Alcantara, Felicisimo Singh Roldan; bottom photo: Fernando Catabay. From Mercedes A. B. Tira’s “The Mourning of Protest,” Graphic Magazine, February 18, 1970, 10-11.

Marcos also publicly supported directly compensating heirs of those who died during the battle. On 30 September 1971, he signed into law Republic Act 6399. Its full title reads: “An Act Appropriating Ninety Thousand Pesos as Compensation to the Heirs of Mass Demonstration Victims Ricardo Alcantara, Fernando Catabay, Felicisimo S. Roldan, Bernardo Bausa, Jesus Mejia and Leopoldo Inelda, All Deceased, and Authorizing the Appropriation of Five Hundred Thousand Pesos as Compensation for Deaths and Injuries Sustained in a Public Demonstration, Rally, Protest March, Assembly or Mass Action.”

Six victims were named, although commemorations—especially those led by leftists—usually mention only four. Mejia and Inelda also died from gunshot wounds sustained during the Battle of Mendiola, but they perished a few days later. Newspaper reports referred to them as bystanders.

RA 6399 stated the fund was to be administered by the Department of Social Welfare, suggesting it was a form of assistance, not judicial settlement. A Malacañang press release said Marcos signed the law in the palace in the presence of the heirs of the victims.

While the bipartisan bill was being shepherded toward legislation, scores were injured or killed in protests throughout the country. Among them were Enrique Sta. Brigida, who was beaten to death by law enforcers during the March 3, 1970 “People’s March” in Manila, and Francis Sontillano, who died when a pillbox exploded over his head nearFeati University during a student demonstration on December 4, 1970.

In addition, the bombing of the Liberal Party election rally in Plaza Miranda left nine dead and nearly a hundred injured on August 21, 1971.

Apparently, some were able to make claims against the P500,000 fund. But in 1977, five years into his martial law dictatorship, Marcos declared a number of appropriations dormant and reverted them to the General Fund. Among them, the P272,000 balance of the demonstration victim fund. Thus, RA 6399 became a dead law.

However, after 1977, there were numerous other casualties in mass protests dispersed by law enforcers using lethal weapons. The dead include: two at the February 1981 rally of farmers in Guinayangan, Quezon; four at the “Daet Massacre” in Camarines Norte in June 1981; five at the December 1981 demonstration in Culasi, Antique; and 22 at the Escalante Massacre of September 20, 1985. At least three protests in Manila after 1977 also ended with fatalities. Among them was a second “Mendiola Massacre” in September 1983, where seven protesters, two firemen and a soldier died.

National Day of Sorrow protest rally in 1983 in Mendiola that turned bloody.

Neither Marcos—who retained legislative power up to his last days as president—nor the Interim/Regular Batasang Pambansa ever appropriate additional funds for deaths and injuries in public protests up to the time Marcos was deposed in 1986.

The most significant law related to such activities was the Public Assembly Act of 1985, which punishes law enforcers who carry firearms within a hundred meters of a public assembly or unnecessarily fire their guns to disperse such gatherings.

But by then, the blood of protesters was already on the hands of security forces who had time and again, over a period of 20 years, dispersed rallies with gunfire with nary an effect on their freedom, finances, or careers.

A total of P318,000 was given to families of those killed or injured in demonstrations during the Marcos regime. Whether justice was given to those victims—and to those who never received a centavo from the government—is another matter.